A word association exercise kicked off with “Phillies defense” may yield responses like, “bad” or “worst team in MLB by DRS in 2021.”

While those descriptions may not be inaccurate, today we’re not here to talk about the Phillies’ defensive performance as a whole, but rather, a shift in their defensive strategy that may be leading to positive early returns.

The Phillies have never been considered pioneers of defensive positioning. SIS has tracked shift usage on balls in play since 2009, and the Phillies have been in the bottom-5 of shift usage in 6 of those seasons. The most recent of those years is 2021, in which they employed a shift on 40% of balls in play, ahead of only the White Sox.

Phillies Shift Usage through the years*(BIP)

| Season | Shift Usage | Rank | MLB Average |

| 2022 | 52% | 25 | 64% |

| 2021 | 40% | 29 | 55% |

| 2020 | 65% | 9 | 60% |

| 2019 | 36% | 21 | 45% |

| 2018 | 38% | 9 | 32% |

* Shift usage = % of Balls In Play vs a Defensive Shift

The 2020 season notwithstanding, there’s a gradual increase in shift usage as the years progress. Another note of interest is that in 2018, the Phillies’ low shift rate (from today’s perspective) was considered semi-aggressive compared to the rest of MLB. However, as their shift rates remained in the same neighborhood, shifting around the league trended upwards at a steeper rate.

Defensive strategy cannot be evaluated based solely on how often you stick your infielders somewhere unfamiliar, however. It’s certainly possible that an unshifted defense can be as effective as a shifted one in the correct circumstances.

That begs the question—with the increase in shifting, is the Phillies defense getting any better?

In 2021, when shifted, the Phillies converted 72% of groundballs and bunts to outs—good for 28th in MLB. This season, that rate has jumped to 74%, which thus far ranks 18th. If you watch the Phillies on a nightly basis, an about-average infield defense is a breath of fresh air.

Additionally, the Fightins have accrued 6 Defensive Runs Saved specific to their shift positioning, the 5th-best total in MLB (and that’s despite ranking 25th in shift usage). Last season, their 9 DRS from shift positioning was the 2nd-lowest total, behind the Royals.

So, what’s different?

For one thing, Jean Segura got taller.

Wait, that’s Alec Bohm positioned in shallow right field. Forgive me, I’m used to seeing this:

And what I got was this:

The earliest instance of Alec Bohm being positioned there is from an April 20 game against the Rockies. He wasn’t involved in any plays from there that day, but we can get a sense of where he was positioned from this clip—as deep as the edge of the infield dirt and closer to first base than second.

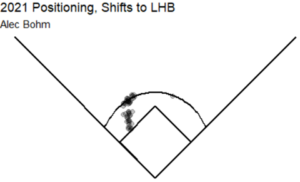

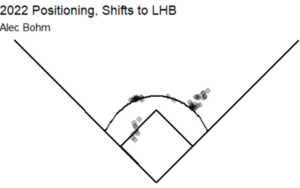

We can see a bird’s eye view of the differences of Alec Bohm’s positioning on shifts to LHBs below. For fair-comparison’s sake, I used only plays from 2021 leading up to May 9. Rest assured that even after May 9, Bohm is never positioned that far to the right of the second base bag as he is in 2022.

The consequences of this are interesting. Most importantly, Bohm is no longer out on an island on the left side of the infield when a lefty is up. The more rangy Didi Gregorius or Johan Camargo can handle the occasional oppo grounder when left all alone. That was a lot to ask of your defensively-shaky, young third baseman.

However, now that he’s playing to the right of second base, Bohm will be reading balls of the bat from an angle he’s likely unfamiliar with, which could prove problematic, but that remains to be seen for certain.

The more important wrinkle to Bohm’s change in positioning, however, is how deep he can play when a lefty is batting. When playing on the left side of the infield, infielders’ maximum depths are somewhat limited because the farther away they start from first base, the less time they have to throw—so, while playing deep can increase an infielder’s range, it can come at the cost of accurate, unrushed, timely throws.

This is null and void when the third baseman is playing in the right field grass. Their closer proximity to first allows them to play much deeper (depending on their arm strength/talent)–the consequence of this is that Bohm has much more time to react to a groundball or short line drive when he’s playing deep. This is super valuable for a guy whose range isn’t something to write home about—again, the long-term returns remain to be seen.

We have Bohm positioned approximately 184 feet from home plate in the clip below, which is the deepest we have him on a ball in play to date. In 2021, his greatest depth was approximately 153 feet from home plate (playing on the left side of the infield in a full shift against a LHB). The average estimated exit velocity on groundballs this season is approximately 85 mph (~125 feet/second)–the extra 30 feet gives Bohm about a fifth of a second longer to get to an average groundball.

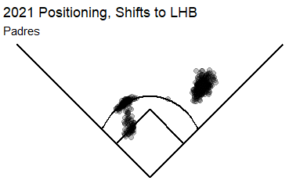

This placement of the third baseman in the hole between first and second isn’t exactly trailblazing, but it’s not the norm by any means. The Braves, Yankees, and Marlins all placed their third baseman there more than a few times, but no team did so as much as the Padres—the former home of current Phillies infield coach, Bobby Dickerson.

Previously, the Phillies rolled out talent-agnostic infield alignments that contributed to their title as one of the worst defensive teams in baseball last year. But, trends in their recent defensive alignments indicate a (long-awaited) move towards a system of maximizing the limited defensive talent they have.