it’s time to look beyond the defensive metrics we were given.

By MAX CARLIN AND CONNOR AYUBI

Public NBA draft analysis is a game of proxies. With some 3,000 games played by 100 or so NBA-relevant prospects each year, no individual could possibly consume — let alone accurately evaluate — the complete sample of players that make up an NBA draft class. So, scouts turn to stand-ins, whether they be subsets of the games each prospect plays, statistical indicators, or ideally some combination of the two.

In some areas, this approach is relatively sound. Armed with tools like play type information, shot locations, and assist data, one can begin to check and legitimize observations from film analysis. You could, for example, verify that a prospect who appears to self-create a high frequency of rim attempts on film does so with the above information.

Yet defense remains something of an unquantifiable anomaly. Most commonly, those looking to corroborate their eyes on the defensive end turn to steal, block, and the composite stock (steal + block) percentage. The idea behind using these measures as surrogates rests upon the notion that they correlate to notable defensive impact (or at least to basketball IQ or physical tools).

The issues block, steal, and stock percentage present as proxies are two-fold: what they do capture and what they don’t capture.

An instructive block

Consider this sequence from Precious Achiuwa, whose lunge at the ball-handler for no discernible reason generates a layup attempt. Likewise, his ability to plant hard, explode in the opposite direction, rise quickly off one, and extend for the block erases it:

This block represents a false positive in the department of winning impact. Purely by the measure of blocks, this play is indistinguishable from a textbook rotation punctuated by a swat. Instead, a faithful retelling of this scenario would capture that Achiuwa has the physical tools and wherewithal to recover but created his team’s disadvantage in the first place. There are laudable and noteworthy projectional elements to the sequence but it is not a positively impactful one–pieces of information that we at Sports Info Solutions insist on keeping distinct and evaluating separately.

Instead of approximating what we don’t see, we’re empowered to watch everything and log every defensive contribution a prospect makes (or fails to make) for an entire season.

Meanwhile, the limitations of what blocks and steals don’t capture far outweigh what they do. Typically, blocks and steals provide results-based information on the conclusions of 2-3% of a prospect’s defensive possessions, while entirely missing the rest of the approximately 80% of possessions in which a prospect engages in at least one meaningful defensive action, according to our research.

At SIS, we’re lucky to have a staff of basketball experts capable of consuming and evaluating the hundreds of thousands of possessions prospects put on film each draft season.

Among others, we have at our disposal an overall defensive impact statistic called Defensive Winning Impact (DWIMP). Instead of approximating what we don’t see, we’re empowered to watch everything and log every defensive contribution a prospect makes (or fails to make) for an entire season. With such a powerful metric at our disposal, we are enabled to investigate questions like the validity of stock percentage as a defensive proxy.

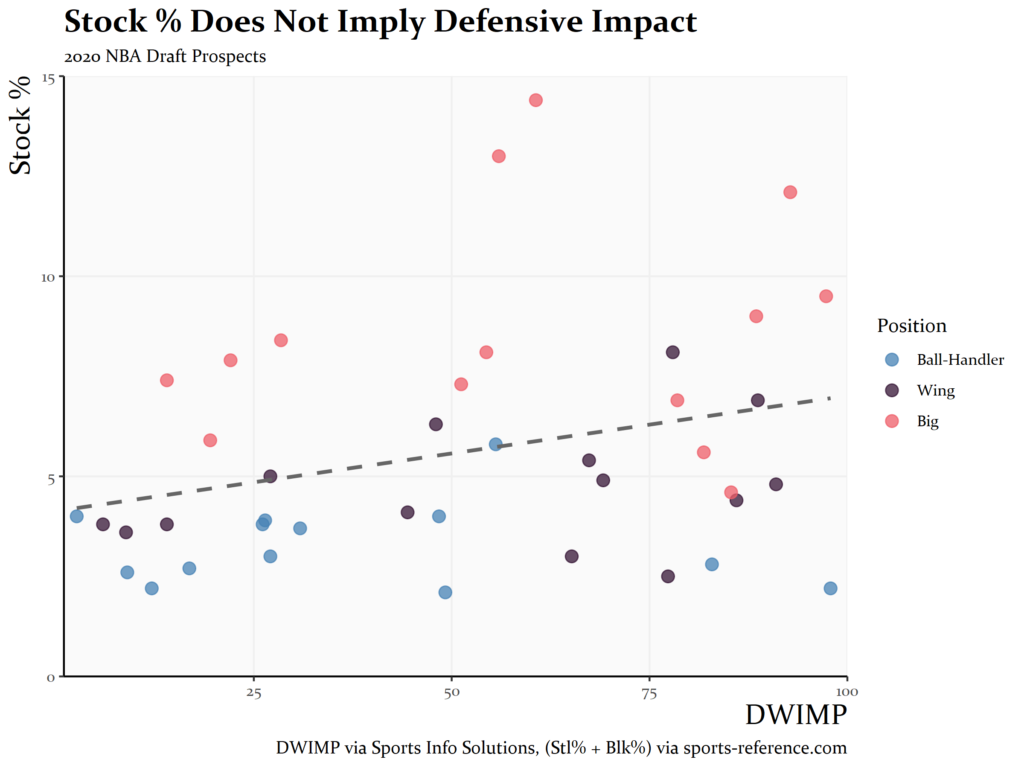

Our findings? Neither stock percentage nor its component parts are particularly useful stand-ins for defensive impact:

For this analysis, we focused on quality-controlled data from the 2020 NBA Draft. The unimpressive visual relationship between stock percentage and DWIMP translates to a statistically insignificant correlation.

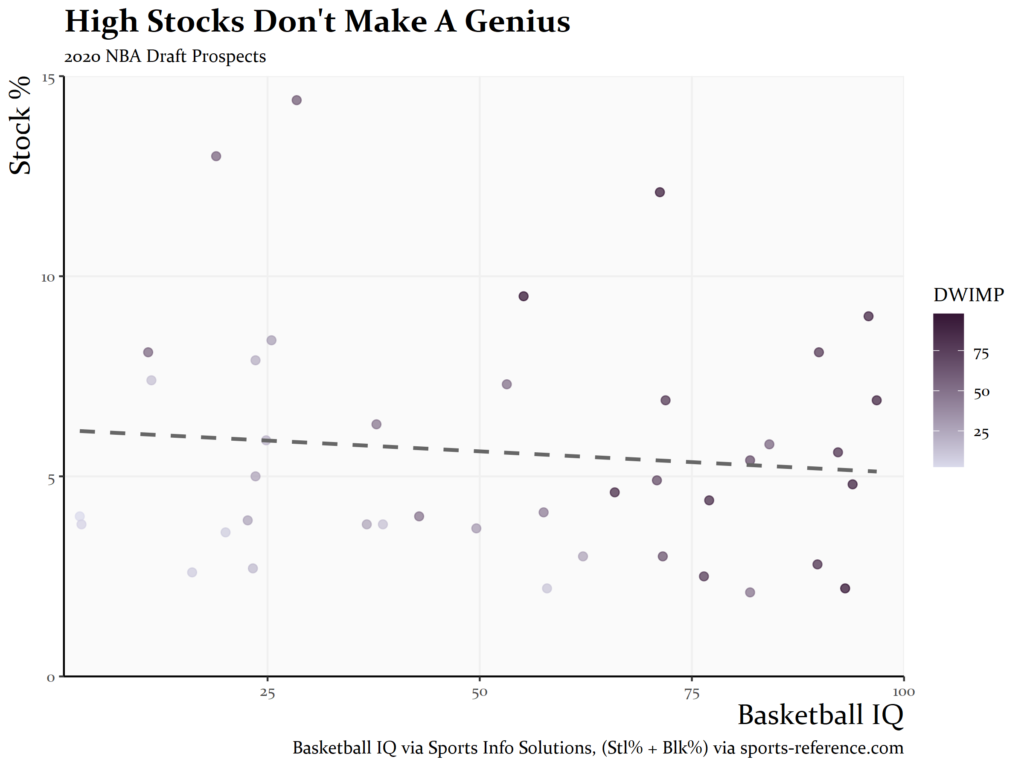

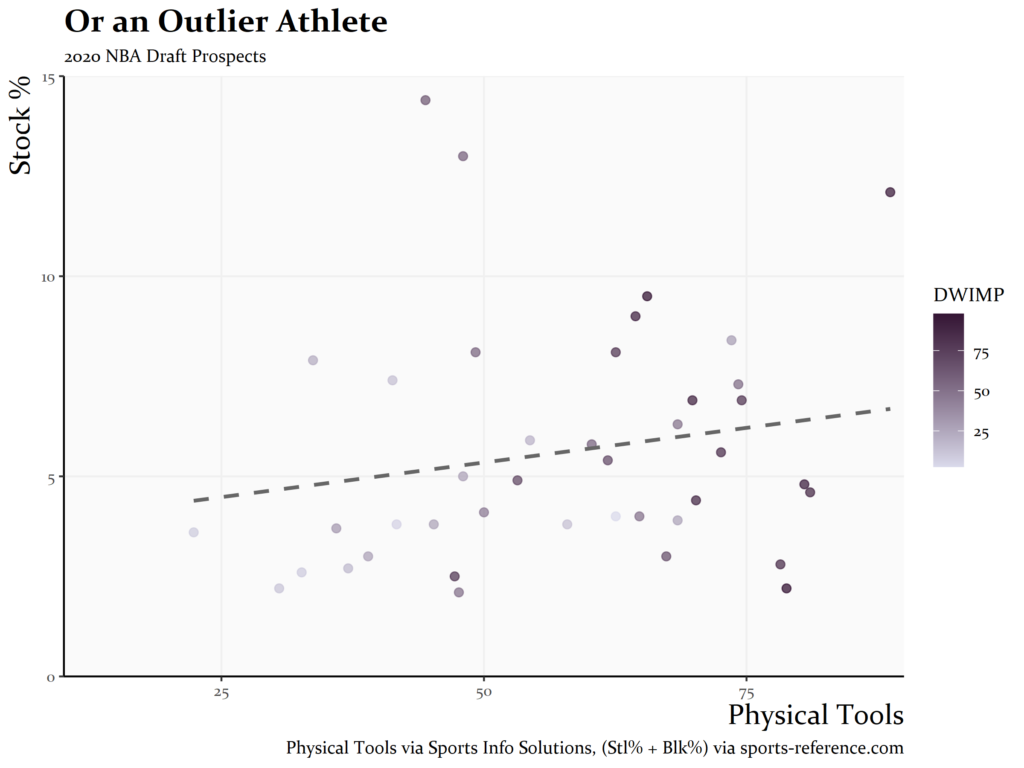

Furthermore, a player’s stock percentage provides no indication of their ratings in our Basketball IQ or Physical Tools metrics:

An illustrative pair

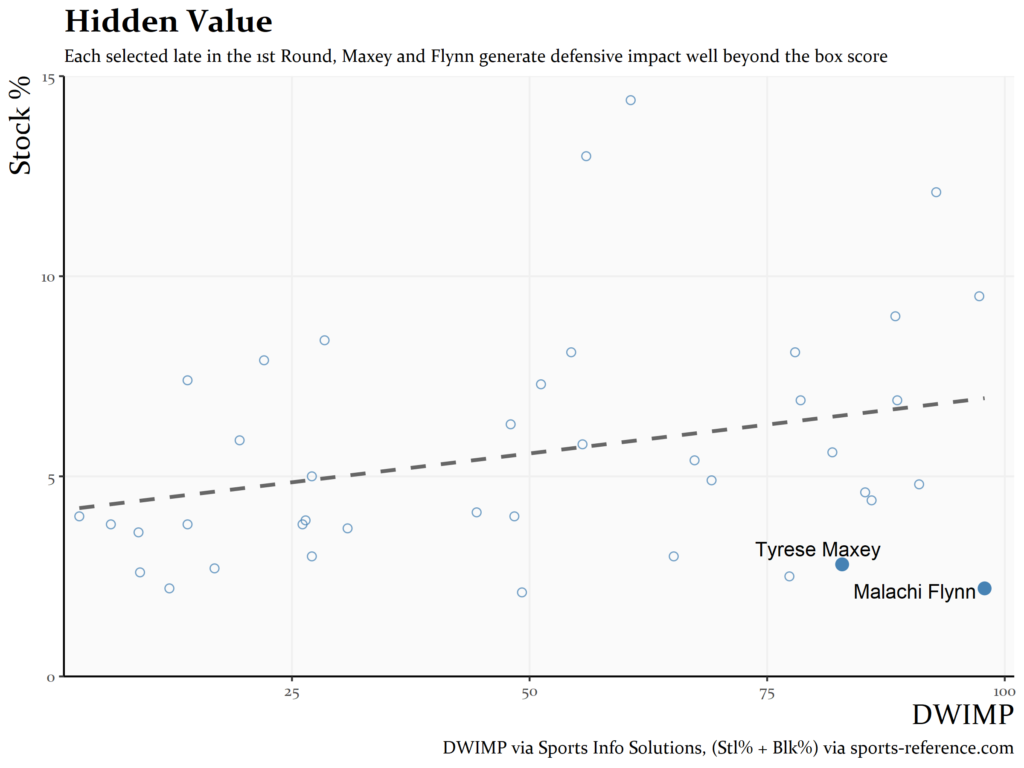

Since DWIMP is both more comprehensive in its scope and nuanced in its evaluation than stock percentage, we see some players with highly discordant DWIMPs and stock percentages:

DWIMP diverges most from stock percentage for a pair of instructive ball-handlers. Both Malachi Flynn and Tyrese Maxey underwhelmed by conventional defensive playmaking stats last year, but the more comprehensive defensive analysis underlying DWIMP captures the steady impact both guards provided through reliability.

Flynn and Maxey ranked first and second respectively in off-ball defensive consistency among the 18 ball-handlers in our sample last year. While neither player made a ton of plays on the ball, both satisfied their responsibilities as team defenders. It was rarely electric, but it was clinical, and the two significantly improved their teams’ defenses accordingly:

A tag here, a stunt there, throw in a nice dig to force a ball pickup–the box score tells you Maxey does nothing on this possession, but his true impact is undeniable.

On the ball, the pair maintained their steadiness. Flynn sat first and Maxey third among ball-handlers in our point-of-attack defense metric, driven by unsexy factors like ranking first and second respectively in screen avoidance:

On top of technical excellence, traditional stats fail to even capture the full gamut of defensive playmaking. They miss the effort, activity, and spatial awareness underlying the non-steal deflections that were routine to Flynn, who ranked second among ball-handlers in our On-Ball Disruptions metric, which accounts for things like pressures and deflections in addition to steals and blocks.

Just as the two did what was demanded of them to add value, they avoided crippling mistakes that concede value. Flynn placed first in our entire 50-player sample in both defensive discipline and defensive IQ, while Maxey ranked second among ball-handlers in those metrics. Avoiding low-effort plays and limiting bad gambles, Flynn and Maxey added defensive value not through occasional excitement but mundane excellence.

Though Flynn and Maxey succeeded through — broadly speaking — one defensive style, none of this is to say the only way to provide defensive value is by eschewing defensive playmaking in favor of reliability. High lottery picks like Patrick Williams and Onyeka Okongwu, for example, posted both gaudy DWIMPs and stock percentages; high block, steal, or stock percentage does not mean bad defense.

they do as they say

Instead, our research indicates block, steal, and stock percentage don’t mean much of anything. They’re not indicative of positive or negative defensive impact, outlier or ordinary physical tools, basketball ingenuity or incompetence.

Block, steal, and stock percentage are not bashful. They are exactly what they say they are: the rates at which players accumulate blocks and steals. They are limited by the constraints of what blocks and steals themselves are–an inaccurate pass that simply falls into a player’s hands is a steal.

To infer more from block, steal, and stock percentage does a disservice to those metrics. As such, basketball discourse is better served by using stock percentage and its components for their designed purposes rather than as proxies for true defensive impact.