You might notice a few extra columns of stats now available on Fangraphs.com stat pages. They’ll have glossary explanations up in the near future, but for now, here is the definition for Strike Zone Runs Saved.

Strike Zone Runs Saved (rSZ) is a stat created by Baseball Info Solutions (BIS) that ascertains the contribution each player is making in getting more or fewer called strikes than average, converted to a run value. It can be found on the Fangraphs stat pages. The catcher, pitcher, batter and umpire all have an independent influence on whether a pitch is called a strike or a ball. For the purposes of the Fangraphs stats pages, our concern is with the performance of the catcher and whether he is performing above or below average in this regard.

The idea of framing pitches is that the catcher is trying

to ensure that taken pitches in the strike zone are called strikes and

attempting to get called strikes on pitches thrown out of the strike zone through

a variety of means (pre-pitch body positioning, subtle body movements upon

catching the pitch, or keeping the body and glove still when catching the

pitch).

Catchers who are good at this can have a significant

positive impact on the performance of their pitching staff. They have good rSZ

numbers. Conversely, catchers who are not good in this area can negatively

impact their pitchers’ performance and have a poor rSZ value.

Calculation

Before computing rSZ, the calculation starts with Strike

Zone Plus/Minus.

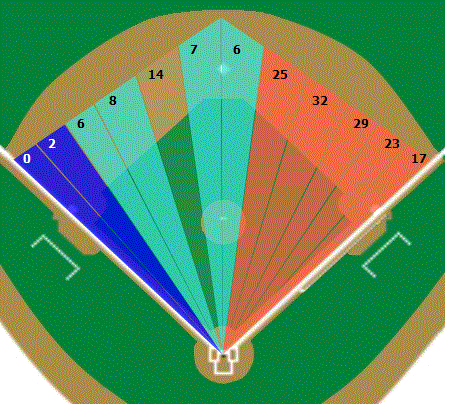

To compute Strike Zone Plus/Minus, the pitch is categorized

by its location, the count the pitch was thrown in, the proximity of the pitch

to the catcher’s target, and the batter’s handedness. That allows the determination

of the percent likelihood that each pitch is to be called a strike. The full

array of these strike percentages represents our Strike Zone Plus/Minus Basis,

i.e., the basis by which credit is assigned if the pitch is called a strike or

debit if the pitch is called a ball. This uses a rolling basis of four years of

data to determine how to bucket our pitches.

If a pitch is called a strike, there is positive credit

to be awarded (plus) to the players involved. If a pitch is called a ball,

there is negative credit to be assigned (minus). The amount of positive or

negative credit given depends on how likely that pitch was to be called a

strike in the first place, which is known from the Basis that was previously

calculated.

For example, if a pitch is thrown that is one inch off

the outside edge of the plate and 20 inches off the ground, to a left-handed

batter, in a 3-2 count, and misses the catcher’s horizontal target by 3.5 inches, there is an estimated 46

percent chance that the pitch will be called a strike. Therefore, if the umpire

calls the pitch a strike, then there are plus-0.54 Strike Zone Plus/Minus

points (or “extra strikes”) to be allotted to the participants on the pitch.

However, if the umpire calls the pitch a ball, then there are minus-0.46 points

to be divvied up among the four parties.

An iterative approach is used to divide up the credit or

debit for each pitch. You can learn

more about that here.

Each catcher’s seasonal Strike Zone Plus/Minus is the sum

of his Plus/Minus for every pitch he caught that season. From there, the

Plus/Minus can be converted to a run value. The run value is calculated by

taking our pitch results from the four-year period, calculating the run

expectancy associated with each ball/strike count, and then finding the

difference in the change in run expectancy between the next pitch being called

a ball and the next pitch being called a strike. Those changes in run

expectancy are averaged into a single run value.

Why Strike Zone Runs Saved?

As is noted in the definition for Defensive

Runs Saved, the value of this statistic is in its allowing you to

compare all players using the same set of parameters. A run value stat allows

you to assess a player’s ability relative to how much it helped his team win.

rSZ also is notable for its ability to divvy up the value

between all involved parties, rather than give all the credit to the pitcher,

batter, catcher or umpire. As such, rSZ tends to value catchers less extremely

than other publicly available pitch-framing metrics.

How To Use Strike Zone Runs Saved

The best way to think of rSZ is relative to the average

catcher. A player with 10 rsZ is 10 runs better than the average catcher.

rSZ works best as a player accumulates more sample size

for the season. A catcher could have had a couple of good days or a couple of

bad days within a small sample that would distort his value.

One thing worth remembering is that if you have two

catchers with the same rSZ value, but one has caught 100 games and the other

has caught 80, the two may be tied in rsZ, but the catcher with 80 games caught

is faring better on a per-pitch basis.

Context

In 2014, Hank Conger and Mike Zunino shared the major

league lead by saving 16 runs with their pitch framing. Dioner Navarro ranked

last. He cost his team 17 runs with his framing. The gap between best and worst

was 33 runs. The differential dropped to 25 runs in 2015 and 24 in 2016 before

climbing back to 31 runs in 2017.

In 2018, Max Stassi, Yasmani Grandal and Tyler Flowers led

the majors with 10 Strike Zone Runs Saved. Tucker Barnhart and Nick Hundley

ranked last with -9. The gap between best and worst shrunk to 19 runs.

With that in mind, rSZ can be broken into the following

tiers:

Strike Zone Runs Saved Rules of Thumb

|

Defensive Ability

|

rSZ

|

|

Gold Glove Caliber

|

+10

|

|

Above Average

|

+5

|

|

Average

|

0

|

|

Below Average

|

-5

|

|

Poor

|

-10

|

Things to Remember

– Pitch locations for each pitch are hand-charted by

Baseball Info Solutions video scouts. BIS does its best to ensure the accuracy

of this information and that it is the best information that is publicly

available.

– rSZ is one component of catcher defense that goes into

Defensive Runs Saved. BIS also charts how catchers fare at thwarting stolen

bases (rSB), blocking pitches (which makes up most of the value of rGFP), and

handling a pitching staff (rCERA).

Links for further reading

Who

is responsible for a called strike? Sports Info Solutions

Which

catchers are best at stealing strikes? Sports Info Solutions

Is

pitch-framing cheating? Fangraphs