You might have noticed a few new columns in the stat pages on Fangraphs.com. Fangraphs will have glossary definitions posted in the near future, but for now, you can learn more about these stats here. Here’s our explanation on Team Shift Runs Saved.

In 2010, Baseball Info Solutions (BIS) began tracking defensive shifts for the first time. That season, Video Scouts observed 2,463 shifts on balls in play from watching video. That number decreased slightly to 2,350 in 2011, but after that shift usage exploded. In 2012, the number of shifts nearly doubled from the previous season. By 2014, that number was up to more than 13,000. In 2016, it jumped to more than 28,000. In the 2018 season, there were nearly 35,000 observed shifts on balls in play.

With it widely known that shift usage has skyrocketed, the obvious question that arises is: Which teams are most effective in using it? For that, there is the stat devised by BIS, Shift Runs Saved. It is listed on the Fangraphs team fielding pages as rTS.

Calculation

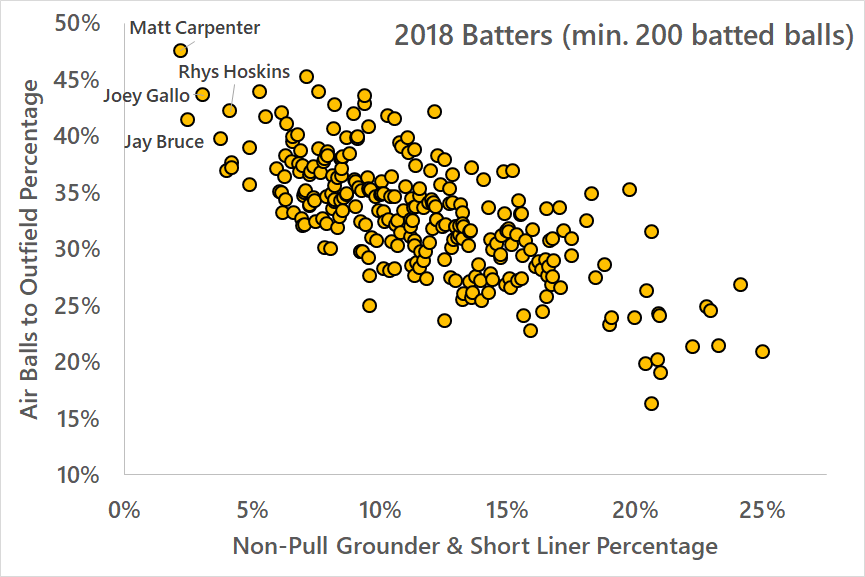

rTS measures whether a shift is doing what it is supposed to do – get outs on ground balls and short line drives that wouldn’t have been achieved with the traditional infield alignment. The calculation is done at the team level rather than the individual level.

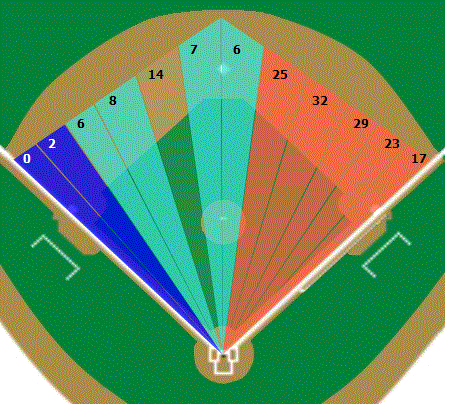

This stat takes how hard the ball was hit and what direction the ball was hit, and then it compares how often a team was able to make an out on that type of ball in play while using a defensive shift to how often the league was able to make an out on that type of ball in play on the whole. Positive credit is assigned for successful plays made and negative credit is given for plays not made, which is eventually converted to a Runs Saved value. The values are summed for all grounders and short liners against defensive shifts to get a seasonal value.

For example, let’s say a batter hits a groundball 70 miles per hour through the infield at an angle 17 degrees off the first base line. This play may be made 25 percent of the time in an unshifted defense within a two-year period specific to that date. If the play is made, the defensive team gets a collective credit of 0.75 (1 minus 0.25). If the play is not made, the defensive team receives a 0.25 debit. The credit or debit is then converted into a run value, and all of those are summed into a seasonal total.

Note that velocity is measured as distance divided by time, rather than speed off the bat

Why Shift Runs Saved?

Shift Runs Saved became necessary because of The Lawrie Defense. In 2012, the Blue Jays began playing third baseman Brett Lawrie in shallow right field during their defensive shifts. If Lawrie made a play, he was receiving an abnormal amount of credit in the BIS Range and Positioning system because third basemen don’t typically make plays on balls hit to short right field. Lawrie racked up value that other third basemen could not because their teams were not playing them in that area.

Given that it is the team’s decision to use shifts and to position fielders, it was best to assign the value to the team as a collective unit.

Shift Runs Saved became the solution to that issue and is the best way to measure performance specific to when a team is utilizing a defensive shift.

How to Use Shift Runs Saved

rTS shows how many runs a team saved or cost themselves on groundballs and short liners against a shift in a given season.

rTS is more of a cumulative metric than an efficiency metric. Often teams that shift the most will have the most rTS, but that doesn’t mean they have the highest frequency of getting outs on a per-shift basis.

Keep in mind that a team’s reasons for being good or bad in rTS could be due to other factors, such as how it positions its fielders within shifts and the quality of the players on the field at that time.

Context

With the number of shifts continually increasing, the totals at the top of the rTS leaderboard are similarly increasing. Context is best determined by rank within the league within that given season. Almost every team has a positive rTS total because shifts do what they are supposed to do — they allow a team to defend more effectively against those hitters who tend to pull a lot of their grounders and short liners.

The 2017 season was the first one in which a team recorded at least 30 rTS. In 2018, five teams had at least 30 rTS. The Diamondbacks led the majors with 39, followed by the Athletics (36), Rays (31), Twins (31), and Tigers (30). Four teams had negative rTS, meaning that using the shift cost them runs — the Phillies (-10), Pirates (-6), Nationals (-4), and Mariners (-4).

Things to Remember

– BIS categorizes shifts as follows:

* If 3 infielders are on one side of the infield, it is considered a Full Shift. If at least 2 infielders have deviated significantly from their usual positioning, or if one infielder is playing deep into the outfield (Usually the second baseman playing shallow right field), that is considered a partial shift These are combined into one category on the Splits Pages, “Traditional Shifts.”

* “Non-Traditional Shifts” are Situational shifts not covered under the definition of traditional shifts, such as playing the infield in.

– Shifts are determined from video review by trained video scouts based on observations of game broadcasts.

– Shifts are not recorded for balls that are not put into play (strikeouts, walks, home runs) and measuring shift effectiveness does not take anything other than grounders and short line drives into account.

Links For Further Reading

Shift Data! – Fangraphs

2019 Shift Update – Bill James Baseball Handbook

Why Baseball Revived a 60-Year-Old Strategy Designed to Stop Ted Williams – FiveThirtyEight