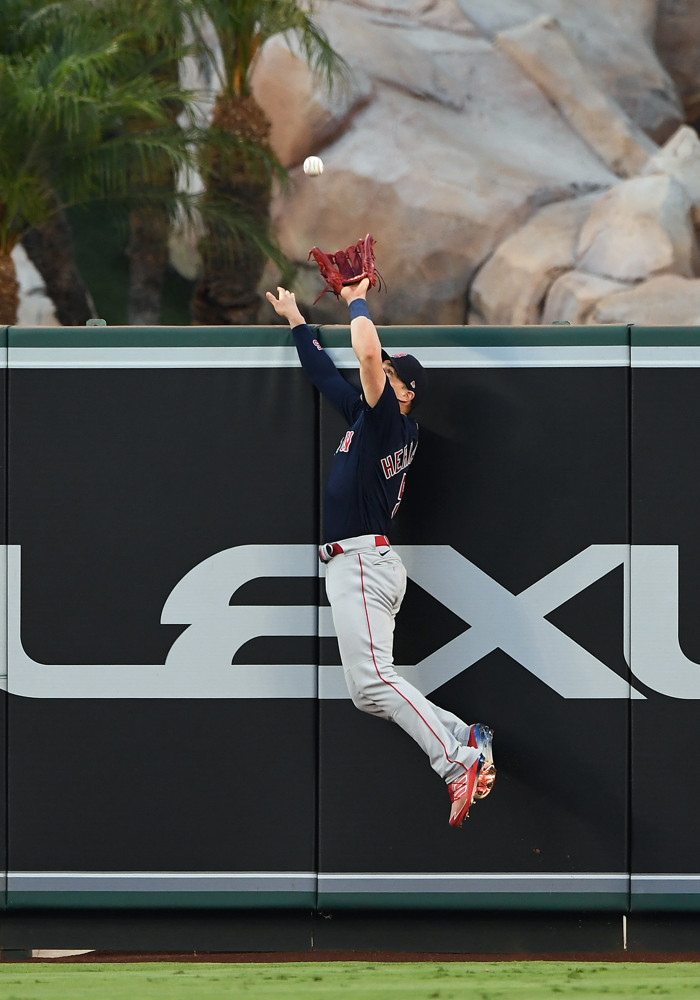

Photo: Manny Flores/Icon Sportswire

The following is an excerpt from The Bill James Handbook, Walk-Off Edition, which is available for purchase now at ACTASports.com.

In my youth, baserunning was mostly a field of conjecture. In 1960 those in the game and those into the game would have known that Maury Wills was very good at going from first to third on a single; Wills, or Aparicio, or Willie Mays or Bill Bruton or Jimmy Piersall or Minnie Miñoso or any other player who was observed to be a fast runner. They would have known that Joe Adcock was poor at going from first to third on a single, or Dick Stuart or Elston Howard or Jerry Lynch or Ted Kluszewski or anyone else who could be observed to be a slow runner.

There was a general understanding, unconnected to specific facts. Billy Bruton was said to be the fastest man in baseball, perhaps. But how often did he go from first to third on a single? 90% of the time, or 50%? No one knew. How many times a year was Bruton on first base when a single was hit? 30 times, or 200? No one knew. Since Bruton was past his 20s, had his ability to go from first to third on a single declined with age? No one could know.

What of his ability to score from second? What of his ability to move up when a pitch was in the dirt? What of his ability to score from first on a double? Unknown, unknown, unknown…. None of this was given to Heywood Hale Broun to understand. Heywood Hale Broun was a sportswriter of the time—an

actor, songwriter, author, sportswriter and broadcaster; look him up. A randomly chosen 1960s sportswriter. He knew many things that I will never know, old HHB, but how often Orlando Cepeda might score from first on a double was not one of them. Not wanting the conversation to suffer from this oversight, the sportswriters of the time would just make stuff up to fill in the gaps. I’m not suggesting that Heywood Hale Broun would make anything up, and the sportswriters and broadcasters who did would not make up specific facts. They would not tell you that Chico Fernández was 21 for 37 at moving from first base on a single, because they had never hit the realization that there was an underlying fact there that could actually be counted.

They would not tell you specific phony facts, but they would offer deep insights based on their experience. They might tell you, if they were broadcasting for the St. Louis Cardinals, that Julian Javier did not lead the league in stolen bases, but he was better than anybody in baseball at going from first to third on a single.

The broadcaster from the Philadelphia Phillies might tell you that Tony Taylor was the best baserunner in the league, and the broadcaster from the Cincinnati Reds might tell you that Vada Pinson was the best baserunner in the league, and the broadcaster for the Pittsburgh Pirates might make the same claim for Bill Virdon, and all of these people were telling you the truth as they saw it. And the guy who would tell you that no one ever went from first to third against Rocky Colavito, he was telling you his truth as well, and the guy who would tell you that Joe DiMaggio was never in his career thrown out on the bases trying to stretch a hit, he was telling you what many other people had told him.

That one was actually very common; old sportswriters from the 1940s were very fond of saying that Joe DiMaggio was never thrown out on the bases in his career. Seriously, they would say that. It was part of the DiMaggio-vs.-Willie Mays dispute. Sportswriters of the 1940s would say that Joe DiMaggio was the greatest all-around player of all time, while sportswriters of the 1950s would say the same about Willie Mays and would argue that Mays did everything that DiMag did and stole more bases in a year than DiMaggio did in his career. The 1940s guys would respond that DiMaggio didn’t steal bases, but he was never thrown out on the bases in his career. The fact that DiMaggio made four unforced outs on the bases in World Series games did not bother them, because what’s too awkward to remember, you simply choose to forget (October 2, 1936, 1st inning; October 3, 1947, 3rd inning; October 9, 1951, 7th inning; and October 10, 1951, 8th inning).

One time I heard an announcer say that Roger Maris prevented two baserunners a game from moving to third base on a single. Who’s going to argue with him? There’s no data. There’s no facts; you can say anything you want. If you liked Ellis Burks better than Barry Bonds, you could say that Burks was a better baserunner than Bonds, and nobody could prove you were wrong. It was a Rorschach space; you could see what you believed was there.

Our battle to replace speculation with knowledge began in the 1990s and began to get traction about 2004. A huge roadblock was getting people to let the facts speak for themselves. I started arguing for counts of how often a runner went from first to third on a single about 1996, I think, but for several years the discussion was backed by people who wanted to not count this and not count that. Obviously, they would say, you can’t count situations when the play starts with a runner on second base, because maybe the runner can’t go to third. (Actually, a runner from first goes to third a little bit MORE often when there is a runner on second, because he sometimes has an opportunity to move up on the throw home.) Obviously, you can’t count infield singles, and obviously singles to right field are very different from singles to left field. Singles that are hit directly at the fielder are obviously different; there’s no chance to move up on those, and wouldn’t the numbers be very different with no one out than they would be with two out?

All statistics group together unlike things to a certain extent, and I agree that it is important to recognize those differences. All doubles are not the same. A ball hit down the line is different from a hustle double in shallow center is different from a ground rule double is different from a ball that hits the wires supporting the catwalk in Tampa Bay.

But in this case, if you count EVERYTHING, count every situation in which there is a runner on first base and a single is hit, you wind up with good, meaningful data. Elvis Andrus in his career through 2022 was 74 for 111 at scoring from second base on a single, 67%, while Carlos Santana was 43 for 119, 36%.

If you just count everything, the data will speak for itself. The process of accumulating the data will even out MOST of the “bias” problems, not all of them, of course. If you throw out cases when there is a runner on second base, and you throw out infield singles, and you throw out the cases when the ball is hit right at the fielder, and then you divide the data into subgroups of one out and two out and three out and subgroups of balls hit to left, right and center, you don’t have meaningful data, you just have a lot of 3-for-6s and 2-for-4s. In retrospect, it is obvious that the data works if you just leave it alone and let it speak for itself, but it took me several years to get past the resistance from people who didn’t think that we should count these and didn’t think that we should include those.

Conceptual clarity. The point I am trying to make is that there is a big difference between the job of a statistician, which is to count things, and the job of a researcher, which is to figure out what should be studied, what should be counted, and how it should be counted. Conceptual clarity means that you have a clear, clean definition of what you are counting. You should be able to explain it in one simple, easily understood sentence. In studying baserunning, we had to focus on what was most helpful for us to count. Runners going from first to third on a single, but what else? We settled on seven major categories to describe baserunners, granting that those seven categories don’t get everything that makes one baserunner different from another. The things we published in this section in the past are:

(1) Runners going from first to third on a single. The major league norm is 28%.

(2) Runners scoring from second on a single; the norm is 59%.

(3) Runners scoring from first on a double, the norm is 44%.

(4) Batters making outs on the bases, of which there are two basic types, runners thrown out advancing and runners doubled off,

(5) Grounding into a double play vs. double play opportunities, an opportunity being any time there is a runner on first and less than two out,

(6) The Net Gain on stolen bases, meaning Stolen Bases above the level of two stolen bases per caught stealing, which is more or less a break-even percentage, and

(7) Bases Taken

Bases taken had to fight their way through the same kind of edge-definition issues as runners going from first to third on a single. A Base Taken is a base on which the runner moves up on a documented event. Certain baserunning occurrences are documented as defensive failures or offensive accomplishments, but not otherwise documented as a baserunning event. A Wild Pitch or a Passed Ball occurs when the pitch gets away from the catcher, but also when the baserunner is alert enough, aggressive enough and fast enough to get his butt in gear and move along to the next little white square before he is thrown out. It’s a failure by the pitcher or catcher AND a success by the baserunner. Successes and failures are like that in sports; they tend to balance. What one player does, some other player has allowed.

A limited and specific list of documented events, because an unlimited list introduces too many problems of conceptual clarity. Wild Pitches, Passed Balls, Balks, Sacrifice Flies and Defensive Indifference are all situations in which a baserunner moves up if he has the speed and daring to move up, but which are not otherwise documented as baserunning events. OK, Balks are a little bit different, but good baserunners FORCE balks to occur. In 2022 there were 2,486 stolen bases in the major leagues, but 4,385 Bases Taken. The 2023 rules brought baserunning closer to the level of Bases Taken (3,503 steals, 4,594 Bases Taken). It doesn’t make any sense NOT to account for them, and then fill in the blank spaces with speculation.

Nonetheless, as it did for runners going first to third on a single, it took me several years to get them added to the record because a lot of people have opinions about the subject but have no respect for conceptual clarity. We had several years of battles with people who would say “What about if a runner reaches on a single but moves to second base on a throwing error? Shouldn’t that be counted, too?”, or “What about sacrifice bunts?”, or “What about runners moving from second to third on a fielder’s choice, or first to second on a fielder’s choice, or third to home?”, or “What about runners who score from third on a double play ball?”, or “What about a runner who moves from second to third on a fly ball?” Shouldn’t those be counted, too?

Sure; count them. But give your categories sharp edges. In the 1890s, an official scorer had discretion to credit a baserunner with a stolen base if he went from first to third on a single, or in other situations. Sometimes he or she would, sometimes he or she wouldn’t (there were female official scorers in that era, yes). That’s fuzzy-edge record keeping. Define your concepts so that you know what it is you are counting. If you start including things like runners moving from second to third on a ground ball to the second baseman, you’re not balancing the scales by crediting the baserunner’s side of an already-documented event, you’re creating a new category. You’re losing focus, losing conceptual clarity. Go ahead if you want to do that, but try to present the reader with clear concepts which have known parameters.

Though the Handbook is coming to a close, there are resources, such as Baseball-Reference, where you can find this information. Baserunning is too important to be allowed to sink back into a tar pit of speculation. We have done what we could do to replace conjecture with understanding.