The Wild Card Round is upon us, and perhaps the only team you were able to keep up with religiously during the season was your own. A lot goes on in the NFL every week, and you’ve likely caught some glimpses at other teams here and there, maybe during island games, but might not have as good a grasp on the other 31 teams as you do your own.

That’s where this scheme primer comes in. Here, we’ll be providing you with a brief crash course on the offenses of the Wild Card Round teams, packed with advanced tendency stats and football terms you may want to use to flex on your friends in the group chat this weekend. Without further ado, let’s get started.

AFC

#2 Seed Buffalo Bills

The Bills do some interesting stuff on offense. They put their running backs in motion more than any team but the Dolphins, and their backs have the second-highest ADoT of any team in the league. They get their backs out into the pattern at a high rate, but they’ll get them into corner routes and seams rather than just out into the flats or over the ball, which is symptomatic of a passing game that is generally downfield-oriented with high horizontal stretches (e.g. double post) and outside vertical stretches.

They are zone-run heavy (like most teams), which are well-suited to James Cook’s skillset, but they have moving parts gap schemes to supplement it, and will, needless to say, use Josh Allen on designed runs out of these looks.

Lastly, they rank sixth in both RPO and screen rate, which is their form of quick game because they rank 24th in traditional short dropbacks.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: The Bills’ put their running backs in motion the second-most of any team and have the second-highest ADOT.

#3 Seed Baltimore Ravens

This is the bullyball team of the AFC. Two-thirds of the Ravens’ offensive snaps are played in heavy personnel groupings, and they rank last in 11 personnel usage.

They run well no matter the design, ranking in the top five in success rate in both gap and zone schemes. Lamar Jackson obviously makes this easier. Teams have tried stacking the box (second-highest rate in the league) but the Ravens rank first in stacked box run success rate.

The juice in the passing game comes from intermediate and deep concepts, with Jackson having the second-highest ADoT in the NFL and 30% of his throws targeting verticals, post, corners, and crossers. As a result, he’s the quarterback with the highest Boom Rate in the NFL (plays gaining an expected point or more).

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: Two-thirds of the Ravens offensive snaps are in heavy personnel

#4 Seed Houston Texans

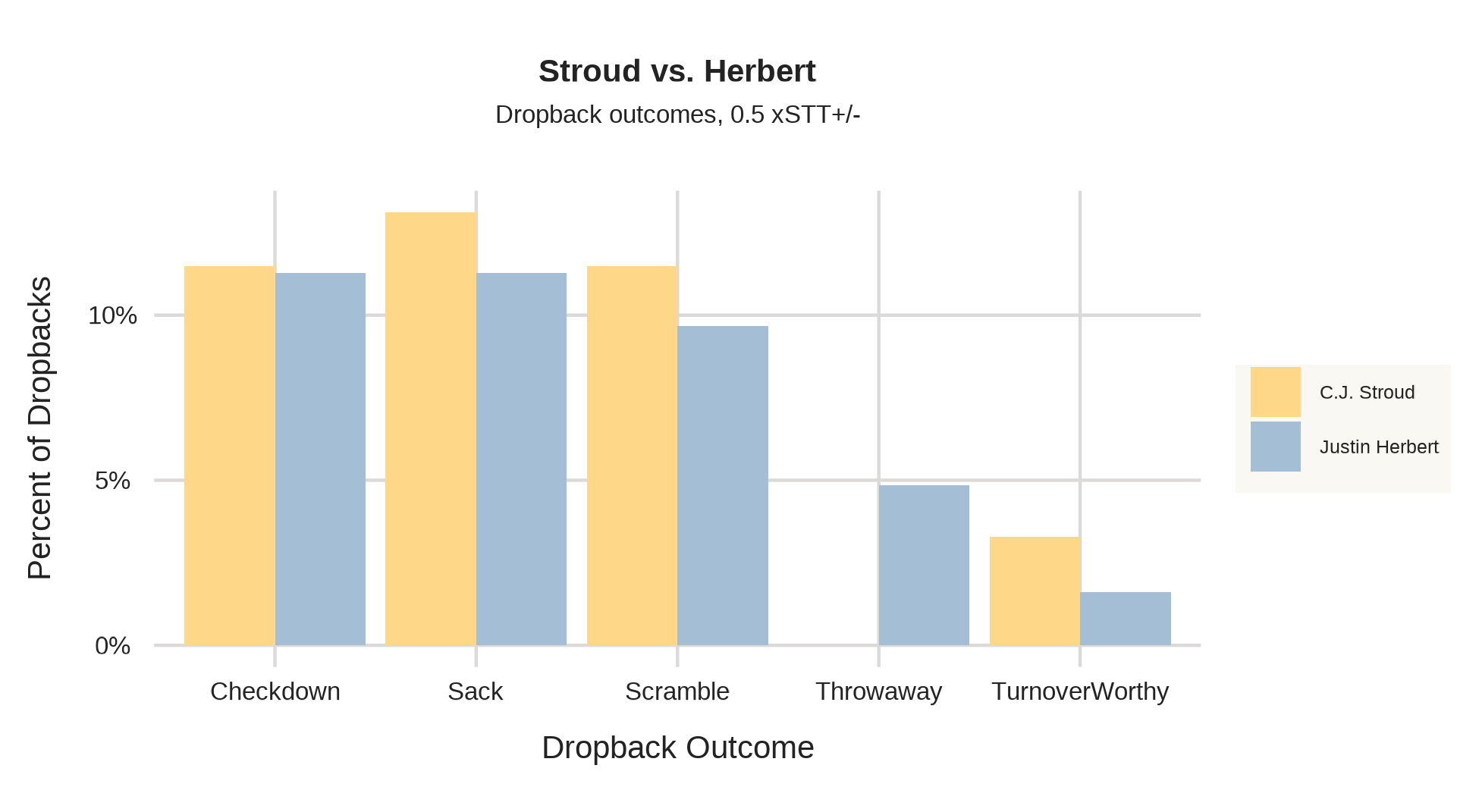

The Texans’ offense has used condensed formations more than any other team in the NFL this year (about 27 plays per game). They don’t make great use of the space this affords, with C.J. Stroud throwing out-breakers at the third-highest rate and about twice as often as crossers.

These condensed formations also tend to draw more defenders into the box and contribute, in part, to the top ten rate at which they run into a loaded box. Furthermore, they typically don’t do it very well, ranking sixth-worst in success rate on such carries.

Like other Shanahan offenses tend to be, they’re a zone-heavy team and use a lot of motion, but unlike other Shanahan offenses, they disproportionately use motion to pass and run at the fifth-lowest rate in the league on plays with motion.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: The Texans use condensed formations more than any other team.

#5 Seed Los Angeles Chargers

The arrival of Jim Harbaugh has brought old school football to Los Angeles. This is a gap-scheme, play action-heavy offense that orients itself around power and counter runs and play action shot plays; the Chargers rank 1st in play action rate, 5th in gap run rate, and Justin Herbert is tied for second in ADoT (8.7).

With an interior offensive line that ranks 24th in run blocking Total Points, the Chargers haven’t fully grown into their new identity, ranking 24th in rushing success on gap concepts. They’re largely reliant on the play action game to push the ball downfield, ranking 3rd in net passing EPA with play action and 16th without.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: The Chargers rank 1st in play action rate.

#6 Seed Pittsburgh Steelers

The Russell Wilson offense is the same as ever, and the Steelers’ offense is built around the go-ball. Wilson threw verticals at the 2nd-highest rate in the NFL this year, and outs and flats at the 3rd-highest rate. In fact, half of non-screen attempts by Wilson have targeted a vertical or something relatively short and outbreaking.

Considering Wilson averages a paltry 0.02 EPA/attempt against Cover 3 and that the Steelers are a bottom five team in rushing success against stacked boxes, the key to playing them seems to be stacking the box and playing Cover 3. Let them run boot Flood and check it down to the flat for 5 yards every play, who cares.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: Russell Wilson threw verticals at the 2nd-highest rate in the NFL this year, and outs and flats at the 3rd-highest rate.

#7 Seed Denver Broncos

This is a training wheels offense that relies heavily on screens and boots/sprintouts, ranking 4th and 1st in the NFL in those categories, respectively. Furthermore, they rank dead-last in quick game usage – which makes sense considering Bo Nix wasn’t particularly adept at that in college.

This is a static—last in motion rate—point-and-shoot operation that’s overreliant on screens and scrambles to move the ball in the passing game. They’ve generated 28 EPA on scrambles and screens, which is higher than the EPA they’ve netted across all pass plays (23.6).

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: The Broncos rank 4th in screen usage and 1st in boot/sprintout usage.

NFC

#2 Seed Philadelphia Eagles

The Eagles used more 2×2 formations than anyone in the NFL this year and are more generally motored by West Coast staples which create low, horizontal stretches in zones (think double slants and slant-flat) and triangle reads (like snag), RPOs, and AJ Brown iso concepts.

Their run game is a little zone-heavy but is mostly Saquon-heavy. They haven’t benefitted from Jalen Hurts’ legs like they have in the past; he hasn’t averaged a meaningfully positive EPA per attempt on designed non-sneak runs since 2022. This unit is powered more by its personnel at the skill positions than anything else.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: The Eagles used more 2 x 2 formations than any team in the NFL in 2024.

#3 Seed Tampa Bay Buccaneers

The Buccaneers generated the second-most EPA and the most yardage on screen plays of any team in the SIS database (2015-present). They just generally like to throw near the perimeter, with lots of concepts that feature outbreakers like two-man stick, smash variants, and flood, generally with in-breakers coming into Baker Mayfield’s vision from the other side late in the down.

In the running game, they’re the most efficient gap scheme team in the NFL, which was not on anyone’s bingo card headed into the year. They were 27th last season.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: The Buccaneers generated the most yardage and second-most EPA on screens of any team in the last 10 seasons.

#4 Seed Los Angeles Rams

The Rams don’t look a whole lot different than they have throughout the Stafford era. They’re still running a lot of zone, motion, and play action, and they’re still under center a lot.

The passing game has a lot of high low concepts, outside vertical stretches, and crossing patterns, but their receiving corps doesn’t have a legitimate speed element and they’ve struggled mightily against man coverage this year. They rank 28th in success rate against man coverage, but 1st against zone coverage.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: The Rams crush it against zone coverage (highest success rate), but rank 28th vs man.

#5 Seed Minnesota Vikings

The Vikings are a zone-heavy run team that likes to operate from under center (31st in shotgun usage. However, unlike the Chargers they aren’t aggressive in their pursuit of play action from under center.

The passing game operates in the intermediate-to-deep area of the field, with 54% of Darnold’s passes landing somewhere between 5 and 20 yards downfield, the 3rd-highest rate in the league. Darnold’s 8.7 ADoT is tied with the previously-mentioned Jackson and Herbert.

They work the ball to the outside and over the middle in relatively equal measure, with Darnold hunting crossing routes at one of the higher rates in the league.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: 54% of Sam Darnold’s passes go 5 to 20 yards downfield, the 3rd-highest rate in the league.

#6 Seed Washington Commanders

The upstart Commanders are notable for their varied and successful run game. They’re the most efficient zone running team in the league, but they are 5th-lowest in usage. They are 6th in gap run rate, but their success on such concepts has waned down the stretch.

They’re one of the teams that’s tapped into 3×1 gun strong and setting the back to the tight end in 3x1Y formations, ranking third in the usage of such formations to create unbalanced defensive structures.

The core passing game is pretty standard Air Raid fare like Y Cross and Stick variants, but to supplement that they’ve just generally tapped into some of the more common ‘cheat codes’ and rank 4th in both RPO and play action rate, and 10th in screen rate.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: The Commanders are the most efficient zone running team in the league, but have the 5th-lowest usage rate.

#7 Seed Green Bay Packers

The Packers’ offense is interesting because this is largely an offense that stretches you horizontally and creates a lot of conflict with fast motion, but they don’t really run a lot of true quick game. Their ‘quick game’ is being 2nd in RPO rate and screen rate.

The quarterback is a big play hunter though, and so this is all spiced up with a dose of shot plays whenever LaFleur needs to appease Jordan Love’s urge to launch the ball.

In the run game, they’re a zone-heavy team but rank top 8 in both zone and gap success rate.

They line up in 11 personnel most often (as most teams do), but they’re much more balanced out of it than most teams. They led the league with a 41% run rate.

Re’stat’ing for emphasis: The Packers rank 2nd in RPO rate and screen rate.