Category: MLB

-

The Dodgers’ dominant defense

By

By Mark Simon The Dodgers are poised to not just dominate the NL West again, but to dominate all of baseball in defensive performance. The Dodgers lead MLB with 62 Defensive Runs Saved. The next-closest team entering Thursday is the Astros with 45. What’s impressive about the Dodgers is that they’ve done this after they…

-

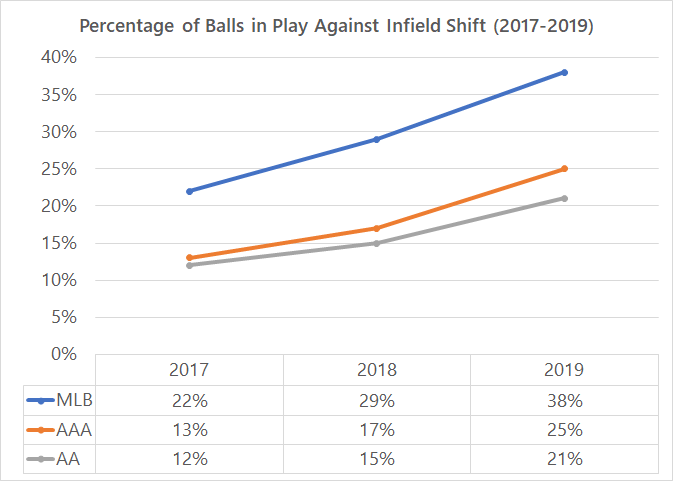

The Rise of Minor League Defensive Shifts

By

We talk a lot about shifts at the MLB level. What about in the minors? Are they rising like they are in the majors? Are they are as common?

-

What’s been behind Justin Verlander’s great season?

By

Slider dominance and defensive dominance are going hand in hand to allow Verlander to outperform his peripherals.

-

Who can we combine into the best 5-tool player?

By

You’d need someone who could hit, hit for power, run, field and throw. Basically we’re asking: How do you build a Mike Tout?

-

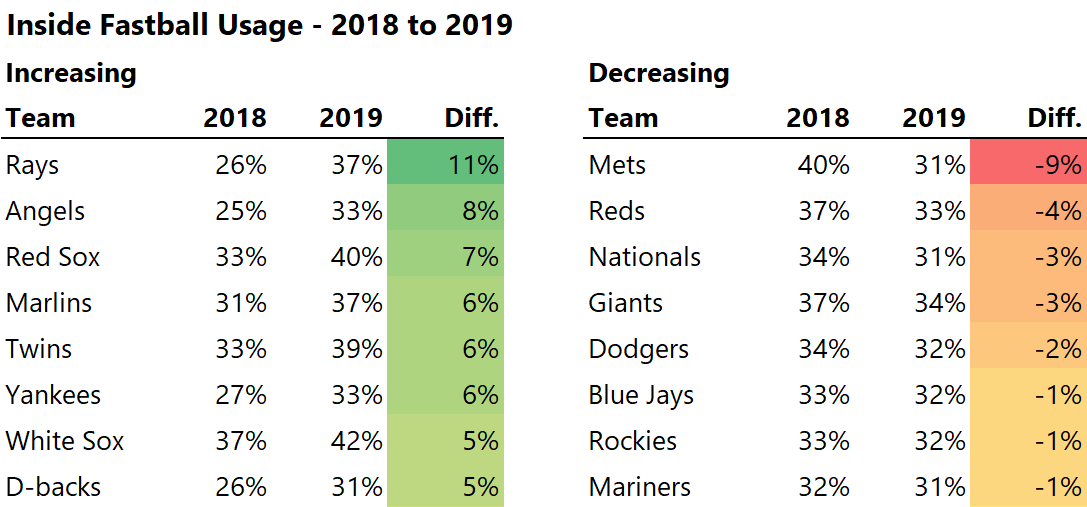

Mets moving away from the inside fastball

By

The Mets threw the highest percentage of inside fastballs in 2018. That hasn’t been the case in 2019.

-

Do fielders dive more when a potential no-hitter is on the line?

By

Jurickson Profar and Gregor Blanco made us wonder about this.

-

Home Run robberies are up … at least recently

By

5 HR robberies in the last 3 days prompted us to take a look at the season record, the current pace, and more.

-

Stat of the Week: Who is the World’s No. 1 Starting Pitcher?

By

Who is best? And who is moving up the list?

-

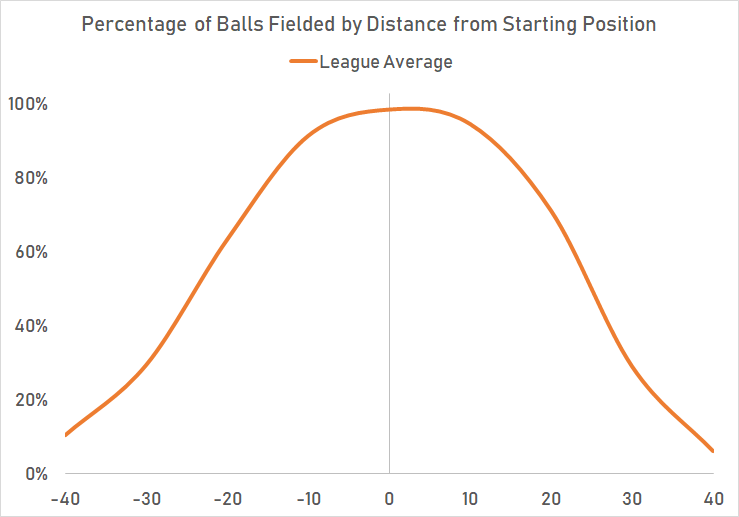

Visualizing Shortstop Range

By

A visual look at the lateral range of baseball’s best and worst shortstops.

-

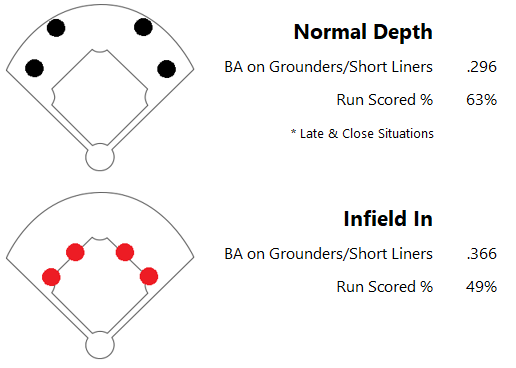

The Effectiveness of “Infield In” Defense

By

What do the numbers show about bringing the infield in?