Category: MLB

-

Who’s Hit More Homers Than Expected? Fewer?

By

Which hitters may have been lucky or unlucky. Which benefited from their ballpark?

-

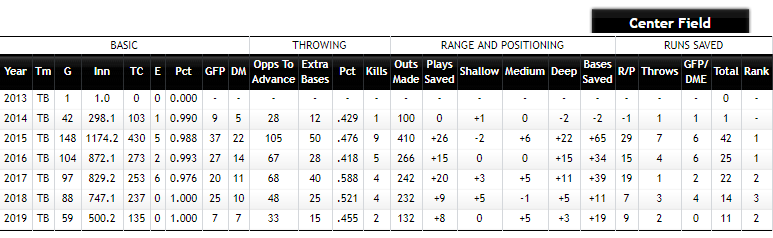

Stat of the Week: Kevin Kiermaier’s amazing Defensive Runs Saved total

By

Kiermaier recently moved into the top 10 for Defensive Runs Saved since the stat was first compiled in 2003.

-

New podcast episode: What does Moneyball look like in 2019?

By

This episode features guests who cover the Athletics, Rays and Twins discussing how those teams find edges nowadays.

-

Zack Greinke slider not what it once was

By

Some notes on the drop in performance of what used to be a key pitch.

-

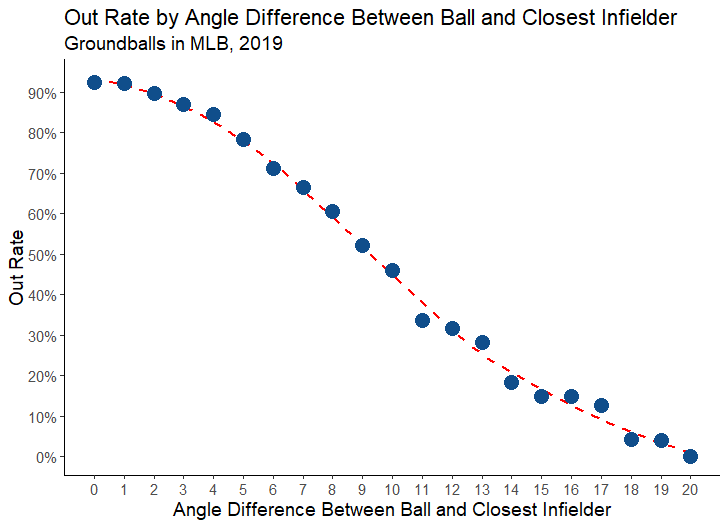

MLB’s Best Positioned Infields

By

Teams like the Astros, Rays, and Dodgers are aggressive in their positioning of infield defenders. Which teams have been best positioned in 2019?

-

How does J.T. Realmuto have 10 Defensive Runs Saved?

By

Suddenly J.T. Realmuto is one of the top-rated defensive catchers in MLB.

-

Which Pitchers Are Forced to Throw the Most Extra Pitches?

By

Whose defenses have let them down? We’ve got a list of the top 10.

-

Stat of the Week: Who is May’s top defensive player?

By

Was our choice Cody Bellinger or Matt Chapman?

-

How are the Twins getting it done?

By

The Twins are racking up wins. What have been the keys to their success?

-

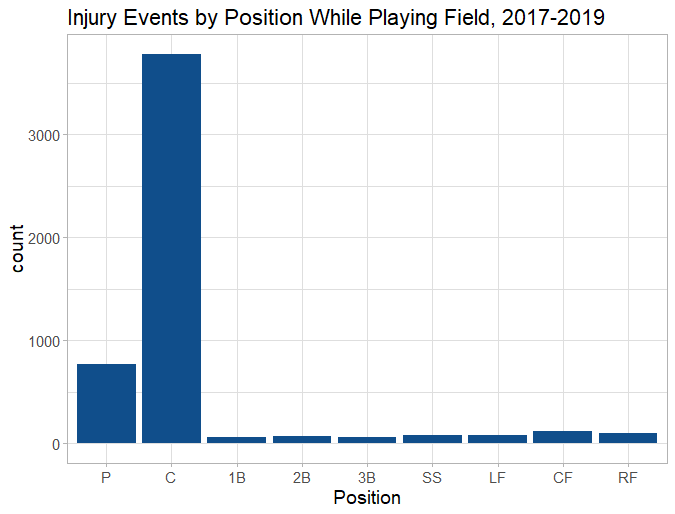

On Catcher Injury Risk and Managerial Decision-Making

By

Managers often avoid using backup catchers out of fear of injury. But how often do catchers actually get hurt?