This article was adapted from our presentation at the 2025 Saberseminar conference in Chicago. We are one of the sponsors of the event, and we highly recommend you check it out if you’re interested in baseball analytics!

Many of you are aware of our catch-all defensive metric, Defensive Runs Saved. One piece of that is our measure of a catcher’s ability to steal strikes, which we call Strike Zone Runs Saved.

It’s been a little over 10 years since we put it out, so we wanted to take some time to look back at some notable players, umpires, and teams within the context of Strike Zone Runs Saved. We also want to talk about how much the environment has changed in the time since, and what we’re thinking about the metric now.

Where to find Strike Zone Runs Saved

If you can find Defensive Runs Saved, you can find Strike Zone Runs Saved, since it’s one of the many components in that overarching metric.

But if you’re looking for that piece specifically, you can find it in any of these spots:

Background

The ability for catchers to steal strikes based on how they receive a pitch became a topic du jour around the turn of the 2010’s. Catcher framing metrics were ascribing 50+ runs per season to the best framers relative to the average, in part because this was a skill that hadn’t been rigorously examined previously.

Around that time, we at SIS set out to create a metric that not only measured the catcher’s responsibility for a called strike, but everyone involved in the interaction: the umpire, batter, and pitcher as well.

In 2014 we announced that metric, Strike Zone Runs Saved, to our clients, and in 2015 we presented that research at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference. That paper shared the event’s research award that year.

How the metric works

At its core, Strike Zone Runs Saved (SZRS) takes the various called balls and strikes in a season and splits responsibility for them between the four people involved: catcher, umpire, pitcher, and batter.

The core calculation is based on how often strikes are called above/below a calculated expectation, which is based on four factors:

- Pitch location

- Ball/Strike count

- Batter handedness

- Proximity of the pitch to the catcher’s target (specifically in the left/right direction)

For each pitch, we give credit for a called strike or ball depending on how likely it was to have been called a strike to begin with.

For example, a given pitch might be assessed at a 60% expected strike rate given the factors we consider.

If called a strike we’d attribute 100 – 60 = 40% of a strike across everyone.

If called a ball we’d attribute 0 – 60 = -60% of a strike across everyone.

Iterative approach

The metric follows an approach similar to Jeff Sagarin’s team ratings that have been around for quite a while. The core idea is that we don’t know directly how much of an impact each player/umpire has, but we can observe through a full season of pitches what those people tend to do. From there, we can run the same calculation again with an adjusted assumption, and then our estimates will get a little better. And we can keep doing that until there no longer is much to learn from this process.

First iteration

To start, each pitch is treated like the above, where we have an expected called strike rate and we take a plus-minus approach to determine how much credit to apportion.

In the example above, a called strike with a 60% expected strike rate which would result in +40% of a strike of credit, the value would be split 10-10-10-10 between the four actors involved.

We do that for every pitch, which results in a measured Extra Strikes Per Pitch (ESPP) for each person over the course of the full season.

Subsequent iterations

For every following iteration, we re-run the same set of pitches, but we adjust the calculation to use the ESPP from the previous iteration.

In that same example, we originally had 40% of a strike of credit to go around. We now subtract out any additional (or reduced) expected called strike rate based on the ESPP of the pitcher, catcher, batter, and umpire involved. If that total was, say, +5%, we’d now have 40 – 5 = 35% credit to go around, and that would now get split evenly among the four actors.

Then that value gets added to each actor’s ESPP from the previous iteration.

At the end of each iteration, we check to see if the values are changing much. At a certain point things start to converge on a single set of ratings, and that’s when we stop.

The result is a value in terms of extra strikes per pitch for each person, which we can then multiply by a computed run value (how many runs it is worth to change a ball to a strike) to get Strike Zone Runs Saved.

Notables through the years

Here are some of the leaders and trailers over the 15 full seasons since we started collecting this data.

Catchers

Total Runs Saved Leaders

| Yasmani Grandal |

87 |

| Tyler Flowers |

85 |

| Jonathan Lucroy |

80 |

| Russell Martin |

72 |

| Buster Posey |

71 |

Runs Saved per Season Leaders (minimum 5 seasons)

| Jose Molina |

8.4 |

| Tyler Flowers |

7.7 |

| Russell Martin |

7.2 |

| Yasmani Grandal |

6.7 |

| Miguel Montero |

6.6 |

Jose Molina, one of the standard bearers of catcher framing value, played only 5 years in this sample, but he made those years count. Yasmani Grandal didn’t have quite that per-season performance, but he has the benefit of having more years of his career in this sample.

Tyler Flowers is one of those players who people know the name of because of our ability to measure this skill, and you can see why. We talked about it with him for an article a couple years ago, when Defensive Runs Saved turned 20.

When it comes to guys like Buster Posey who are in the Hall of Fame conversation, ~7 wins of framing value makes a big impact for a player who didn’t play into his mid-to-late thirties.

Umpires

Pitcher-friendliest Umpires, SZRS per season

| Doug Eddings |

11.5 |

| Bill Miller |

11.0 |

| Tim Welke |

7.4 |

| Bob Davidson |

7.2 |

| Phil Cuzzi |

5.4 |

Hitter-friendliest Umpires, SZRS per season

| Paul Schrieber |

-8.0 |

| Alfonso Marquez |

-6.3 |

| Edwin Moscoso |

-6.2 |

| Carlos Torres |

-5.2 |

| Gerry Davis |

-5.2 |

You can see that the per-season scale for an umpire isn’t so different from a catcher.

Doug Eddings and Bill Miller have and have had the most pitcher-friendly strike zones in baseball. They’ve largely gone unchanged over the years, and that consistency puts them quite noticeably above the others.

At the opposite end of things are the umpires with the most hitter-friendly zones. Paul Schrieber’s career only partly overlapped with this stat, but he stands out on a per-year basis. Alfonso Márquez has been known for years to have a smaller strike zone than most of his peers. But the most hitter-friendly umpires don’t stand out quite so much as the large-zone guys.

One other note about Eddings, Miller, and Márquez is that though these numbers indicate they favor either the pitcher or hitter more than any other umpires, this does not seem to have impacted how they are viewed by the MLB office. They each been given prominent postseason assignments the last few years, including the last two World Series.

Batters

Pitcher-friendliest Batters, SZRS per season

| Xander Bogaerts |

1.1 |

| Curtis Granderson |

1.0 |

| Alcides Escober |

0.9 |

| Hunter Pence |

0.9 |

| Luis Garcia Jr. |

0.8 |

Hitter-friendliest Batters, SZRS per season

| Dustin Pedroia |

-1.7 |

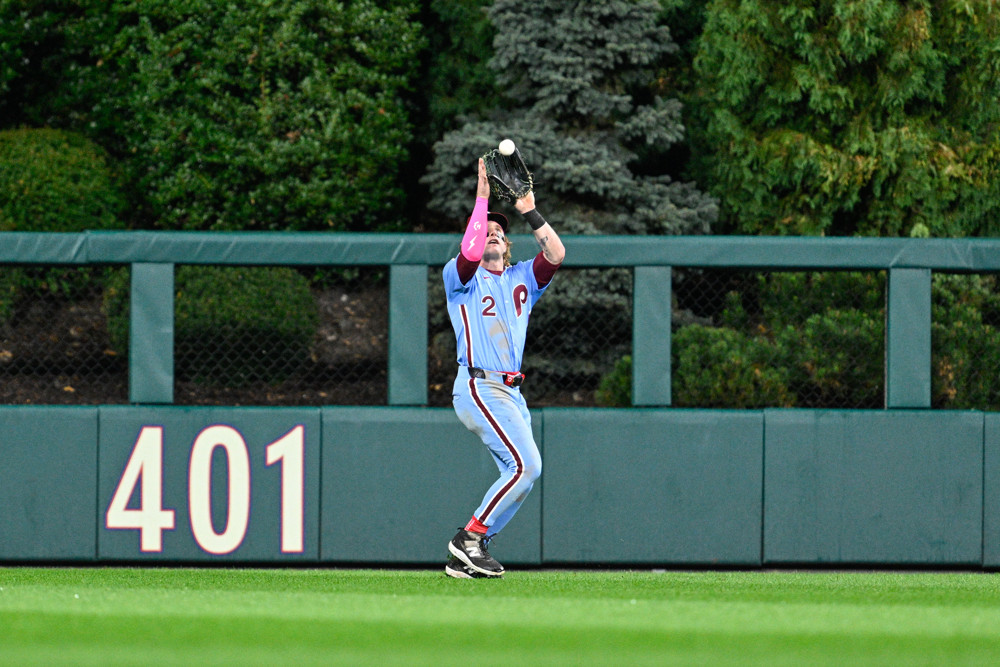

| Rhys Hoskins |

-1.5 |

| Carlos Santana |

-1.4 |

| Ryan McMahon |

-1.3 |

| Yadier Molina |

-1.3 |

Here’s where Strike Zone Runs Saved gets more interesting, because we start talking about players that aren’t part of the typical framing conversation.

The scale for batters isn’t mind-blowing, just a run per season at the extremes. And that’s not shocking, considering there isn’t some obvious direct mechanism by which the batter might influence a strike call, other than maybe how close he stands to the plate.

But if we take a little bit of a step back, we start to find some signal.

Looking at the top 20 names on each list, less than half of the pitcher-friendly category were above average by wRC+ in that timespan. All but one player from the hitter-friendly category was an above average hitter. So there appears to be some kind of reputation effect at play.

Additionally, 6 of the top 30 players in terms of getting hitter-friendly calls were themselves catchers.

You often hear about catchers not wanting to get into a tiff with an umpire when they’re batting because they want to get good calls as a catcher, but they seem to get a little bit of favoritism regardless.

Pitchers

Pitcher-friendliest Pitchers, SZRS per season

| Kyle Lohse |

1.7 |

| Ryan Vogelsong |

1.7 |

| Hiroki Kuroda |

1.4 |

| R.A. Dickey |

1.2 |

| Jon Lester |

1.1 |

Hitter-friendliest Pitchers, SZRS per season

| Framber Valdez |

-1.4 |

| Zack Wheeler |

-1.3 |

| Justin Masterson |

-1.0 |

| Anibal Sanchez |

-0.9 |

| Yusei Kikuchi |

-0.9 |

In terms of pitchers, we see a similar scale to that of hitters.

R.A. Dickey’s presence on either end of this spectrum would not have surprised anyone. The knuckleball giveth and taketh away in terms of how catchers and umpires handle it, but in his case it might have giveth just a bit more. We’re accounting for the extent to which the catcher had to adjust to catch the pitch, which would have been the obvious mechanism by which Dickey might have gotten a raw deal.

That Framber Valdez and Zack Wheeler are still succeeding in spite of having arguably the least pitcher-friendly strike zone is illustrative of their success with ground balls and missed swings, respectively.

Otherwise, we’re not sure what to make of these lists. There’s some indication that current pitchers might be getting a little less credit. The calculation of Strike Zone Runs Saved uses a rolling two-year window, so slight changes to rules are accounted for, but it isn’t going to move immediately when guidelines change.

Teams

We looked at teams two ways:

- How well do they produce homegrown catcher framing talent?

- Do catchers they acquire from other teams improve their framing upon arriving?

(Both of the below tables are in terms of Runs Saved per 1,400 innings, about a full season.)

Best teams at producing homegrown catchers

| Brewers |

18.2 runs, 4 players |

| Angels |

9.6 runs, 10 players |

| Giants |

8.9 runs, 8 players |

| Mets |

7.9 runs, 8 players |

| Mariners |

7.6 runs, 8 players |

Best teams at improving the framing of acquisitions

(using a two-year average before and after to smooth out small sample defense stuff)

| Brewers |

14.3 runs, 5 players |

| DBacks |

7.3 runs, 8 players |

| Padres |

5.4 runs, 5 players |

| Braves |

1.2 runs, 8 players |

Bringing up a successful player from your system might just be about the player’s talent, and we have a hard time teasing out those elements.

The Brewers could have been a great example of that, with Jonathan Lucroy’s early career dominance carrying them. However, they’re still at the top of the acquisitions leaderboard thanks to the success of Victor Caratini, Omar Narvaez, and William Contreras after they entered the organization.

We should also give credit to the Angels, who had strong production with more homegrown catchers (10 compared to 8 for any other leader).

Over this span three teams set themselves apart in how much improvement their acquisitions showed. Players acquired by the Brewers, Diamondbacks, and Padres over this decade averaged improving by at least 5 runs saved per full season.

The Rangers have clearly devalued this skill within their organization, because they ranked last for their acquisitions and third-to-last for their homegrown players.

Current work

Command Charting via Computer Vision

For over a decade we’ve had a product called Command Charting, which involves our scouts plotting the catcher’s target for the pitch. The goal is to measure how well a pitcher hits that target. This data has the secondary benefit of being used for Strike Zone Runs Saved, because called strike rate is modulated by how much the catcher had to adjust to receive the pitch.

Over the last couple years we have used Computer Vision technology to expand this product to lower levels of play (minors and college). The model is trained using our manually-charted pitch locations off broadcast video, with a predicted catcher location and confidence intervals. Sufficiently-confident catcher target positions make it into our downstream data pipelines.

This expansion of our toolkit allows us to build a version of Strike Zone Runs Saved in lower levels that doesn’t have to compromise by leaving out some elements of the calculation.

Minor League Strike Zone Runs Saved

Right now we’re testing out the minor league version of Strike Zone Runs Saved with catcher charting incorporated.

The key thing to validate first is whether the distance to the catcher’s target changes the expected strike rate for a pitch.

What we can see here is that, similar to the major leagues, missing the target in the horizontal direction has a meaningful impact on called strike rate, especially when it comes to big misses or dead-on hits. This effect is less extreme than we observe for the majors, but the directionality is the same.

Strike rate vs. average, by target miss quartile:

| Vertical |

Horizontal |

| Closest: +0.4% |

Closest: +1.4% |

| Close: -0.1% |

Close: -0.1% |

| Far: -0.1% |

Far: -0.7% |

| Farthest: -0.4% |

Farthest: -2.7% |

Adding in a seam-shifted two-seam to push righties off the plate would be nice as well. Perhaps even a traditional sinker, even if of poor quality, could help moderate the four-seam usage a bit.

Adding in a seam-shifted two-seam to push righties off the plate would be nice as well. Perhaps even a traditional sinker, even if of poor quality, could help moderate the four-seam usage a bit.