Since his 2015 arrival in Ann Arbor, Jim Harbaugh has resurrected the Michigan program in Bo Schembechler’s image. From donning the glasses to emphasizing “The Team, The Team, The Team”, Harbaugh introduced the visuals. With consecutive Big Ten championships and College Football Playoff appearances, the wins have followed.

Harbaugh has even continued the offensive tradition he himself ran as quarterback under Schembechler back in 1986. With 36 years and several offensive revolutions between the two teams, the tactics have definitely changed. But while the methods differ, the philosophy remains the same. The Wolverines, both old and new, jab defenses continuously with the run behind their superior offensive lines, patiently waiting to knock them out with the play action pass.

Between the different styles, rules, and innovations of each era, comparing offenses from one period in time to another rarely provides any useful information. But even with these issues, the 2022 Wolverines look statistically similar to those from 1986. The 1986 Wolverines ran 69% of the time, compared to the 63% that the 2022 Wolverines do. When ranking each among their respective peers, the 1986 team ranked 21st in rushing attempts FBS teams, while the 2022 team ranked 9th.

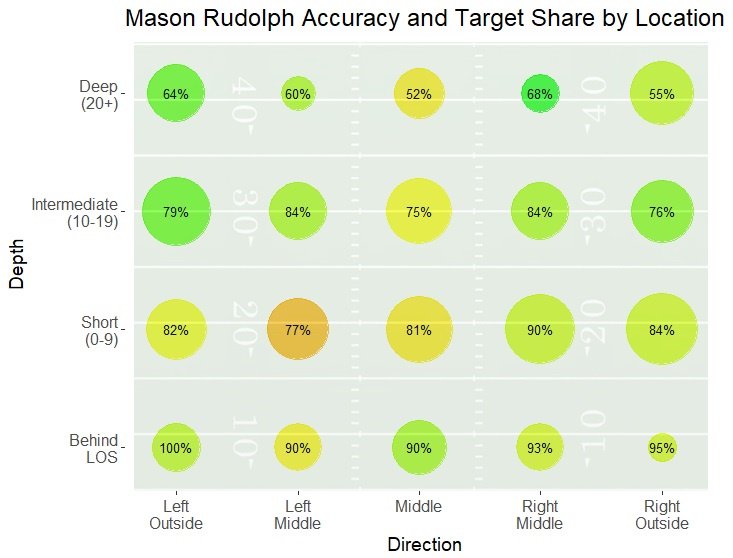

In the backfield, players from both teams share several similarities. Both quarterbacks, Harbaugh in 1986 and J.J. McCarthy in 2022, have nearly identical lines in most major metrics.

Harbaugh: 65% comp pct, 2,729 pass yards, 151.7 passer rating

McCarthy: 65% com pct, 2,376 pass yards, 155.4 passer rating

At running back, Jaime Morris ran 209 times for 1,086 yards in 1986, good for 5.2 yards per carry. Blake Corum and his injury replacement Donovan Edwards have done even better this season, with Corum averaging 5.9 yards per carry on 247 attempts, and Edwards gaining 7.5 yards per carry on 117 attempts.

But the offensive line makes this production possible. John Vitale, later voted a member of the 1988 College Football All-America team, led the 1986 team at center. Jumbo Elliot, a future Pro-Bowler,” started at tackle for Schembechler.

For the 2022 Wolverines, Outland Trophy Winner Olusegun Oluwatimi centers the line, which as a unit has won the Joe Moore Award in consecutive seasons. The line as a whole ranks 3rd in Total Points (PE per play) and 8th in Expected Points Added per play (EPA/A) this season. Among all FBS linemen who have played over 500 snaps, no Michigan starter ranks lower than the 78th percentile in PE per play.

Despite similar tools and a shared philosophy, the teams differ in their offensive packaging. Schembechler’s offenses operated under center, almost always with two running backs, and often three. Harbaugh’s offenses work from the gun usually with only 1 running back, instead adjusting the number of tight ends and receivers in the formation according to the situation.

With many runners in the backfield, the Wolverines of old had a variety of ways to run the ball. To attack quickly inside, Michigan ran dive or iso. To hit off tackle, the Wolverines called power. To stretch the defense outside, the quick pitch and stretch came into play. To get all backs involved, Schembechler would break out the Wishbone and run the veer.

Modern Michigan stresses the same points in the defense, but in different ways. Inside zone makes up the plurality of all Michigan runs at over 44%, while Duo ranks as its best base run. The Wolverines rank 2nd in Duo usage among all FBS teams, and among high-usage offenses average the 2nd-highest PE per play.

While the modern run game differs greatly from that of the past, power remains a popular run at all levels. The Wolverines have run it 61 times this season and rank 8th in PE per play when using it. Paired with counter, the Wolverines have two time-tested ways to run the ball in the C gap.

To get the ball to the perimeter, the Wolverines typically call either the sweep on the ground or screen in the air. Their most effective method, however, comes from the option. Schembechler used the option with veer to get the quarterback involved in the run game and to attack multiple parts of the defense at once. Harbaugh pairs the option with inside runs, usually zone, for a similar goal, as he gets an inside threat with the running back and an outside threat with the quarterback on the same play. Ranking 1st in PE per play when the quarterback keeps the ball on the option, Harbaugh’s Michigan can run effectively to the outside while also threatening the interior of the defense.

As with their respective runs, Schembechler’s and Harbaugh’s play action passes differ in design and execution. But in purpose, the principles remain the same, and sometimes can make plays from 36 years apart look eerily alike. To attack the middle of the field, both offenses contain a concept with a cross and a post. In the clips below, Schembechler’s receivers run the routes on opposite sides of the formation, while Harbaugh’s align on the same side. Each team, however, called the play with the same idea in mind.

To attack deep to the outside, each offense used a play sending a wideout down the seam only for a player from the backfield to wheel into the secondary.

As with the runs, each offense’s play action passes reflect its respective era in terms of tactics, but represent Michigan’s philosophy with regard to its intentions.

Football’s offenses and defenses constantly grow and change over time. While instilling the fighting spirit and methods of his mentor and predecessor Bo Schembechler, Jim Harbaugh has found a way to mesh this philosophy with modern offensive theory. By implementing the traditional smashmouth style with current strategy and tactics, the Wolverines have replicated, and could exceed, the program’s past successes.