Category: MLB

-

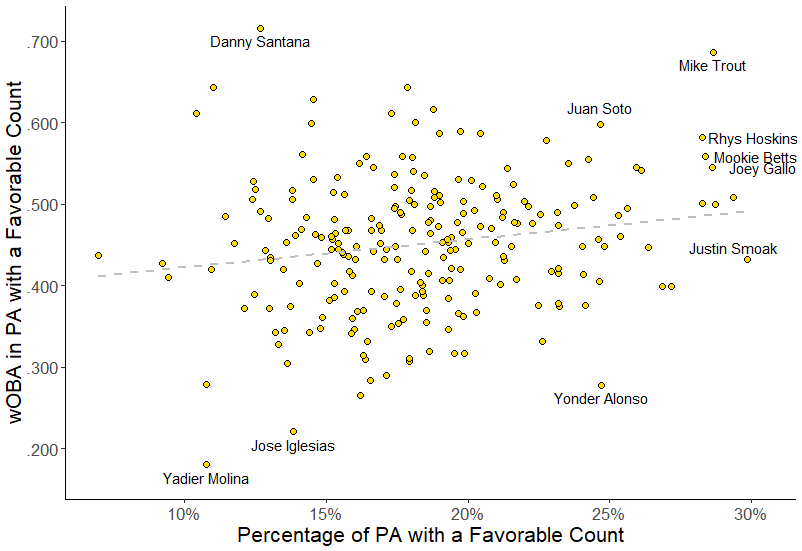

Which hitters reach favorable counts?

By

Which hitters get into favorable counts, like 2-0, 3-0, and 3-1? And which hitters then do damage?

-

What’s The Deal With Bryce Harper?

By

The $330 million man hasn’t quite lived up to expectations in his first season in Philly.

-

Which Teams Are Best at Drafting, Developing and Displaying DRS?

By

How has your favorite team fared at developing defense?

-

New baseball podcast episode: Mike Ferrin wants to be Byron Buxton

By

In this episode of the SIS Baseball Podcast (click here to listen), Mark Simon (@MarkASimonSays) begins by marveling at Zack Greinke’s defense (1:05). Mark then talks to MLB Radio and Arizona Diamondbacks broadcaster Mike Ferrin (@Mike_Ferrin). Mike makes his case for the best team in baseball (3:25) and discusses how much organizations value defense in…

-

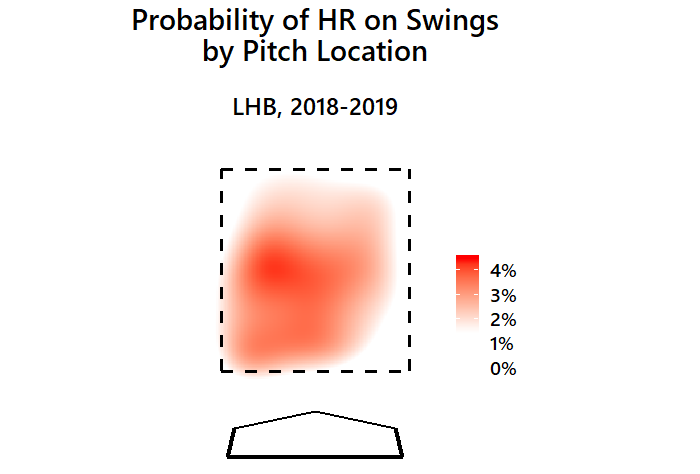

Visualizing Home Runs by Pitch Location

By

A look at which pitch locations generate home runs, and how it compares to several years ago when the home run wasn’t as common.

-

Ball off the Wall: Which outfielders make mistakes, which have not?

By

Who has the most misplays on playing balls off the wall? Who has made few or none?

-

Reintroducing FieldingBible.com

By

We’ve added lots of statistics to the FieldingBible.com website. Come check it out.

-

-

Inside the numbers on Urshela’s improvements

By

Urshela has had the magic touch when it comes to hitting the ball hard.

-

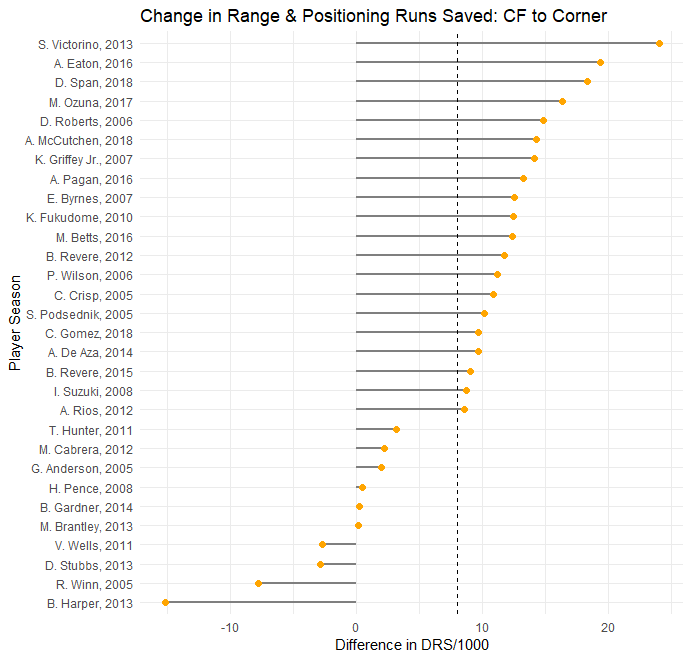

The Effect of Outfield Position Changes on DRS

By

How does DRS rate center fielders when they move to a corner? How do corner outfielders rate when they move to center?