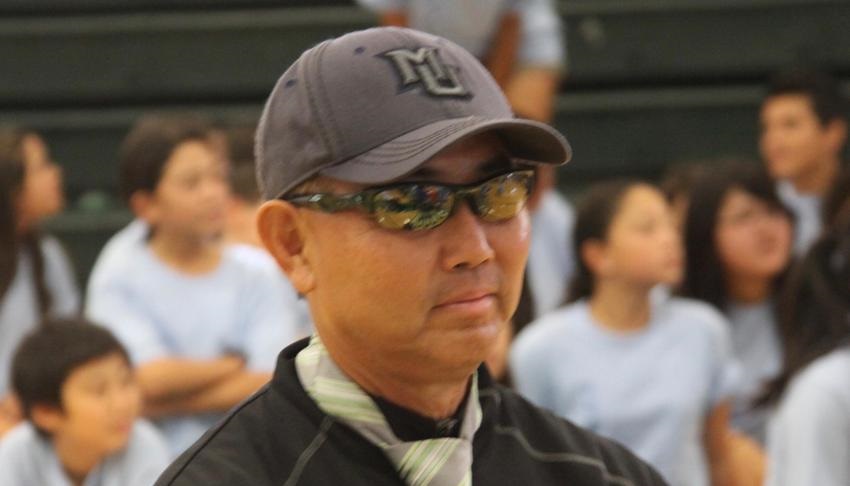

This is the second in a series of interviews with people from different backgrounds who teach defense at different levels from scholastic to college to the pros. Our previous interview with Hawaii high school coaching legend Dunn Muramaru can be found here.

Darren Fenster is the minor league infield coordinator for the Red Sox. He’s previously been the team’s minor league outfield and baserunning coordinator and a minor league manager, as well as a coach for the 2020 Olympic baseball team.

Darren’s passion is teaching baseball to people of all ages – his Twitter handle is @CoachYourKids. In this interview, Darren talks about teaching principles of defensive excellence.

Mark: What does defensive excellence mean to you?

Darren: The short answer is the ability to change a game with your glove. Obviously, you could go down into some different depths of that, but when you talk about excellence, I think that’s the ultimate. Being an elite defender is your ability to change a game defensively with your glove.

And I think that looks a little bit different for infielders as it might for outfielders. I’m the infield coordinator for the Red Sox now, but I was the outfield coordinator the previous three years.

Understanding infield allowed me to look at outfield in a completely different light and then understanding different parts of outfield really kind of shifted a lot of my belief system when it came back to doing a lot of the stuff on the infield side. So for both, when you’re talking about elite defenders, I think your foundation is, are you reliable?

Do you make the routine play routinely? No matter how many highlight-reel plays you make, if you can’t be relied upon to make that routine play every single time, then I don’t think you can be considered an elite defender. I don’t think that it’s defensive excellence if the foundation isn’t there for an infielder.

There is an intellect aspect of defensive excellence. You combine those two in good decisions. Are they in the area where they’re throwing the ball to the right base? Are they fearless in not being afraid to make a challenging play? Others may not be comfortable even thinking about—let alone trying to make—a challenging play.

You think about like a guy like Nolan Arenado and the things that he’s able to do at third base. He’s a complete game changer. And he makes so many different plays in so many ways. And part of that is, obviously, he’s very talented, but there’s some athleticism there and there’s some instinct there that allows him to do some things that a lot of guys won’t even try and he’s the best defensive third baseman of this generation.

I think on the infield side that there’s also obviously an athleticism aspect. So I think the infield is more cerebral, in addition to all of those fundamental physical skills.

And then on the outfield side, I just think about an elite defender as being someone who’s just flying all over the place making plays that most guys don’t make, like Jackie Bradley Jr. or Kevin Kiermaier. On our minor league side, there’s Ceddanne Rafaela (in Double-A) who is cut from that same cloth, where he’s doing things in the outfield you don’t teach.

You look up and they’re already running full speed. They get incredible jumps. They have the instinct for the breaks and for the routes and all those sorts of things. And they just cover a ton of ground, and they turn that 50-50 play into outs more than those drop for hits. They’re able to shut down the extra base whether it be by just sheer effort of getting on the ball as quick as they can by being able to be athletic with their feet and be able to be accurate with their arms. For me, that’s the epitome of outfield play.

Mark: How do you integrate everything you just talked about into teaching kids how to play defense?

Darren: It starts with the fundamentals.

Andy Fox was our infield coordinator prior to his jumping on the big-league staff this year. And I remember my very first year with the organization in 2012, one of the first days of spring training, Andy grabbed 10 of our infielders.

He was just doing these very simple hand rolls that guys were not missing. And it was just so easy.

I asked Andy if we could give them more challenging reps than what we’re doing right now. And he said absolutely. But this is the foundational stuff that we need to get ingrained into guys’ systems so that they have the good habits for when we do have the more challenging types of reps and the more challenging types of plays, they have a foundation from which to build off.

Those fundamental reps were complete game-changers in terms of being able to help make guys fundamentally sound, and I was completely hooked on the importance of foundational reps that allow you to focus on something as simple as glove angle, where you’re turning your glove into the biggest area for the ball to go in.

I use the expression, ‘We don’t catch raindrops.’ If you think about how you would catch a raindrop, that’s what we would call a flat glove versus if your fingers were down. There’s way more area for the ball to go into the glove and just something as simple as that can make a huge difference in a guy’s ability to play defense.

Whether it be on the infield or on the outfield body position, you know how you’re bending at your knees, how you’re hinging at your waist, how your feet are working through the ball, all those little things that you can isolate in foundational drill work can get ingrained into a guy’s system and that opens up a multitude of things for them to be able to do.

I believe that if they do not have that base, then it’s gonna be a really inconsistent road as you kind of work your way up and try to develop into a reliable and eventually, hopefully an elite defender.

Mark: Another phrase you emphasize is “Engage the game.” What does that mean?

Darren: It starts with your pre-pitch. Are you consistently putting yourself in an athletic position to get a great first step, every single pitch for 150 pitches a night? And so it may sound simple but think about the mental focus that you need to be able to do that over the course of (a year).

Engaging the game is just understanding the situation, understanding the scoreboard, meaning that if there’s a man on, where am I supposed to be on a certain type of ball and where am I supposed to throw the ball?

When you are constantly teaching that side of the game – and that might be in between innings when a guy makes a good decision, when a guy makes a bad decision, when you’re consistent with that teaching aspect in the same way that you’re consistent teaching the physical aspects, now we’re kind of tag-teaming the two parts of defensive play that are required to become an elite defender.

And those apply on the infield side as well as the outfield side equally. I think the consistency of teaching that part of the game is just as important as teaching the physical aspect consistently.

Mark: Isiah Kiner-Falefa talked on our podcast about learning every position. Can you speak to that?

Darren: I don’t know when this happened, but people got stuck on a position saying, ‘Hey, I’m only a shortstop. I’m only a center fielder, I’m only a catcher.’

The example that I would always use would be if you were a minor leaguer who played shortstop coming up with the Yankees, you weren’t going to play shortstop (with Derek Jeter there). So you were either gonna get traded or you had to be open to playing a different position.

When you learn how to play different positions, you’re giving your manager, you’re giving your coach different options on how to use you. If Alex Cora or any coach has interchangeable parts, then game-to-game, they can fit the pieces in different ways to put their best puzzle together every night.

When guys move off shortstop, I always love to use the expression, ‘If you move to second base, you’re not a second baseman, if you move to third base, you’re not a third baseman. You’re a shortstop playing second or playing third.’

Shortstop is the spot on the infield where you have to be most active with your feet. You can’t be lazy, pre-pitch. You always have to be moving, mentally engaged, and knowing so much about so many different things.

And I think if you keep that same type of mindset, when you move off shortstop, now, all of a sudden, you’re playing different spots with the athleticism at shortstop that puts you now in a position to be an above average defender at those other spots.

I think the physicality of being able to play different spots, the mental side of being able to play other spots just provides so much more value for you as a player. In the sense of how you’re allowing a manager to use you.

Mark: If you could fix one thing about how people at a young age are taught defense, what would it be?

Darren: A lot of kids are ingrained on a very fundamental base, everything perfect with two hands and being very ‘textbook’ in how to field ground balls. And that’s a really good thing.

I played for Fred Hill at Rutgers, an old-school baseball guy. Everything was two-handed, everything was fundamentally sound.

When Rey Ordóñez first came up with the Mets, he had a signature play where he would slide to catch the ball, and in one motion, would catch the ball, pop up and fire across the diamond.

I taught myself how to make that play. And my freshman fall at Rutgers, I make that play during a practice and Coach Hill says, ‘Pretty nice play, Darren. Make it again and your ass is gonna be on the bench. Make the play the right way.’

Now with some perspective, I think that fundamental approach took away from the athleticism that a Nolan Arenado plays with. Nolan knows how to make fundamental plays, but he’s an artist with how he does stuff, in that he does stuff that coaches wouldn’t teach.

I’ve come to an understanding now, being around it over the last 20-plus years on the professional level and then with those six years in the middle as a college coach, to be able to understand how athleticism opens up so many different options on how you might be able to make a play.

I wish more kids would be able to be exposed to (that) at an early level. Yes, you need that fundamental base, but I think guys need to be given the option – to let athletes be athletes.

That doesn’t mean you turn what should be a fundamental play into ridiculous highlight-reel play when it doesn’t need to. But I think when you give guys that option to be able to show off their athleticism, now, all of a sudden, you’re able to build something off that foundational base.

The better athletes can make better plays. And the more ways a guy can make a play, the better of an infielder that they’re going to be.

We’ll drill something with two hands and the very next rep would be one hand, and then we go back to two hands, and sometimes it’s setting our feet up to throw, sometimes it’s everything on the run. And these are all with the same exact types of ground balls.

It’s to help guys understand that they have options and to allow their athleticism to shine through to find the best option for them to make a play. And I think that gets taken away when guys are ingrained in the idea that you’re only allowed to be a fundamental player. And sometimes it takes time to get them out of making the play perfectly when they’ve been hammered on it for so many years. It takes some time to build off that, for them to get out of.

Mark: Last thing: Can you give me an example of a player that you could point to and say: that guy did a great job of learning how to play defense?

Darren: Carlos Asuaje opened the season as a utility-guy backup playing three, four days a week.

He started to swing the bat well and that provided him more opportunities. He never played third base before. He had this bad habit of letting the ball play him.

And so he would constantly turn routine ground balls into base hits because he would backtrack on the ball such that his body would be going into left field when he would have to make a throw in the complete opposite direction. It took a long time to get the backtracking out of his system.

At one point he went to go get the ball and he made an error. It was what I would call an aggressive error. And when he came into the dugout, he was pissed off about making an error.

I went up to him and I gave him a big hug because I was so excited because that was like one of those moments where it clicked for him, even though he didn’t make the play, it clicked for him in terms of going after the ball the right way. Slowly but surely, those plays became routine outs.

To see that progress, weeks and months in the making, that’s what defense is. It’s about being able to progress in that manner. It was a credit to him for putting the work in, and by being able to isolate a specific type of play over and over in a practice setting, over time it does translate.

He wasn’t a star major leaguer, but he got to the big leagues as someone who, I don’t think a lot of people ever thought that he would’ve made it. To see that all happen was really exciting.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length