On March 3, in a spring training game between the Boston Red Sox and Minnesota Twins, the Red Sox deployed a new shift for the first time in a game. Naturally, the Red Sox did this against Joey Gallo, who pulls the ball more than almost anyone in MLB. Gallo ranked No. 1 in pull percentage in 2022 for left-handed hitters with a rate of 55% (among those with a minimum of 250 plate appearances).

Boston moved CF Adam Duvall to short right field in the “triangle”. Raimel Tapia, the left fielder, is in CF slightly shaded towards left and the right fielder Alex Verdugo is in straight away RF. Gallo had to be rolling his eyes as he walked into the batter’s box. All this talk in the offseason about short RF being a land full of hits for lefties was quickly shot down by this alignment.

The key to the new shift rule is that it restricts only infielders from moving. Infielders must be on the infield dirt and on their side of second base. Second basemen can’t be playing in shallow right field and we won’t see 3 infielders in the triangle defense, or as we call it at SIS, “a Full Ted Williams shift.” And of course, there’s no more Manny Machado catching fly balls in the right field corner.

The new rules don’t have any restrictions for outfielders though. Outfielders can go anywhere they want. Teams can still do 5-man infields if the situation calls for it. This also means that we can see new versions of the Full Ted Williams shift we’ve become so accustomed to.

As we’ve learned with shifts in the past, hitters won’t change their approach just because the defense is giving them a wide open side of the field. This shift won’t be different, but the risk is certainly higher for defenses than shifts we’ve seen in the past.

Data is king when it comes to shifts and Gallo’s data fully supports using this shift against him. This made me wonder, who else could have this shift used against them?

I looked at all left-handed hitters and found nine players that have similar ball-in-play data in terms of ground ball rates and pull rates that I wanted to take a closer look at. All these players saw traditional shifts regularly the past few years. The new shift, leaving LF wide open, means a higher degree of risk in shifting these guys.

So I’m going to act as if I’m an advance scout, with recommendations on how I would shift these players. I’m also going to keep in mind that I can’t just judge off the hitter’s tendencies. I have to look at my pitcher too and understand there are certain nuances to my choices.

I used a combination of FanGraphs ball in play data (which we’re the source for) and Sports Info Solutions visuals to make assessments. With each player, you’ll see their outfield fly ball and line drive spray chart, though I also consulted their groundball charts and their charts for offspeed pitches in making these writeups.

The rankings in each section are percentile rankings of the 132 left-handed hitters with a minimum of 150 plate appearances

Joey Gallo

>>Percentile rankings in parentheses

| Pull % | Oppo% | Fly Ball % | GB + LD Pull% | Fly Ball Oppo% |

| 55% (99th) | 18% (3rd) | 53% (99th) | 73% (99th) | 24% (1st) |

Gallo meets all the criteria for a player for whom we’d want to use this shift. He rarely hits opposite-field fly balls. He has the highest grounder and liner pull percentage and 85% of his grounders and short liners are to the right side of 2B.

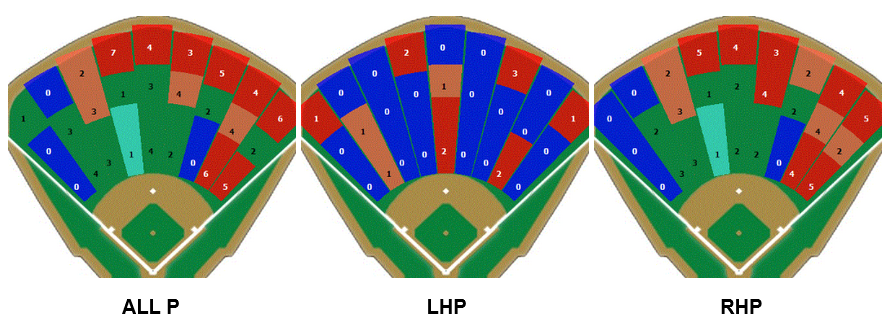

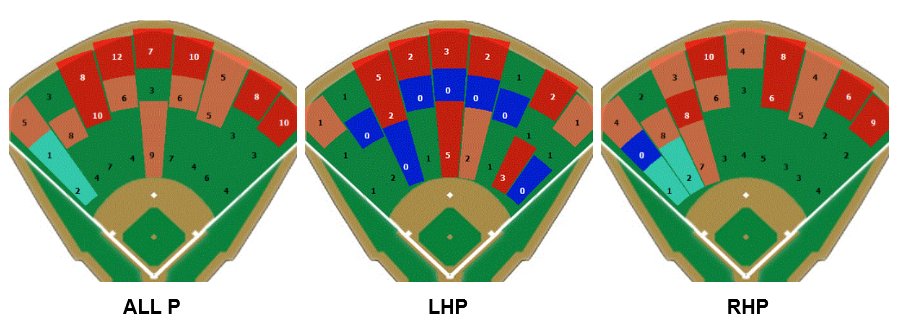

Here’s his spray chart on flies and liners to the outfield.

Recommendation: Shift at will.

Against RHP, he will hit more fly balls but not many to LF. If he hits a grounder or liner it’s going to be pulled. Also strikes out 38% and walks 14% of the time.

Against LHP, Gallo hits a ton of ground balls to the pull side and struggles to put the ball in play, strikes out 48% and walks 12%.

If he beats us to the opposite field once there’s a good chance it won’t happen twice in a series.

Daulton Varsho

>>Percentile rankings in parentheses

| Pull% | Oppo% | Fly Ball% | GB + LD Pull% | Fly Ball Oppo% |

| 55% (99th) | 16% (1st) | 44% (75th) | 63% (92nd) | 23% (1st) |

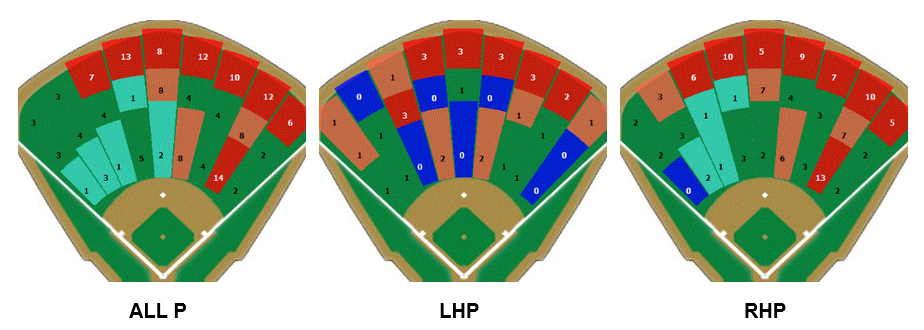

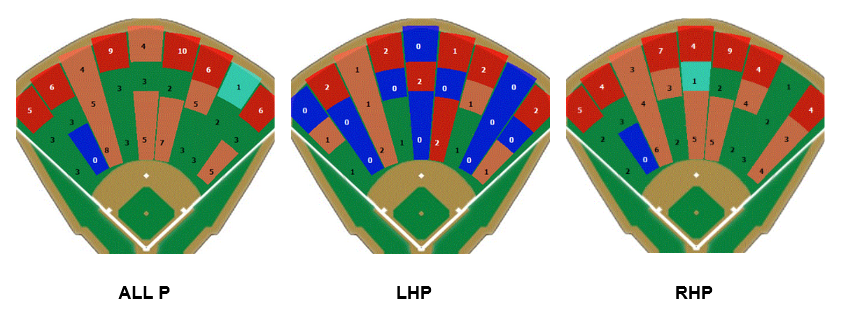

Recommendation: Use shift vs. RHP. Can use vs. LHP but that comes with a high risk factor. Shift more with high-percentage ground ball pitchers and against RHPs with low fastball usage.

With RHP on the mound Varsho hits more fly balls but still doesn’t use the opposite field. Hits into the “triangle” position of short RF more than anywhere else on flies and line drives. RHP with low-fastball usage is the best instance to shift.

Against LHP he hits more grounders and pulls them. Won’t use the opposite field on fly balls often but he will on line drives.

Kyle Schwarber

>>Percentile rankings in parentheses

| Pull% | Oppo% | Fly Ball% | GB+LD Pull% | Fly Ball Oppo% |

| 44% (72nd) | 19% (8th) | 51% (97th) | 60% (85th) | 27% (2nd) |

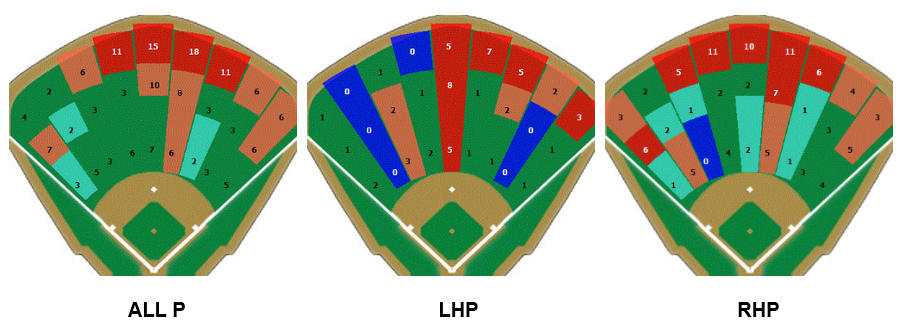

Recommendation: Shift with LHP

Against RHP he will use every part of the field. Takes advantage of pitchers not wanting to throw inside to him. Fly ball percentage and his ability to use all parts of the field make him a no-shift option.

When facing LHP, Schwarber doesn’t hit fly balls to the opposite field. He can hit a line drive that way but not frequently enough to worry about. A LHP with low fastball usage is an exceptional time to shift.

Jose Ramirez (specifically as an LHB)

>>Percentile rankings in parentheses

| Pull % | Oppo% | Fly Ball% | GB + LD Pull% | Fly Ball Oppo% |

| 49% (93rd) | 20% (13th) | 50% (92nd) | 59% (83rd) | 27% (2nd) |

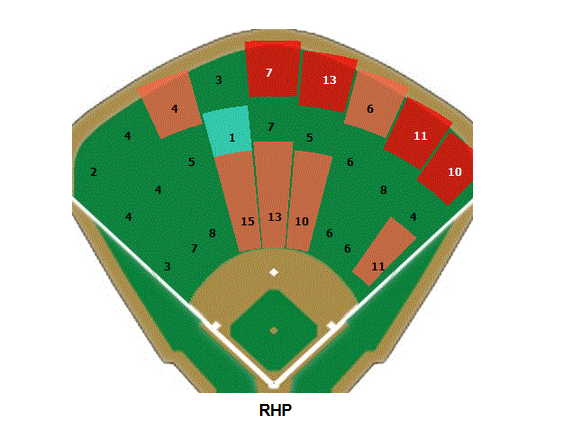

Recommendation: Do not shift.

Ramirez does a great job of using all fields, has barrel control and takes what the pitcher is giving him. He does have the tendency to pull grounders and line drives (did so 83% of the time as a left-handed batter) but his fly ball numbers make shifting dangerous.

Mike Yastrzemski

>>Percentile rankings in parentheses

| Pull% | Oppo% | Fly Ball% | GB + LD Pull% | Fly Ball Oppo% |

| 45% (76th) | 23% (32nd) | 46% (82nd) | 60% (85th) | 38% (46th) |

Recommendation: Despite how often he pulls his grounders and short liners (nearly 90% of time), do not shift. Doesn’t hit enough grounders and fly ball trends contradict the shift.

Against RHP, he has similar numbers, except for the higher line drive% and lower grounder%. Still sprays the ball around the whole field and lifts the ball more times than not.

Against LHP, Yastrzemski hits a fly ball half the time but uses every part of the field evenly. Line drives he hits mostly up the middle.

Trent Grisham

>>Percentile rankings in parentheses

| Pull% | Oppo% | Fly Ball% | GB + LD Pull% | Fly Ball Oppo% |

| 47% (84th) | 25% (53rd) | 43% (72nd) | 62% (89th) | 43% (74th) |

Recommendation: Do not shift. He has too much speed and he sprays his fly balls well.

Against RHP he pulls more grounders but hits fewer of them. Great ability to use all fields when lifting the ball.

Against LHP Grisham hits a lot of grounders but also hits a lot of fly balls. He sprays fly balls all around the field which makes him difficult to shift.

I’m going to summarize three other hitters in brief. If you want to see more details about them, you can find them on my Twitter.

Anthony Rizzo

Rizzo is risky to shift but there are a couple of caveats. When playing in Yankee Stadium we can use it with a RHP because of the short porch in RF. Our CF and RF can shade towards the opposite field. Anything hit well to RF is going to be a double or a homerun either way. Also, if you have a left-handed pitcher who is almost exclusively an offspeed pitcher, it could work based on Rizzo’s tendencies.

Cody Bellinger

Though Bellinger pulls a high rate of groundballs and line drives, he hits too many fly balls to center field and the opposite field for a shift to be worth it.

Max Muncy

Though Muncy pulls nearly 90% of his grounders and short liners is another for whom it’s mostly high-risk to use this shift, except in highly-specific situations. The one time to use it would be with a lefty pitcher with a high ground ball rate (maybe a Tim Mayza). He sprays his fly balls too much for it to be worthwhile otherwise.

For more detail on these hitters and “The Joey Gallo Shift,” follow Dom on Twitter at @domricotta15