Coaches don’t win games. Players do. Many coaches create intricate, elaborate playbooks with dozens of fronts, stunts, blitzes and coverages in the hopes of turning their defense into the next Steel Curtain. But few win by putting scheme ahead of personnel.

Conversely, teams with better players usually win. Tactically-inept coaches have won with the talent advantage. But they never win as much as they should. Great coaches put their personnel first with a scheme that maximizes each player’s abilities. No defense does that better than Illinois.

With five games left in the season, Illinois has already surpassed all expectations. Predicted to finish 6th in the Big Ten West, Bret Bielema and his Fighting Illini currently lead the division. For the first time in 11 years, Illinois is ranked. In under two years at the helm, Bielema has the program rolling, largely thanks to its defense.

Illinois’ defense, coordinated by Ryan Walters, leads the FBS in both points (8.9) and yards (221.1) allowed this season. But the advanced metrics treat Walters’ defense just as well. The run and pass defense rank 15th and 3rd in Points Saved Per Play (PS Per Play) and 3rd and 1st in Expected Points Added Per Play (EPA/Play), respectively for Power 5 teams. With a simple scheme that prioritizes its players’ abilities, Illinois appears to have turned a corner.

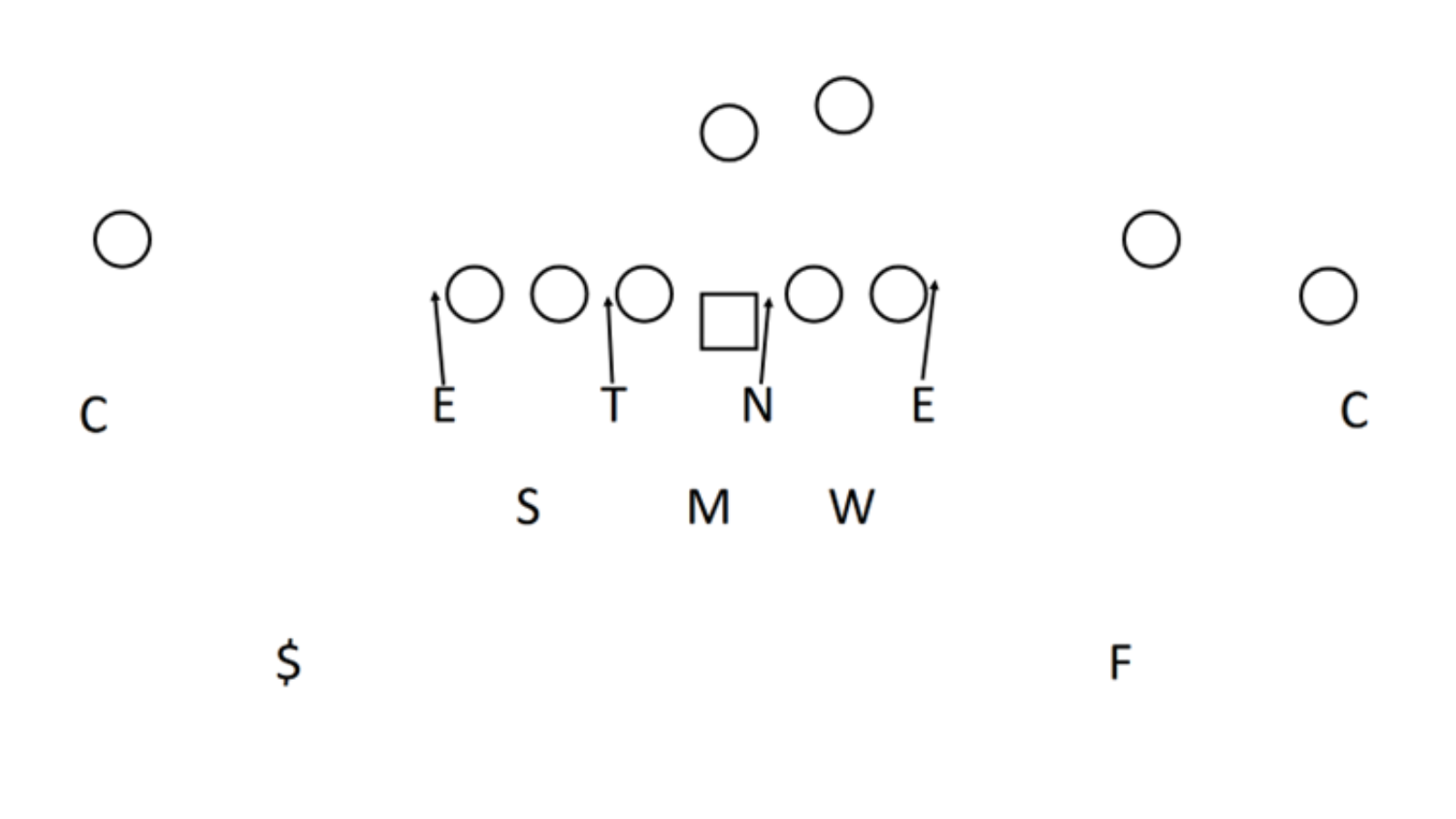

The Illini most commonly-used look shares a resemblance to the 46 defense, also known as the Bear front. Illinois normally plays with three down linemen and 2 outside linebackers on the line of scrimmage, with a middle linebacker and five defensive backs.

In passing situations, Illinois will occasionally go to a 4-2 or even a Psycho look:

The Illini stunt and blitz often, which is not uncommon for teams with limited talent. This season they send five or more pass rushers 49% of the time, 3rd most in the FBS, and pressure the quarterback 49% of the time, which ranks 6th. Even when they send four or fewer, the Illini pressure the quarterback 39% of their pass rushes, best in the FBS.

On the back end, the Illini typically have one deep safety sitting up to 25 yards from the line of scrimmage. The rest of the defensive backs align as if in man coverage. The alignment is usually true to the assignment, as they play Cover 1 on 67% of non-screen passes. Cover 3 gets called the second most at 14%, with the occasional Cover 2 called as well, sometimes even from the 1-high shell.

Even with the blitzing, Illinois does not have a complex defense. Because of its simplicity, the Illini can adjust its personnel within the structure of the defense to best counter the offense. Facing 10 personnel, the Illini align in their base.

Given 11 or 20, the Illini sub in a linebacker into the box to the tight end side, or move Sydney Brown (30) to that spot.

Against 12 or 21, the Illini bring in Isaac Darkangelo (38) as the extra linebacker to match the muscle.

The specialization does not stop there. For the front, the wide side of the field determines the formation strength and in turn where everyone aligns. Keith Randolph Jr. (88), their best interior lineman with .096 Points Saved Per Play against the run, lines up across the field-side tackle, while Jer’Zhan Newton (4) faces the boundary tackle. At outside linebacker, Calvin Hart Jr.(5) goes to the field, Seth Coleman (49) to the boundary. The linebackers take it even further than the defensive line. When Gabe Jacas (17) or Alec Bryant (90) come into the game, the starter still in the game plays to the field.

In the defensive backfield, rather than using the wide side of the field to determine matchups, the Illini use individual skills, much like a basketball defense. Tahveon Nicholson (10) and Devon Witherspoon (31), both in the top 10 in Points Saved Per Play against the pass, cover the wideouts. If the two primary wideouts align on the same side opposite a nub, the corner follows the receiver:

In some instances the corners follow specific receivers no matter where they align. Tahveon Nicholson followed Indiana’s DJ Matthews Jr. (7) in the closing minutes of their matchup, covering him in the slot despite normally playing wide.

Jartavius Martin (21) covers the third receiver and Sydney Brown the fourth. Kendall Smith (7) plays the deep safety unless the offense goes heavy, in which case Darkangelo subs him out and Martin plays deep. Despite the reputation of the specialized skills of the free safety, the Illini perhaps treat this position the most interchangeably.

In addition to beneficial personnel matchups, a few other factors have contributed to Illinois’ strong defensive performance. Ranking 2nd in time of possession this season, the Illini offense has kept the defense off the field, giving the opposition fewer chances to score against a well-rested defense. Additionally, the Illini have benefitted from soft scheduling.

Illinois played five of its first seven games at home, and the rest of the division has disappointed this season. Wisconsin came out so poorly it fired its coach (with some credit due to Illinois), and Iowa may have the worst offense in the FBS. In spite of the opportunity, none of Illinois’ division foes has stepped up to take over for either.

But given that the Illini allowed nearly 35 points per game in 2020 en route to a 2-win season, Bielema and Walters cannot get enough credit for the turnaround. With only three seniors in the defensive starting lineup, the defense could even improve in the coming years. Illinois’ simple scheme has its players confident in both their abilities and assignments. Combined with the best possible matchups at every position, the defense has found a way to lead the team into the driver’s seat of the Big Ten West.