This article was originally published in The Fielding Bible, Volume 1.

We are well aware that we are not the first statistical analysts to question Derek Jeter’s defense at shortstop. Others before us have argued that Jeter was not a good shortstop, and yet he has won the Gold Glove the last couple of years, the Yankees certainly have won several baseball games with Jeter at short, and he is among the biggest stars in baseball.

Asked about Derek Jeter’s defense on a radio show in New York one year ago, I answered as honestly as I could: I don’t know. I know that there are Yankee fans and network TV analysts who believe that he is a brilliant defensive shortstop; I know that there are statistical analysts who think he’s an awful shortstop. I don’t know what the truth is. You’ve seen him more than I have; you know more about it than I do.

I am instinctively skeptical. I don’t tend to believe what the experts tell me, just because they are experts; I don’t tend to believe what the statistical analysts tell me, just because they are statistical analysts. I take a perverse pride in being the last person to be convinced that Pete Rose bet on baseball, and I fully intend to be the last person to be convinced that Barry Bonds uses Rogaine. I am willing to listen, I am willing to be convinced, but I want to see the evidence.

So John Dewan brought me the printouts from his defensive analysis, and he explained what he had done. John’s henchmen at Baseball Info Solutions had watched video from every major league game, and had recorded every ball off the bat by the direction in which it was hit (the vector) the type of hit (groundball, flyball, line-drive, popup, mob hit, etc.) and by how hard the ball was hit (softly hit, medium, hard hit). Given every vector and every type of hit, they assigned a percentage probability that the ball would result in an out, and then they had analyzed the outcomes to determine who was best at turning hit balls into outs. One of their conclusions was that Derek Jeter was probably the least effective defensive player in the major leagues, at any position.

So I said, “Well, maybe, but how do I know? How do I know this isn’t just some glitch in the analysis that we don’t understand yet?”

“I knew you would say that,” said John. “So I brought this DVD.” The DVD contained video of 80 defensive plays:”

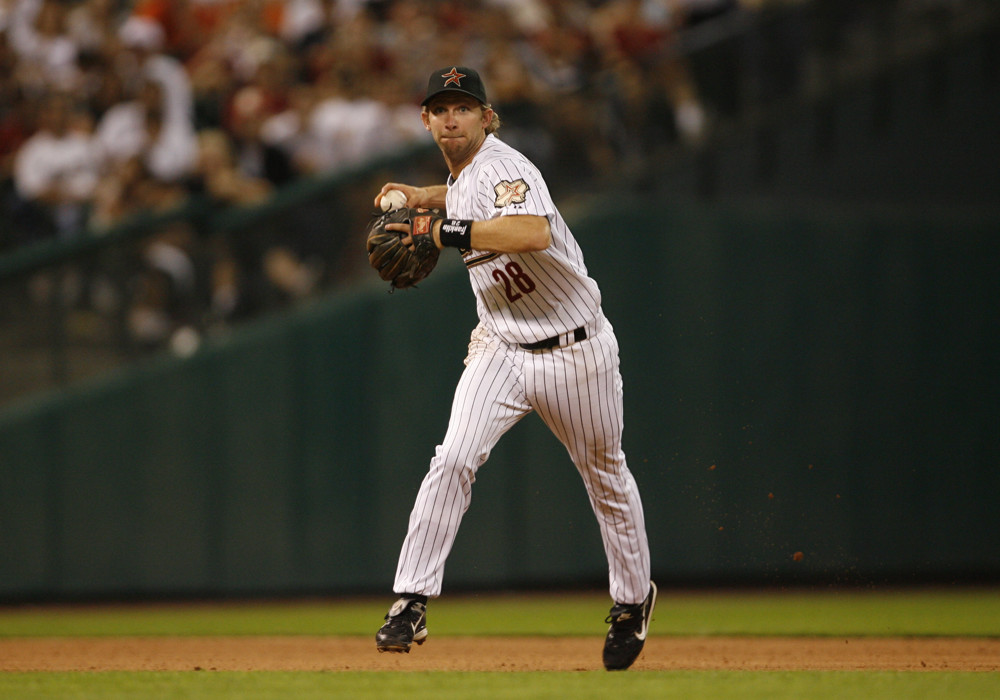

The 20 best defensive plays made by Derek Jeter.

The 20 worst defensive plays of Derek Jeter, not including errors.

The 20 best defensive plays of Adam Everett, who the analysis had concluded was the best shortstop in baseball.

The 20 worst plays of Adam Everett, not including errors.

How do we define “best” and “worst”? It’s up to the computer. Every play is entered into the computer at Baseball Info Solutions. The computer then computes the totals, and decides that a softly hit groundball on Vector 17 is converted into an out by the shortstop only 26% of the time. Therefore, if, on this occasion, the shortstop converts a slowly hit ball on Vector 17 into an out, that’s a heck of a play, and it scores at +.74. The credit for the play made, 1.00, minus the expectation that it should be made, which is 0.26. If the play isn’t made—by anybody—it’s -.26 for the shortstop.

The best plays are the plays made by shortstops on balls on which shortstops hardly ever make plays, and the worst plays are No Plays made on balls grounded right at the shortstop at medium speed. Sometimes these actually don’t look like bad plays when you watch them. Sometimes the ball takes a little bit of a high hop and Ichiro is running, and he beats the play on something the computer thinks should be a routine out—but it’s still a legitimate analysis, because the shortstop didn’t have to play Ichiro that deep. He could have pulled in two steps; he could have charged the ball. He weighed the risks, he used his best judgment, and he lost. That happens.

Anyway, this business of looking at Derek Jeter’s 20 best and 20 worst plays and Adam

Everett’s.. .logically, this would appear to be an ineffective way to see the difference between the two of them. Suppose that you took the video of A-Rod’s 20 best at-bats of the season, and his 20 worst, and then you took the video of Casey Blake’s 20 best at-bats of the season, and his worst. The video of A-Rod’s 20 best at-bats would show him getting 20 extra-base hits in game situations, and the 20 worst would show him striking out or grounding into double plays 20 times in game situations. The video for Casey Blake would show Casey Blake doing exactly the same things. This isn’t designed to reveal the differences between them; this is designed to make them look the same.

That being said, watching Derek Jeter make 40 defensive plays and then watching Adam Everett make 40 defensive plays at the same position is sort of like watching video of Barbara Bush dancing at the White House, and then watching Demi Moore dancing in Striptease. The two men could not possibly be more different in the style and manner in which they run the office. Jeter, in 40 plays, had maybe three plays in which he threw with his feet set. He threw on the run about 20-25 times; he jumped and threw about 10-15 times, he threw from his knees once. He threw from a stable position only when the ball, by the way it was hit, pinned him back on his heels.

Everett set his feet with almost unbelievable quickness and reliability, and threw off of his back foot on almost every play, good or bad. Jeter played much, much more shallow than Everett, cheated to his left more, and shifted his position from left to right much, much more than Everett did (with the exception of three plays on which Everett was shifted over behind second in a Ted Williams shift. Jeter had none of those.)

Jeter gambled constantly on forceouts, leading to good plays when he beat the runner, bad plays when he didn’t. Everett gambled on a forceout only a couple of times, taking the out at first base unless the forceout was a safe play.

Many or most of the good plays made by Jeter were plays made in the infield grass, slow rollers that could easily have died in the infield, but plays on which Jeter, playing shallow and charging the ball aggressively, was able to get the man at first. These were plays that would have been infield hits with most shortstops, and which almost certainly would have been infield hits with Adam Everett at short.

For Everett, those type of plays were the bad plays, the plays he failed to make. The good plays for Everett were mostly hard hit groundballs in the hole or behind second base, on which Everett, playing deep and firing rockets, was able to make an out. These, conversely, were the bad plays for Jeter—hard-hit or not-too-hard-hit groundballs fairly near the shortstop’s home base which Jeter, playing shallow and often positioning himself near second, was unable to convert. And there was literally not one play in the collection of his 20 best plays in which Jeter planted his feet in the outfield grass and threw. There were only three plays in the 40 in which Jeter made the play from the outfield grass, two of those were forceouts at third base, and all three of them occurred just inches into the outfield grass.

Now, I want to stress this: I don’t know anything about playing shortstop. I don’t have any idea whether the shortstop should play shallow or deep, when he should gamble and when he should play it safe, how he should make a throw or whether it is smart for him to shift left and right in playing the hitters. The professional players know these kind of things; I don’t.

That’s not what I’m saying. I’m not suggesting that Jeter is a bad shortstop because he plays shallow and throws on the run and gambles on forceouts and shifts his position. What I am saying is this: that watching that video, it was very, very easy to believe that, if Adam Everett was on one end of a spectrum of shortstops, Derek Jeter was going to be on the other end of it. But that video is in no way, shape or form the basis on which we argue that Derek Jeter is not a successful shortstop.

OK then, what is that basis?

First of all, there is the summary of Jeter’s plays made and plays not made. Both Jeter and Everett had plays that they made on the types of balls a shortstop does not usually make a play on, and both Jeter and Everett had plays they didn’t make on balls a shortstop should make the play on. But, as in the case of A-Rod and Casey Blake at the bat, the numbers are quite a bit different.

Adam Everett had 41 No Plays in 2005 on which, given the vector, velocity and type of play, the expectation that the shortstop would make the play was greater than or equal to 50%. Derek Jeter had 93 such plays. 93 plays you would expect the shortstop to make, Jeter didn’t make—52 more than Everett.

On the other side of the ledger, Derek Jeter had 19 plays that he did make that one would NOT expect a shortstop to make (less than 50% probability). Adam Everett had 59. Calling these, colloquially, Plus Plays and Missed Plays:

|

Plus Plays |

Missed Plays |

| Derek Jeter |

19 |

93 |

| Adam Everett |

59 |

41 |

Brief accounting problem. . .Our charts show Adam Everett as being 73 plays better (on groundballs) than Derek Jeter—+34 as opposed to -39. The totals here are 92 plays (40 + 52). Why the difference?

The 93 plays that Jeter missed were not plays on which there was a 100% expectation that the shortstop would make a play. Some of them were plays on which there was a 55% expectation the shortstop would make a play; some of them were 95%. He probably should have made about 75% of them, so the 52-play difference between them on those plays leads to something more like a 40-play separation in the data.

The low defensive rating for Derek Jeter is not based on computers, it is not based on statistics, and it is not based on math. It is based on a specific observation that there are balls going through the shortstop hole against the Yankees that might very well have been fielded. Lots of them—93 of them last year, not counting the ones that might have gone through when somebody else was playing short for the Yankees. Yes, there are computers between the original observation and the conclusion; we use computers to summarize our observations, and we do state the summary as a statistic. But, at its base, it is simply a highly organized and systematic observation based on watching the games very carefully and taking notes about what happens.

Jeter, given the balls he was challenged with, had an expectation of recording 439 groundball outs. He actually recorded 400. He missed by 39. Everett, given the balls hit to him, had an expectation of 340 groundball outs. He actually recorded 374. He over-achieved by 33-point-something.

This is an analysis of groundballs. Shortstops also have to field balls hit in the air—not as many of them, but they still have to field them. That part of the analysis helps Jeter a little bit. Jeter is +5 on balls hit in the air; Everett is -1. That cuts the difference between them from 72 plays to 66.

Could these observations be wrong? It’s hard to see how, but. . .I’m a skeptic; I’m always looking for ways we could be wrong.

This is not the only basis for our conclusion; actually, this is one of four. Another way of looking at this problem is to make a count of the number of hits, and where those hits land on the field.

Against the Yankees last year there were 196 hits that went up the middle, over the pitcher’s mound, over second base and into center field for a hit (more or less. . .near second, and some of them may have been knocked down behind second base by the second baseman, the shortstop, or a passing streaker). That is the most common place where hits go, and an average team gives up 177 hits to that hole. Against Houston, there were 169—27 fewer than against the Pinstripers.

Against the Yankees in 2005 there were 131 hits in the hole between third and short, as opposed to a major league average of 115. Against the Astros, there were 83.

Against the Yankees in 2005 there were 110 hits that fell into short left field, over the shortstop but in front of Hideki Matsui. The major league average is 106. Against the Astros, there were 94.

The Yankees did have an advantage vs. the average team in terms of infield hits allowed; they allowed 85, whereas the average team allowed 89. (The Astros, 79.) But taking all four of the holes which are guarded in part by the shortstop, the Yankees allowed 35 hits more than an average major league team, and 97 more than the Astros.

|

Yanks |

Average |

Astros |

| Infield Hits |

85 |

89 |

79 |

| Up the Middle |

196 |

177 |

169 |

| In the SS/3B Hole |

131 |

115 |

83 |

| In short left |

110 |

106 |

94 |

| Totals |

522 |

487 |

425 |

So there is a separate method, relying on a different set of facts, which gives us essentially the same conclusion: that Everett is an outstanding shortstop, and Jeter not so much.

There is a third method, Relative Range Factor, which is explained in a different article. Relative Range Factor is an entirely different method, relying not on Baseball Info Solutions’ careful and systematic original observation of the games, but on a thorough and detailed analysis of the traditional fielding statistics. It’s just plays made per nine innings in the field, but with adjustments put in for the strikeout and groundball tendencies of the team, the left/right bias of the pitching staff, and whether the player was surrounded by good fielders who took plays away from him or bad fielders who stretched out the innings and created more opportunities. That method is explained on page 199.

In that article, the Relative Range Factor article, I scrupulously avoided any mention of Derek Jeter, which turned out to be more difficult than you might expect. In 2005, Jeter’s Relative Range Factor actually is OK. . .it’s middle-of-the-pack, not really noteworthy. But the Relative Range Factor is not a precise method; there is some bounce in it from year to year. I believe it is more than accurate enough in one year to make it highly reliable over a period of three years, but it is probably not highly reliable in one year.

Jeter’s “OK” performance in Relative Range Factor in 2005 is an aberration in his career. It was only the second time in his career that his Relative Range Factor hasn’t been absolutely horrible. In fact, although I haven’t figured enough Relative Range Factors yet to say for certain, I will be absolutely astonished if there is any other shortstop in major league history whose Relative Range Factors are anywhere near as bad as Jeter’s. I’ll be amazed.

In one part of that article, to illustrate the method, I wanted to contrast Ozzie Smith with some player who would be easily recognized and generally understood by modern readers to be a not-very-good defensive shortstop. I started with a list of team assists by shortstops relative to expectation. . .several of Ozzie’s seasons were near the top end of the list, and I chose one, and then I went to the bottom of the list to try to find a “bad example.”

I was looking for modern seasons, because I wanted modern readers to recognize the player, and I was looking for teams that had shortstops you might remember. Of course, 80% of the teams at the bottom of the list were 25 years ago or more, and most of the other “classically bad” shortstops were guys who were just regulars for one year, so people wouldn’t necessarily remember them.

Eventually I found the player I needed—Wilfredo Cordero in 1995. Everybody remembers Wilfredo; everybody knows he wasn’t much of a shortstop. I found him after walking past six separate seasons of Derek Jeter. While virtually no other recognizable name at shortstop had had even one season in which his team had 40 fewer assists by shortstops than expected, Jeter had season after season after season in that category.

We have, then, a third independent method which confirms that Jeter’s range, in terms of his ability to get to a groundball, is substantially below average. All three methods suggest essentially the same shortfall. We have one more method.

Our fourth method is zone ratings. The concept of zone ratings was invented by John Dewan—the primary author of this book—in the 1980s. Over the years zone ratings have proliferated, some of them better than others. The zone ratings presented here are not exactly the same as the originals. They’re better. . .better thought out, better designed, with access to better accounts of the game.

Zone ratings and the plus/minus system are actually very similar concepts. . .what the zone rating actually is is a simpler and less precise statement of the same original observations that make up the fielding plus/minus. What we do in zone ratings is, we take the data from each of the 262 vectors into which the field is divided, and we identify those at which the shortstop records an out more than 50% of the time. Those are the shortstop’s “responsible vectors”. . .the vectors for which he is held accountable. The zone rating is a percentage of all the plays the shortstop makes in those vectors for which he is accountable.

Derek Jeter’s zone rating is .792, and he made 26 plays outside his zone. Adam Everett’s zone rating .860, and he made 78 plays outside his zone.

We can’t really count this as a fourth indicator that Derek Jeter’s range is limited, because the underlying data is redundant of our first indicator, the +/- system (-39 for Jeter, +33 for Everett). Still, setting that aside, we have three independent systems evaluating Jeter’s defense (as well as the defense of every other major league shortstop). One system—Relative Range Factor—looks at traditional fielding stats, which is to say it looks at outs made. One system looks at where hits landed, which is to say it looks at hits. One system looks at balls in play, and evaluates the fielder by the rate at which balls in play are divided between outs and hits.

All three systems agree that Jeter has extremely limited range in terms of getting to groundballs—and all three systems provide essentially the same statement of the cost of that limitation. It is very, very difficult for me to understand how all three systems can be reaching the same conclusion, unless that conclusion is true. It’s sort of like if you have a videotape of the suspect holding up a bank and shooting the clerk, and you have his fingerprints on the murder weapon, and you recover items taken in the robbery from his garage. Maybe the videotape is not clear; it could be somebody who looks a lot like him. Maybe there is some other explanation for his fingerprints on the murder weapon. Maybe there is some other explanation for the bags of money in his garage. It is REALLY difficult to accept that there is some other explanation for all three.

Those Yankee fans with a one-switch mind will demand to know, “How come we won 95 games, then? If Derek Jeter is such a lousy shortstop, how is it that we were able to win all of these games?”

But first, no one is saying that Derek Jeter is a lousy player. Let’s assume that the difference between Derek Jeter and Adam Everett is 72 plays on defense. That’s huge, obviously; that’s not a little thing that you blow off lightly. But almost all of those 72 plays are singles. What’s the value of a single, in runs? It’s a little less than half a run. 72 plays have a value of 30, 35 runs.

That’s huge—but it is still less than the difference between them as hitters. Derek Jeter is still a better player than Adam Everett, even if Everett is 72 plays better than Jeter as a shortstop. (Jeter created about 105 runs in 2005; Everett, 61.)

In one way of looking at it, it makes intuitive sense that Derek Jeter could be the worst defensive shortstop of all time. Unusual weaknesses in sports can only survive in the presence of unusual strengths. I don’t know who was the worst free throw shooter in NBA history—but I’ll guarantee you, whoever he was, he could play. If he couldn’t play, he wouldn’t have been given a chance to miss all those free throws. If a player is simply bad, he is quickly driven out of the game. To be the worst defensive shortstop ever, the player would have to have unusual strengths in other areas, which Jeter certainly has. It would help if he were surrounded by teammates who also have unusual strengths, which Jeter certainly is. The worst defensive shortstop in baseball history would have to be someone like Jeter who is unusually good at other aspects of the game.

Second, we have not exhausted the issue of defense. There are other elements of defense which could still be considered—turning the double play, and helping out other fielders, and defending against base advancement, I suppose. The defensive ratings that we have produced, while they are derived from meticulous research, might still be subject to park illusions, to influences of playing on different types of teams, and from influences by teammates. There is still a vast amount of research that needs to be done about fielding.

But at the same time, I have to say that the case for Jeter as a Gold Glove quality shortstop is a dead argument in my mind. There is a lot we don’t know, and Derek Jeter could be a better shortstop than we have measured him as being for any of a dozen reasons. He is not a Gold Glove quality shortstop. He isn’t an average defensive shortstop. Giving him every possible break on the unknowns, he is still going to emerge as a below average defensive shortstop.