By ALEX VIGDERMAN

It’s not often that a move that everyone talks about as a potentially interesting story actually comes to fruition.

Since Tom Brady’s official departure from the Patriots, people have been intrigued by the possibility of another former MVP stepping in to replace him in Cam Newton. Now we have the opportunity to find out not only what a Patriots offense looks like without Tom Brady, but what it looks like when it’s headed by one of the most prolific rushers to ever play quarterback.

Of course, with Bill Belichick’s penchant for changing game plans wildly from week to week, it’s probably not prudent to try to guess at how the Pats’ offense might change with Cam under center. Instead, we’ll just compare Newton to Brady along a few dimensions, assessing where the Patriots might be able to sustain their performance and where they might fall back a bit.

Newton certainly represents a downgrade from pre-2019 Brady, but last we saw Cam for a full-ish season he was roughly as effective as Brady was last year, so perhaps Patriots fans shouldn’t be concerned? Let’s run down a few narratives that could help inform the discussion.

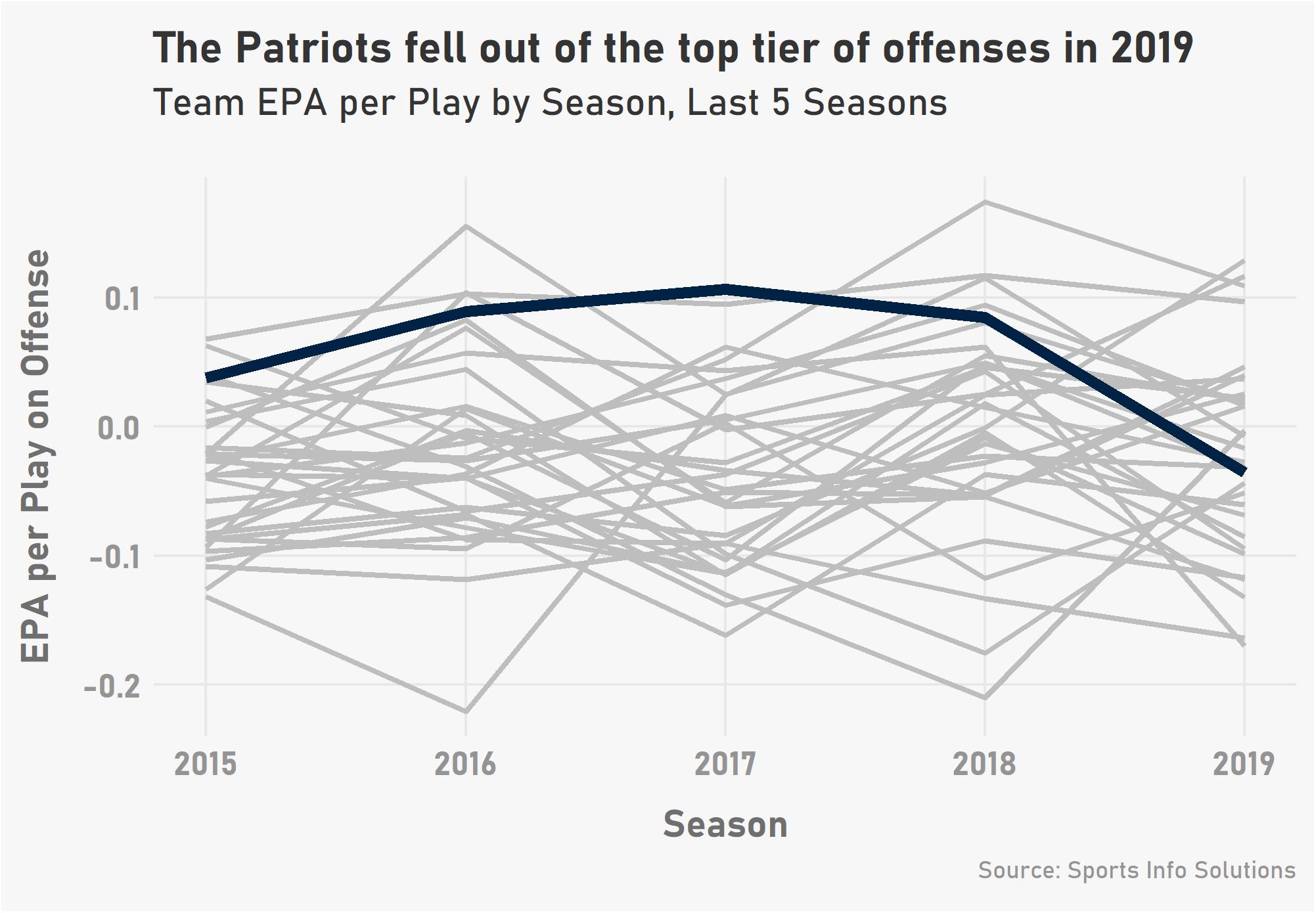

The offense was in decline already, so the risk is low

The biggest thing to keep in mind here is that the hole left by Brady isn’t nearly as big as it would have been had he departed a few years earlier. The Patriots had been mainstays in the upper tier of offenses with Brady at the helm, but 2019 was definitely a down year. Look at their decline in Expected Points Added per play.

Brady himself didn’t decline as much in terms of total value as he did on a per-snap basis thanks to a top-five attempt total. He ranked barely outside the top ten in Total Points among quarterbacks, but on a per-play basis was very much in the middle class.

Tom Brady’s Ranks Among Quarterbacks by Season

| Season | Total Points | Total Points per Play |

| 2016 | 7th | 1st |

| 2017 | 3rd | 9th |

| 2018 | 6th | 8th |

| 2019 | 11th | 18th |

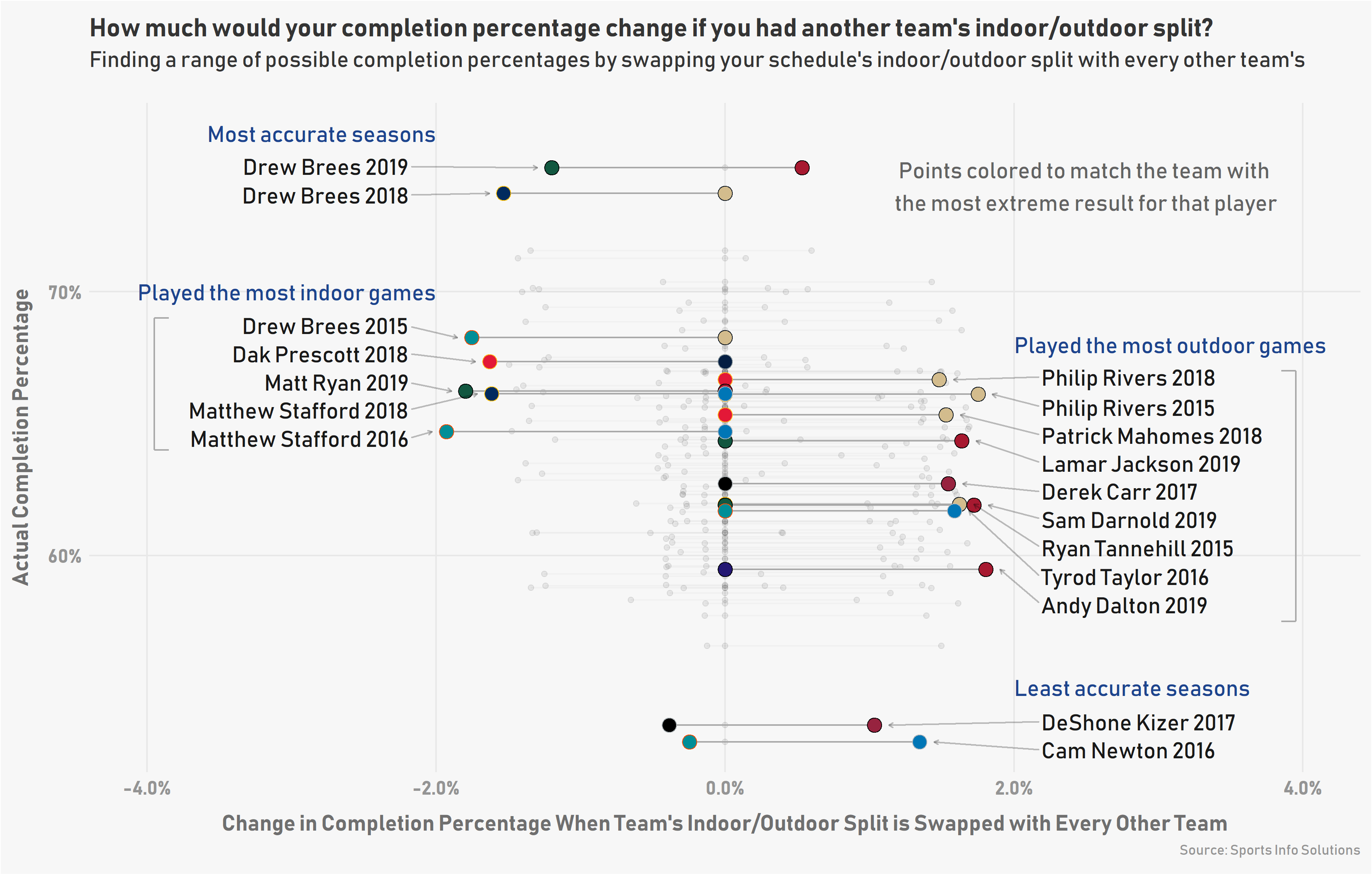

Newton’s precision in a quick-hitting New England offense

This might be surprising given their reputations, but Newton has actually outperformed Brady on quick-hitting throws over the last two years. His 9.9 Total Points per 60 plays (TP/60) on zero-to-one step drops outpaces that of Brady (7.7) since the start of 2018.

A corollary of the narrative about Newton’s accuracy is that he has a history of making the best out of bigger, slower receivers like Kelvin Benjamin and Devin Funchess because he doesn’t have Brady’s pinpoint accuracy. Moving from an offense headed by two sub-six-foot receivers (D.J. Moore and Curtis Samuel) and to one with some bigger targets (N’Keal Harry and Mohamed Sanu Sr.) could work out better for Cam than it had for Brady.

For what it’s worth, if one of these quarterbacks does better with bigger targets, it’s Brady. Over the last two seasons, his Total Points per 60 plays when throwing to receivers at least 6’0″ tall improves, while Newton’s declines.

Total Points per 60 Plays by Targeted Receiver Height, 2018-19

| Under 6’0″ | 6’0″ or Taller | |

| Cam Newton | 11.9 | 7.4 |

| Tom Brady | 10.6 | 13.2 |

Adding a new dimension via the running game

Newton’s athleticism is the most obvious X factor. You don’t need any stats to convince you that Newton’s rushing ability could open up the offense in a way we’ve never seen. The Ravens showed with their transition from Joe Flacco to Lamar Jackson what kind of transformation an offense can make to support an elite athlete.

That said, Cam hasn’t actually been that valuable with his legs, at least in recent seasons. Looking at the four years we have Total Points data for, he has actually cost his team value in three of the past four seasons. Some of that is the likelihood of fumbles on quarterback runs. But over the last four years he’s still only accumulated 6 Total Points on the more than 300 carries in which he didn’t fumble.

It’s worth acknowledging that Newton’s impact on the running game isn’t just limited to his own carries. As Steven Ruiz points out, his presence should open up opportunities for his running backs because other teams have to account for his rushing ability. But considering the wear and tear his body has already sustained and the lack of history the Patriots have with such athletes at quarterback, it’s fair to be conservative on Newton’s potential value on the ground. But on a one-year incentive-laden contract, perhaps anything is possible schematically.

The Final Word?

The Patriots’ signing of Cam Newton is a spike of interest in what has otherwise been a quiet offseason among all the other things going on in the world. Unfortunately, there are so many question marks involved in this transaction. We’re talking about an injury-riddled player with a totally different athletic profile to that of a player who had spent two decades on the same team. Anyone trying to assess the situation analytically should be forgiven regarding the uncertainty.

But it seems to me that these key narratives that people might point to for one reason or another are tending to go the opposite direction of what you’d think initially. And with Bill Belichick still at the helm of the Patriots, perhaps it is the best course of action to sit back and wait instead of assuming we know what will happen in Foxboro.