By Bryce Rossler

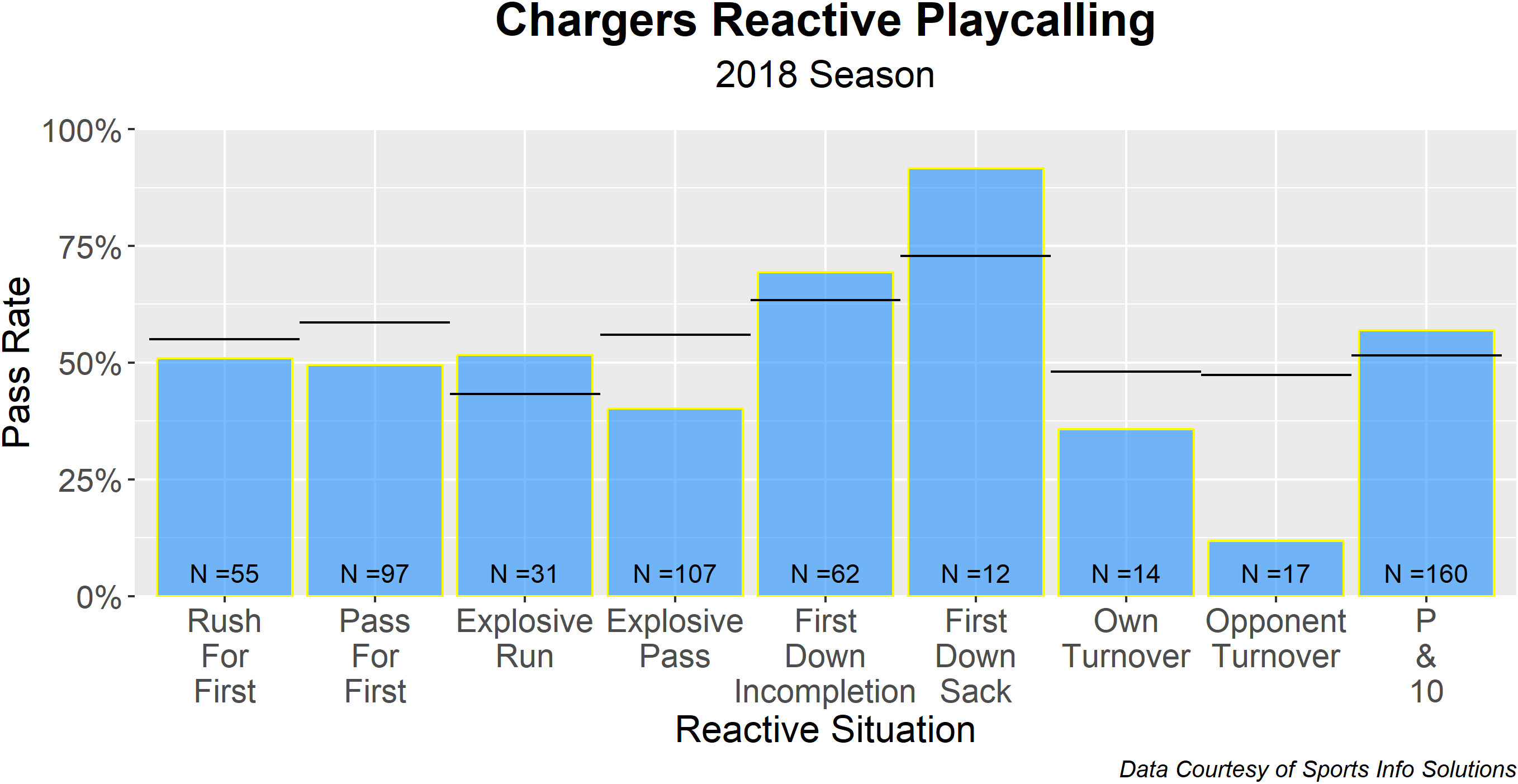

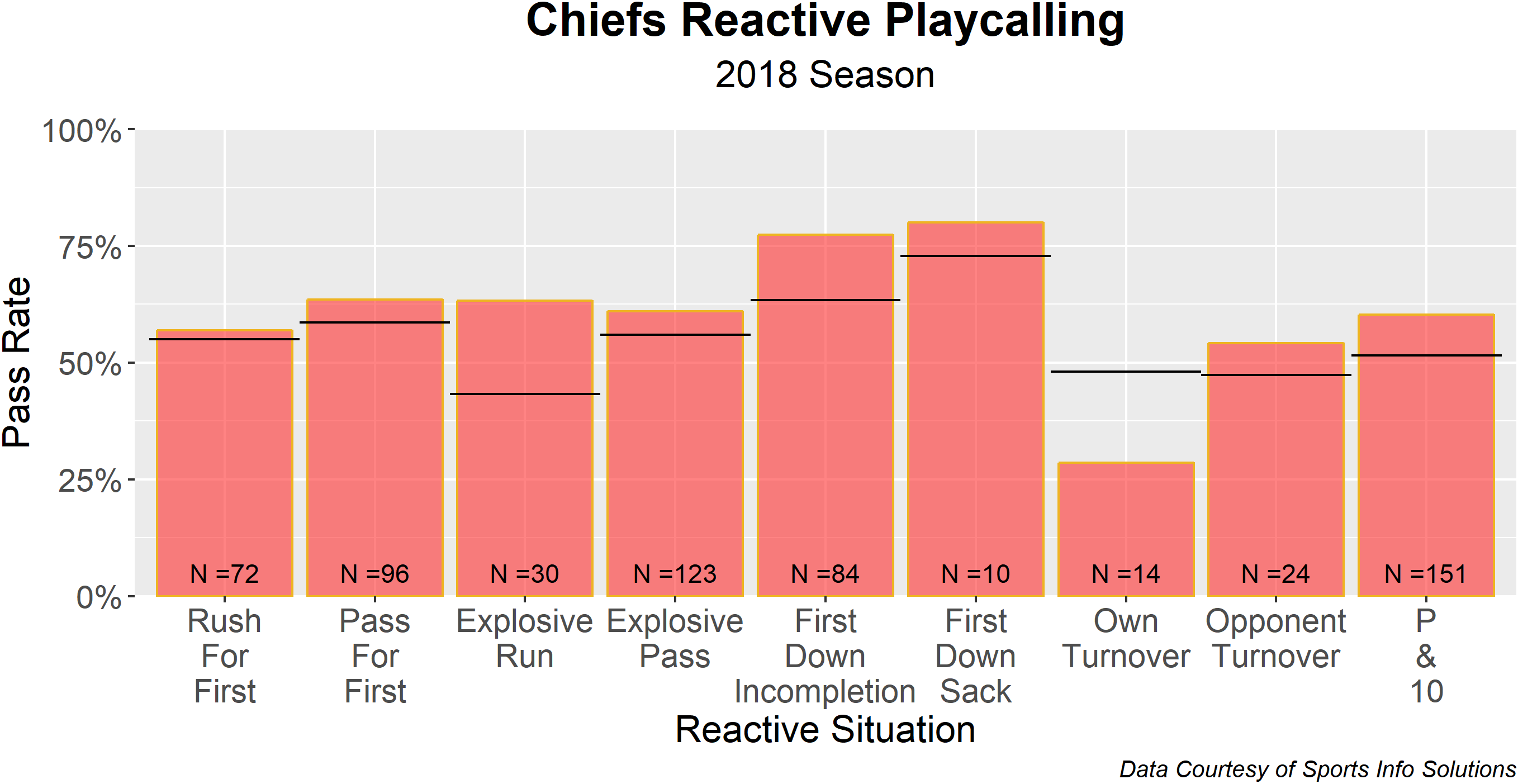

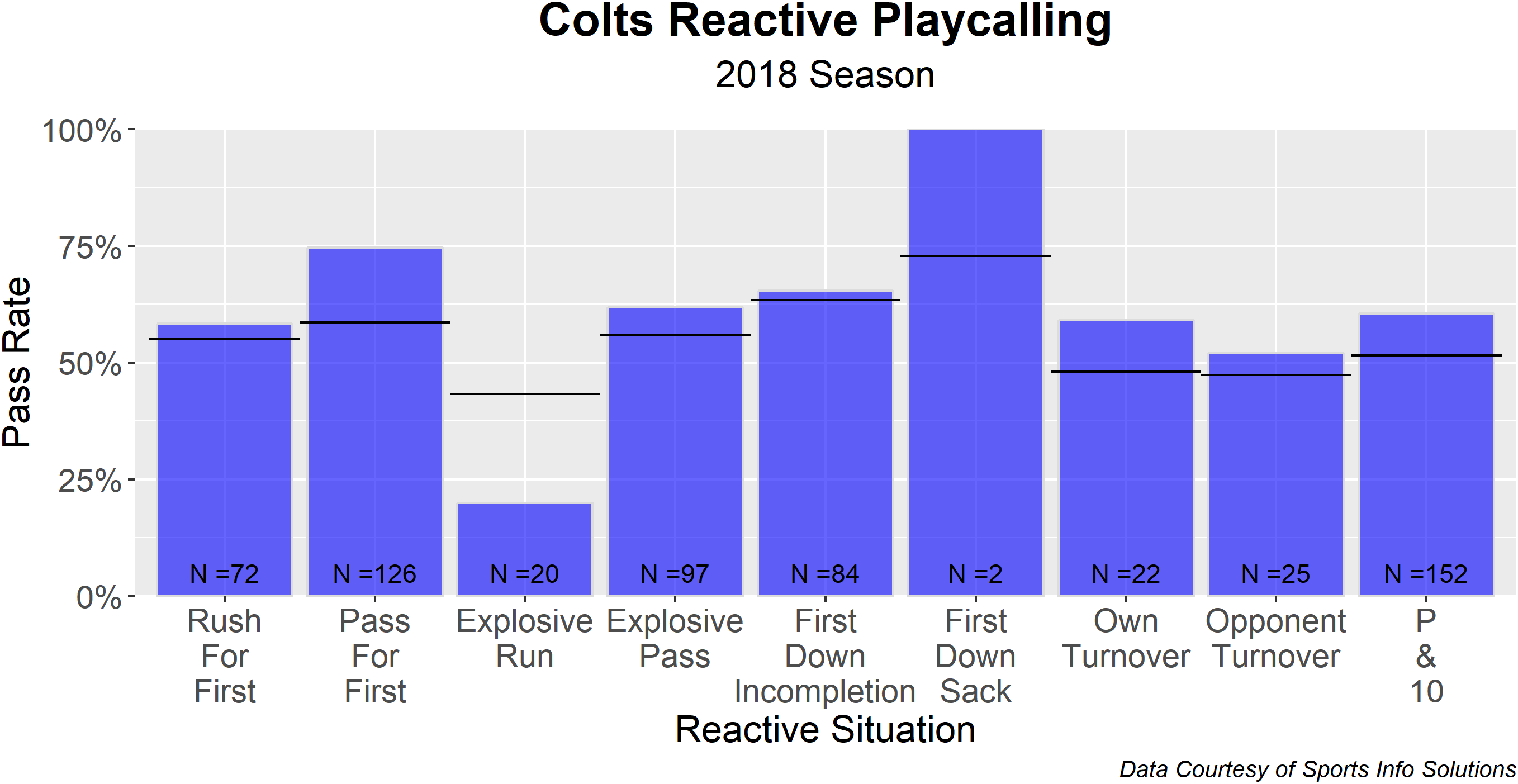

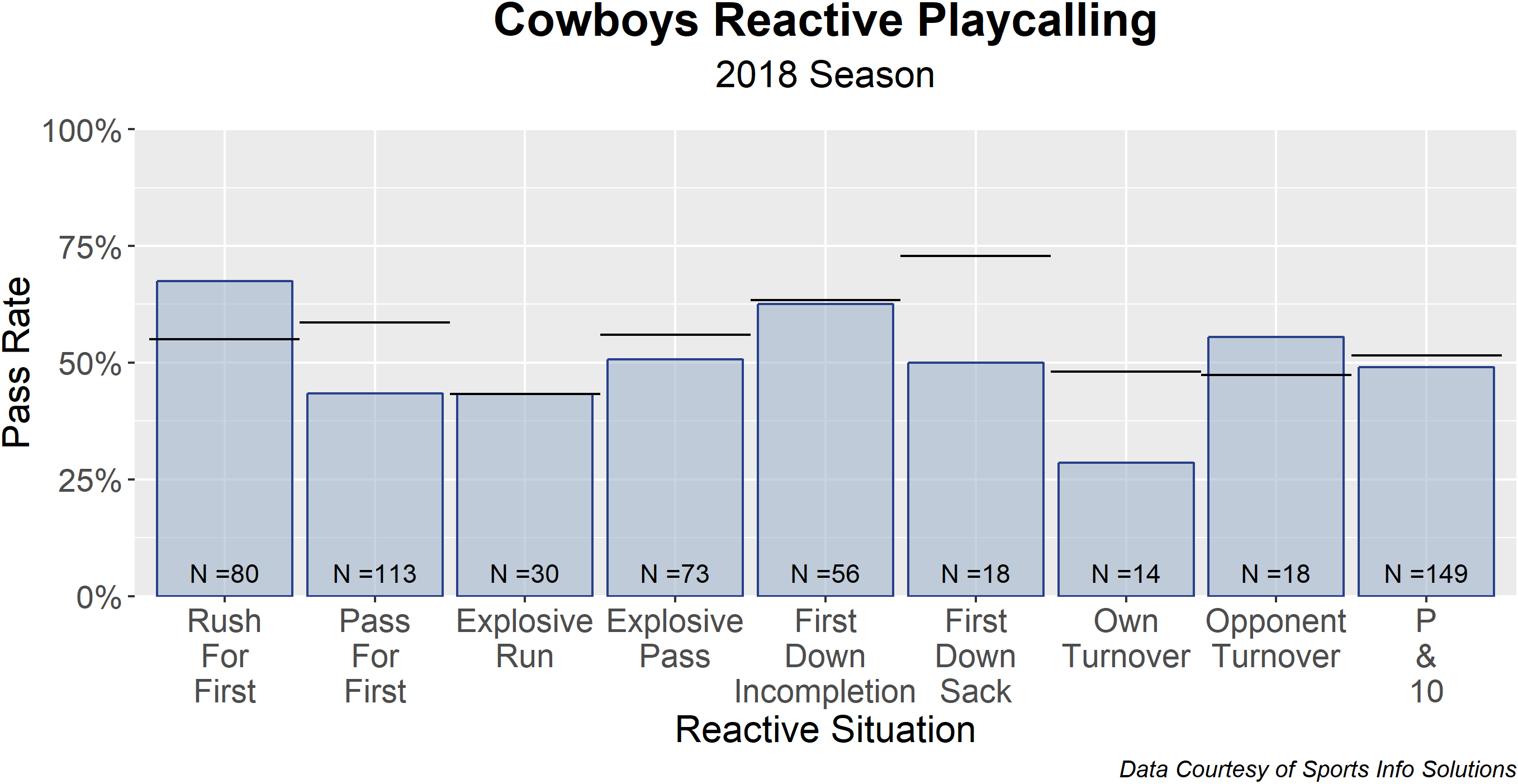

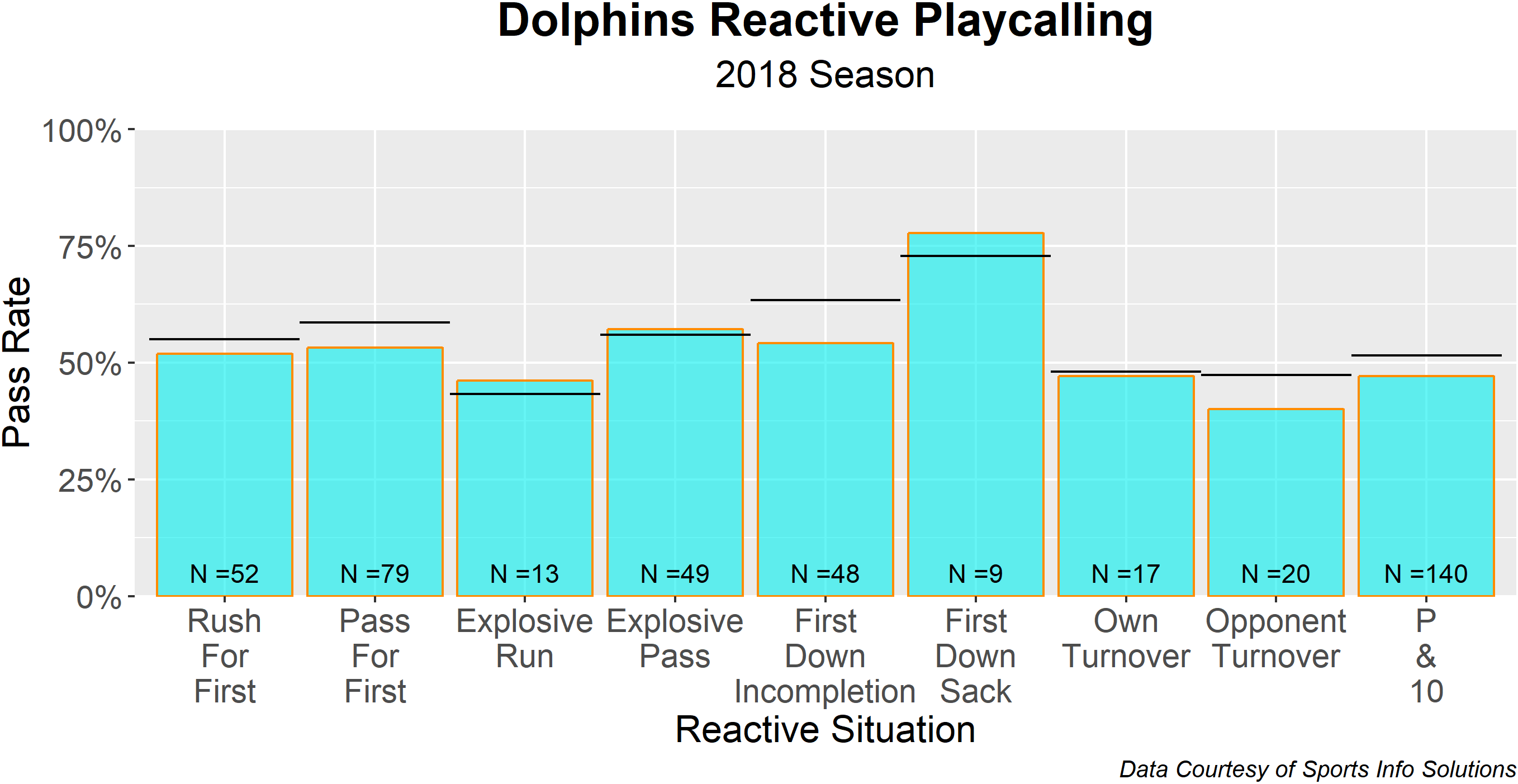

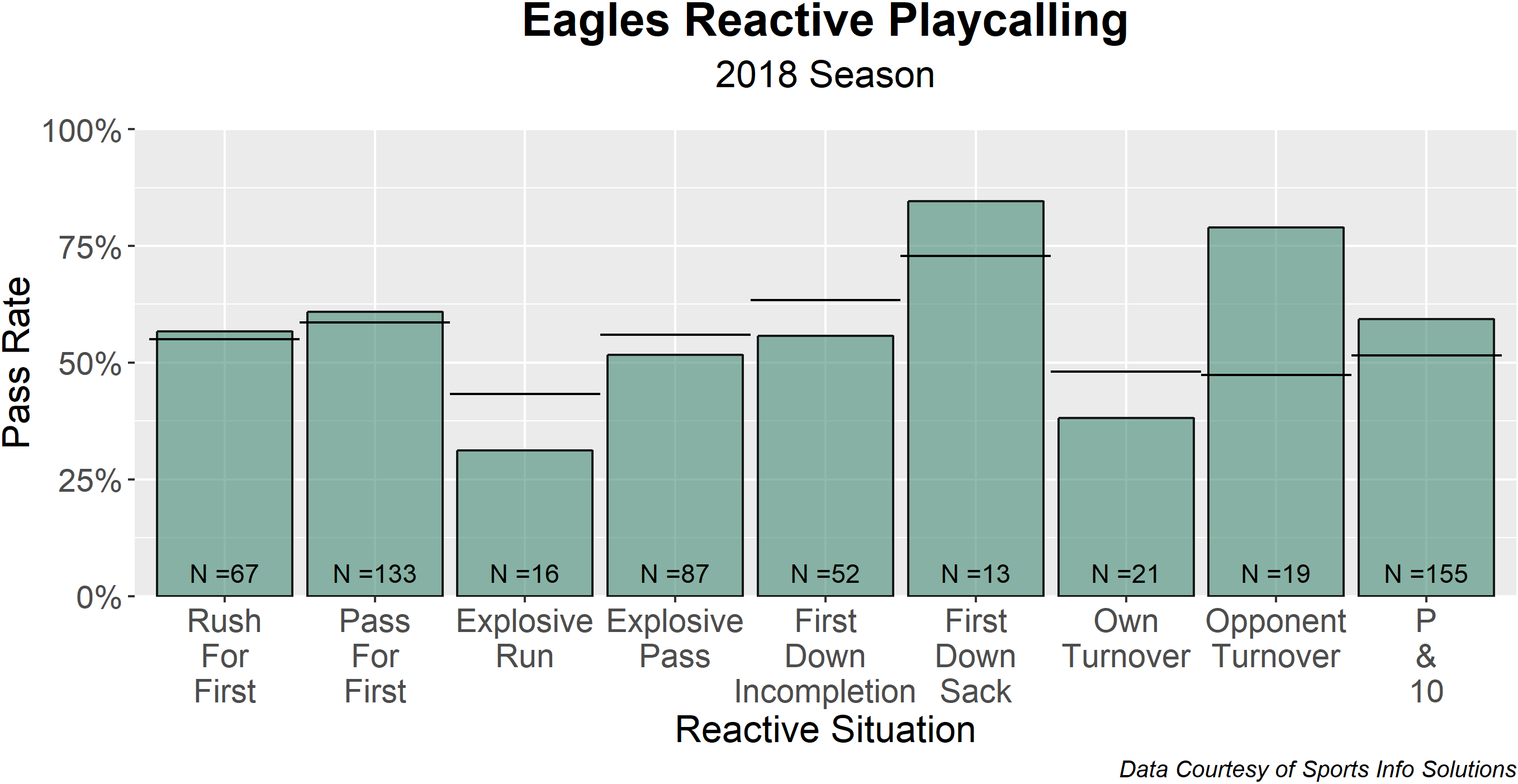

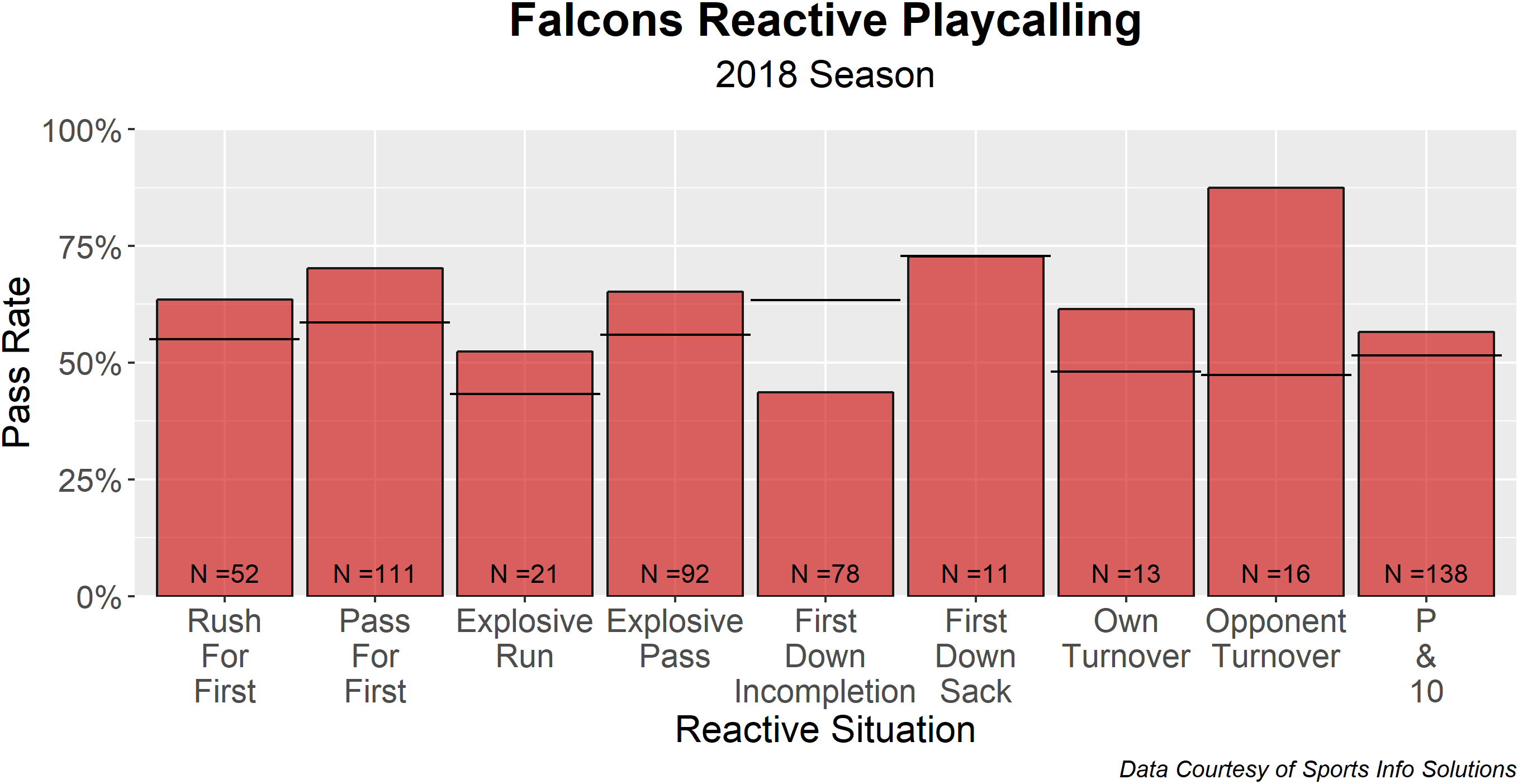

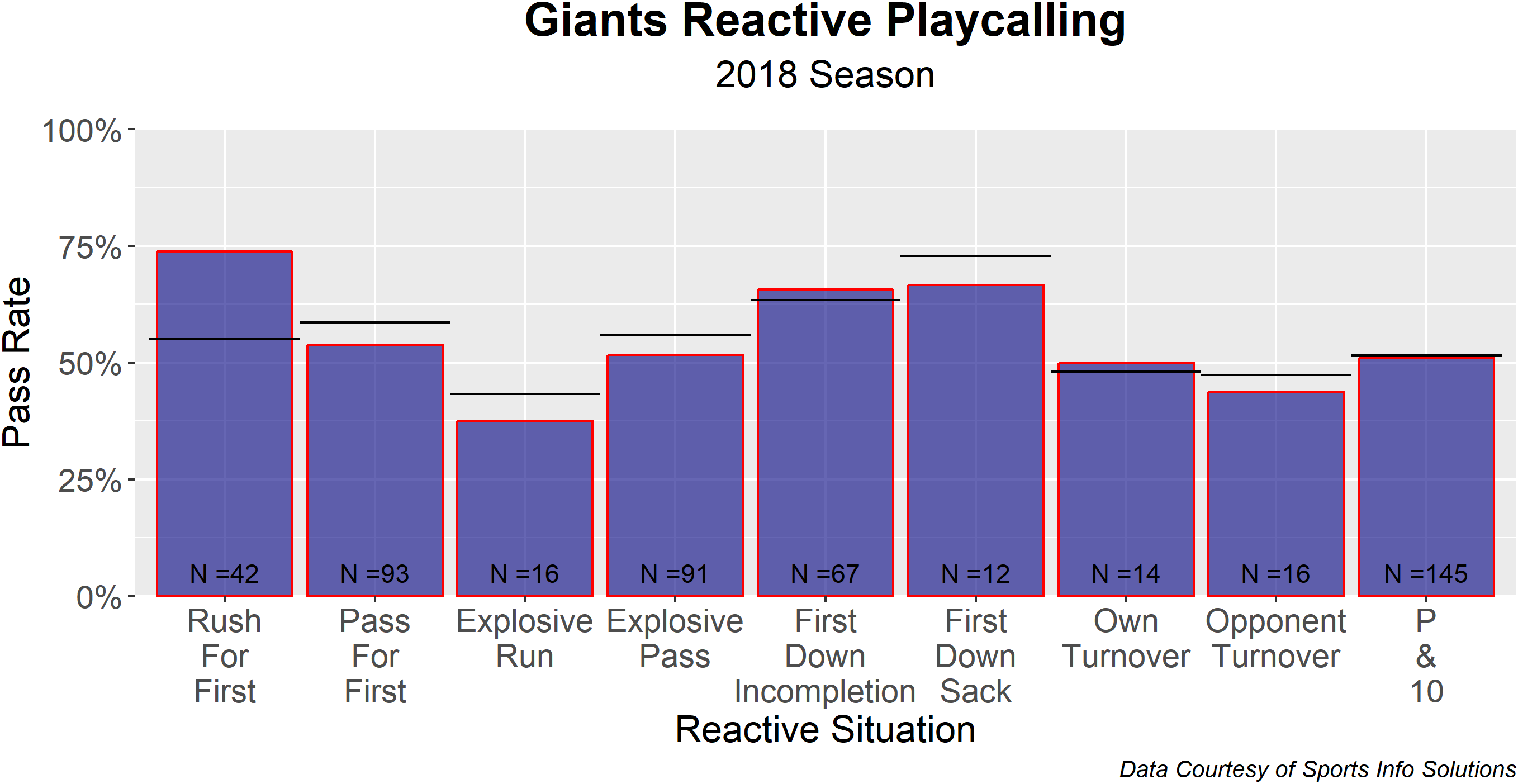

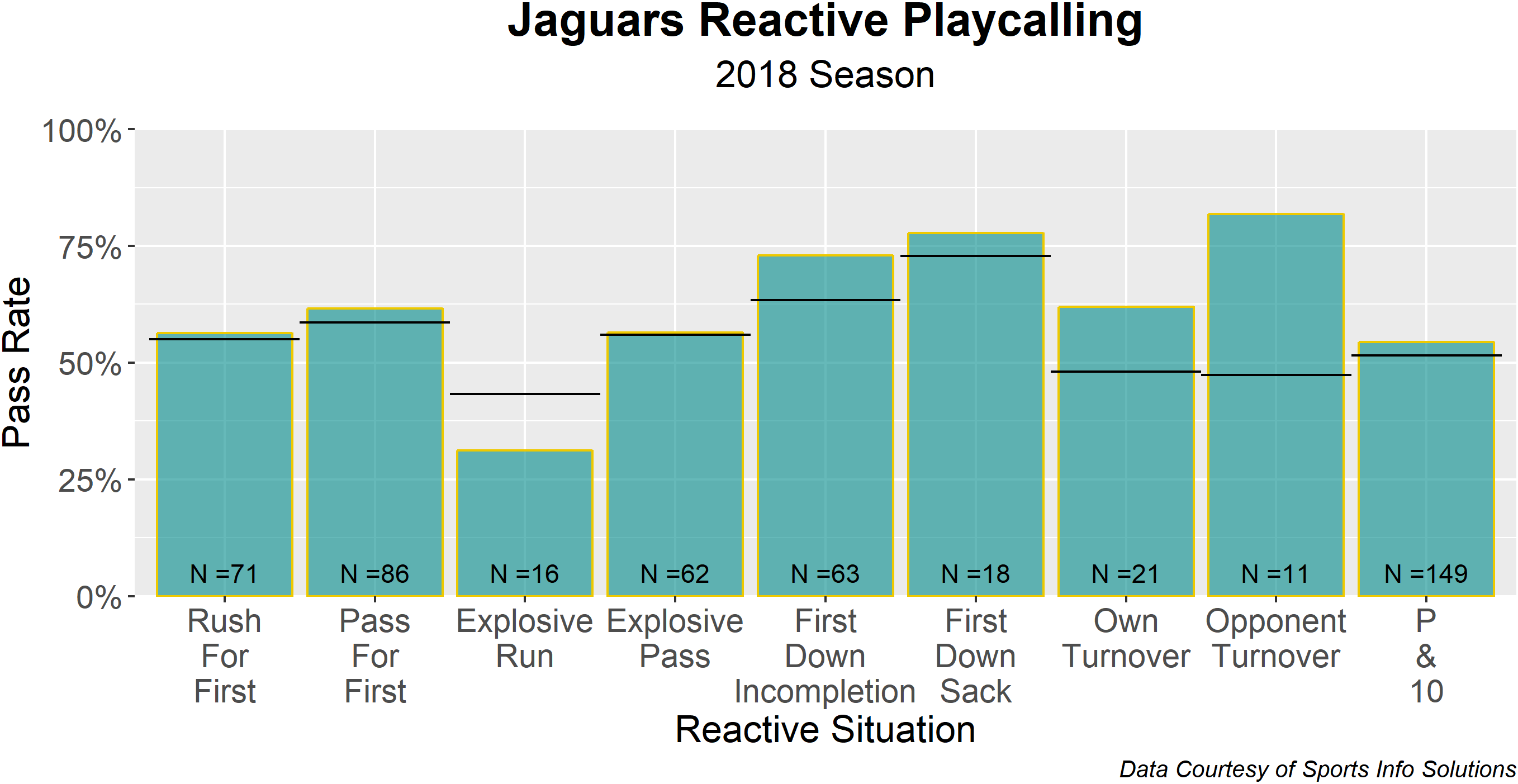

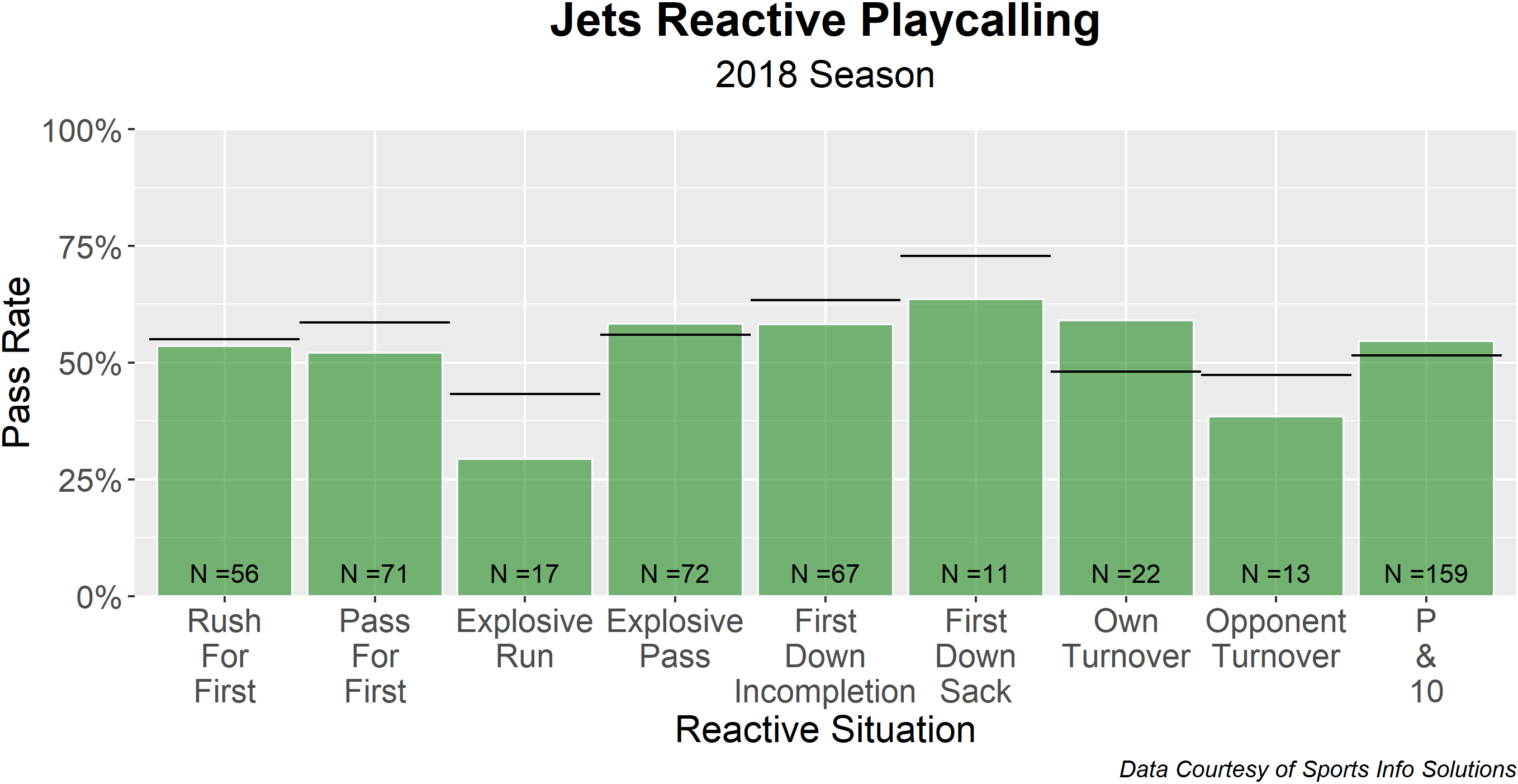

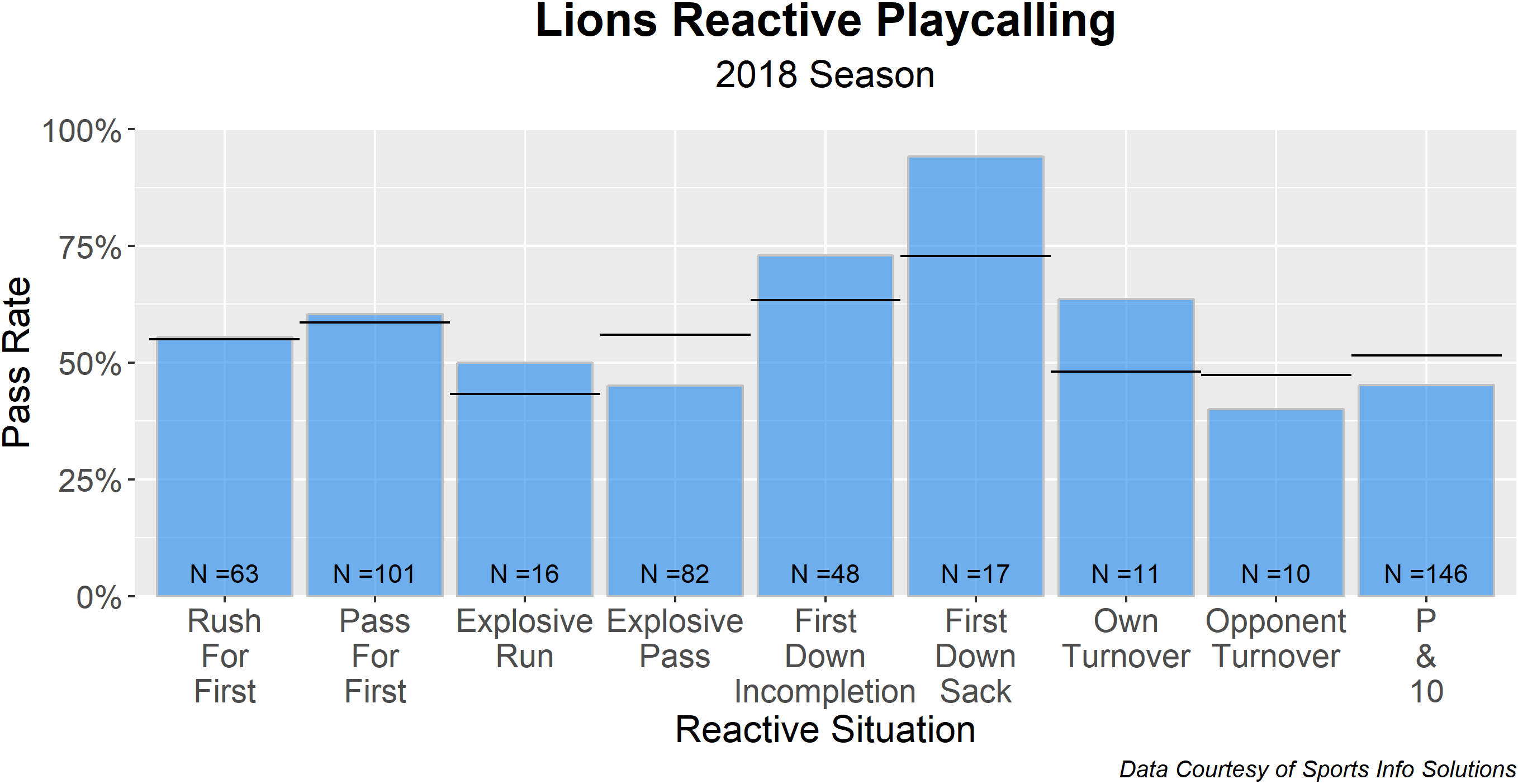

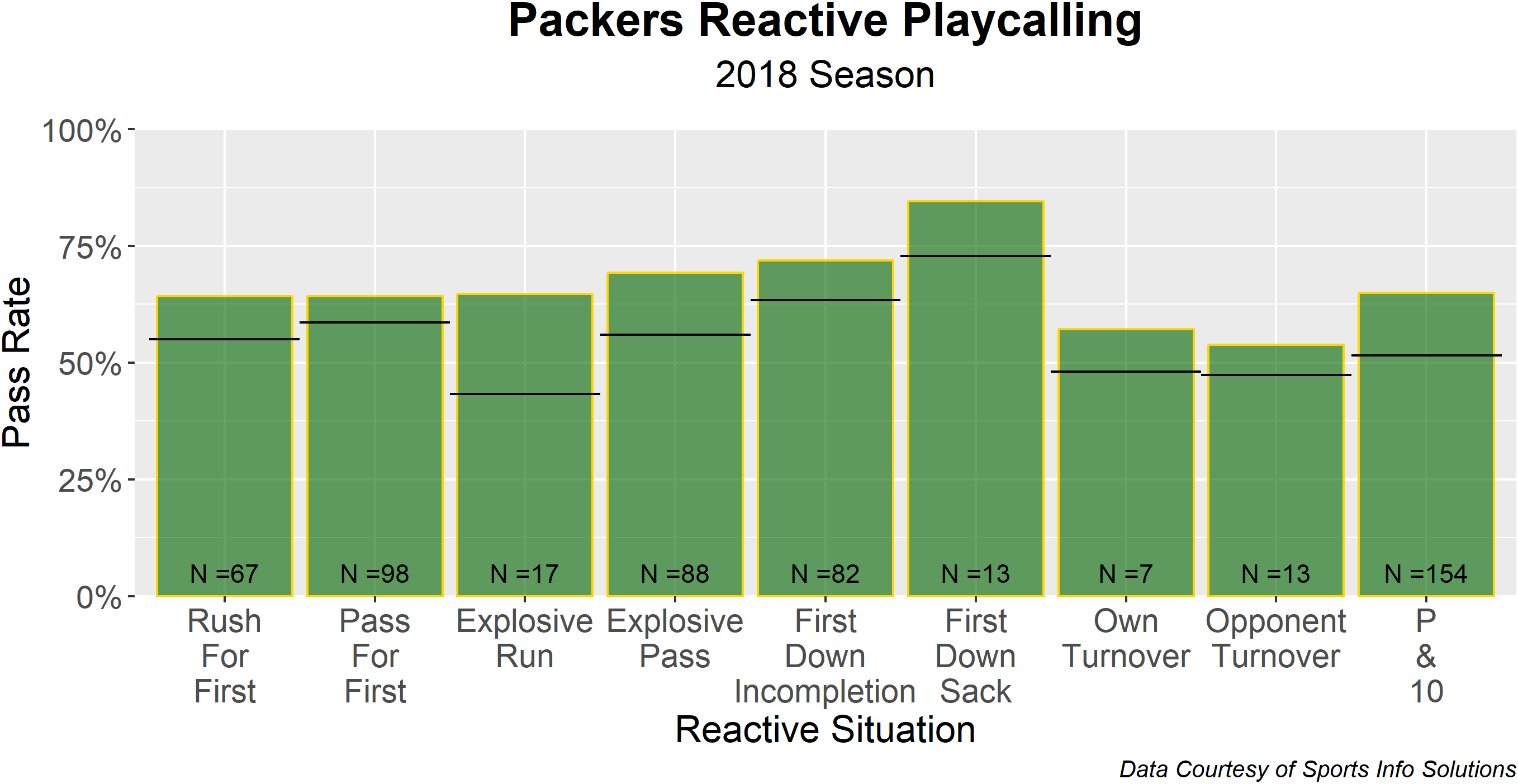

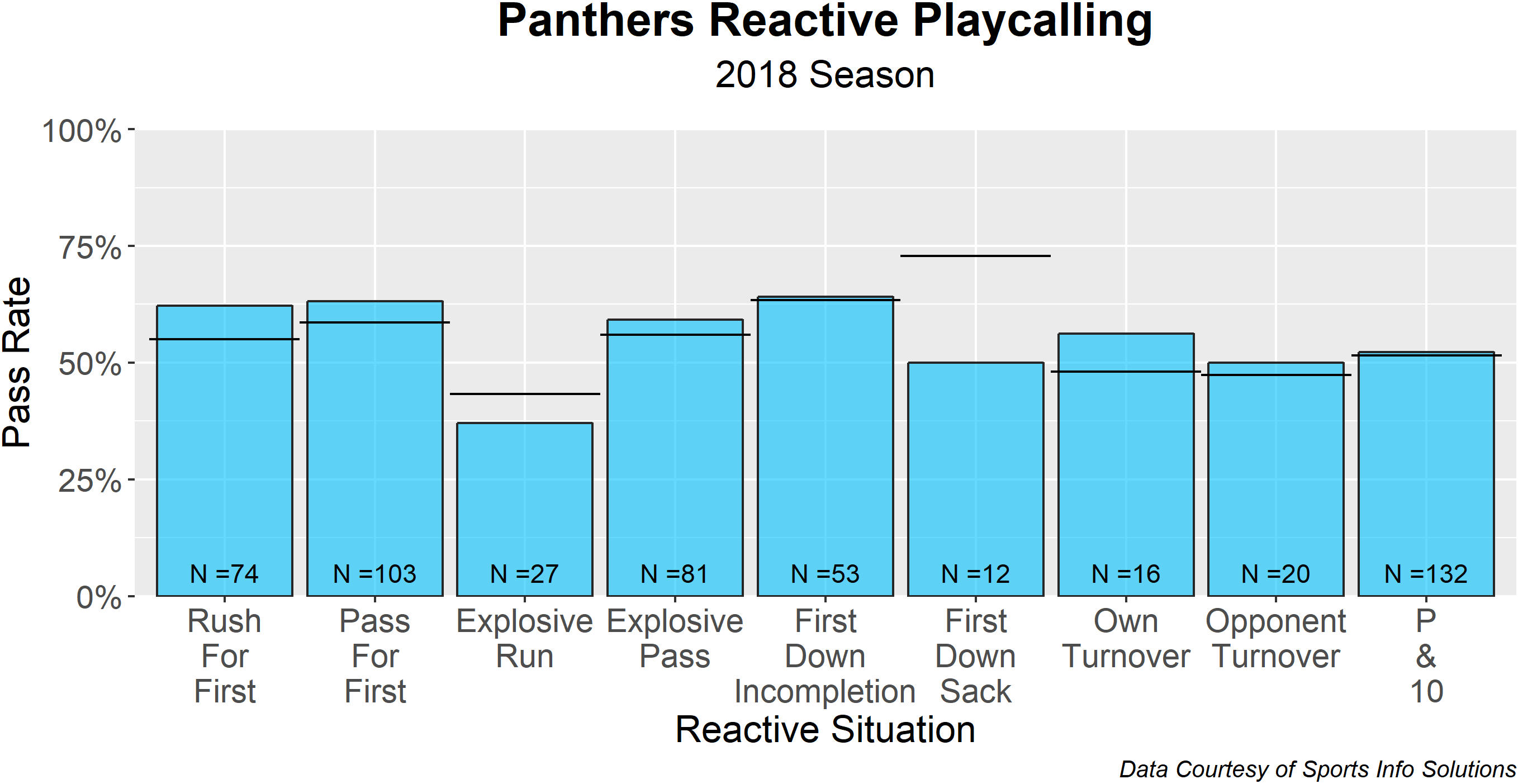

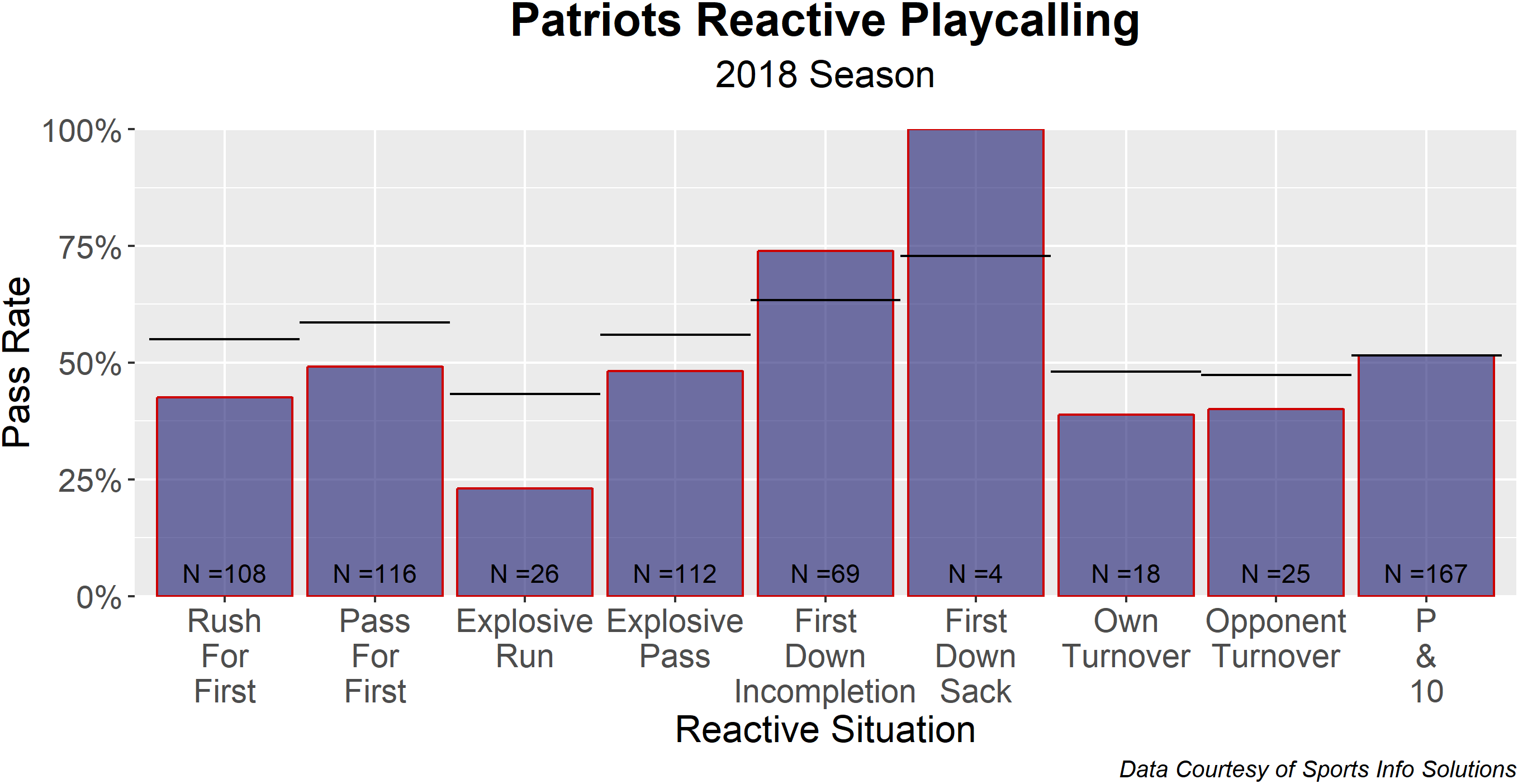

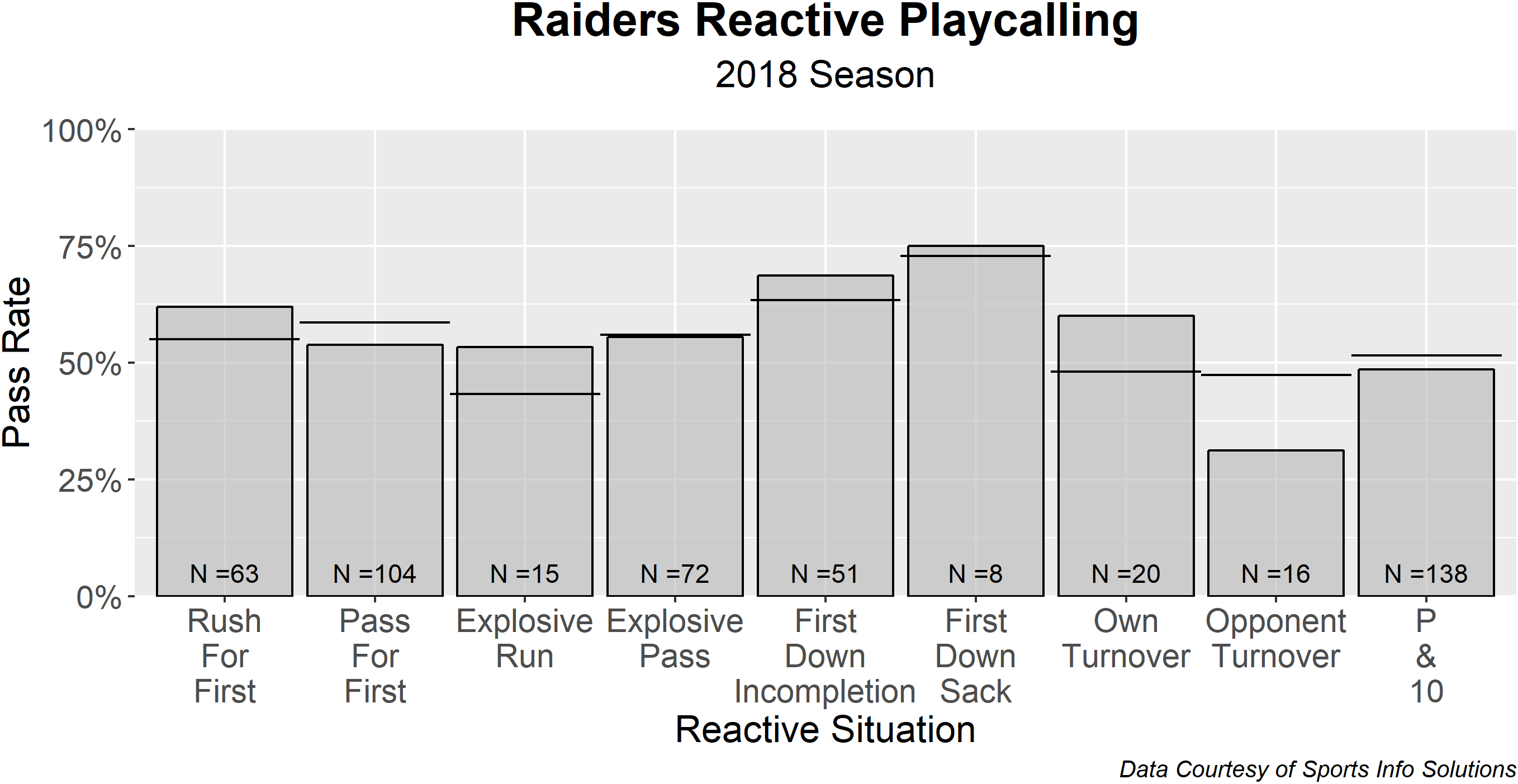

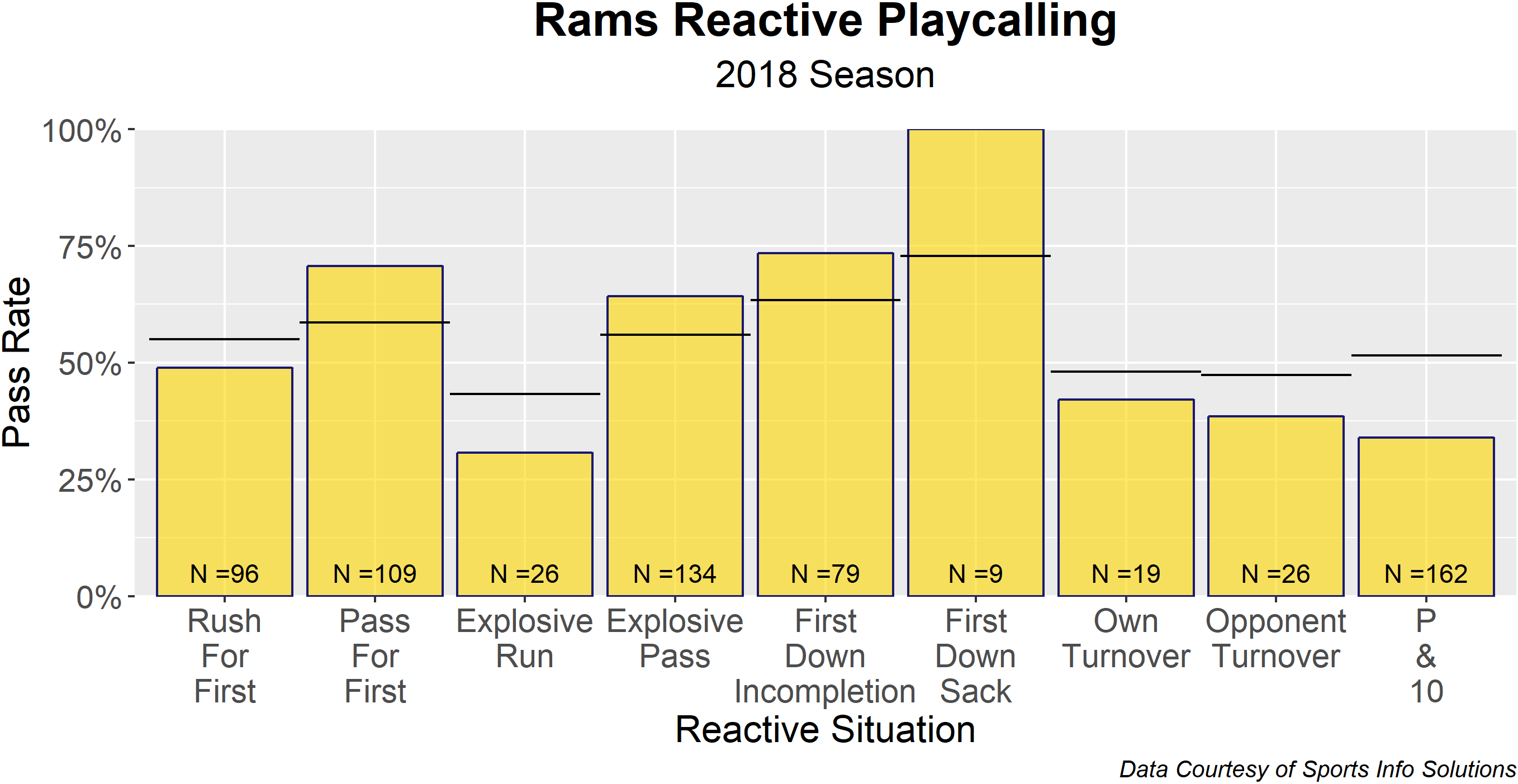

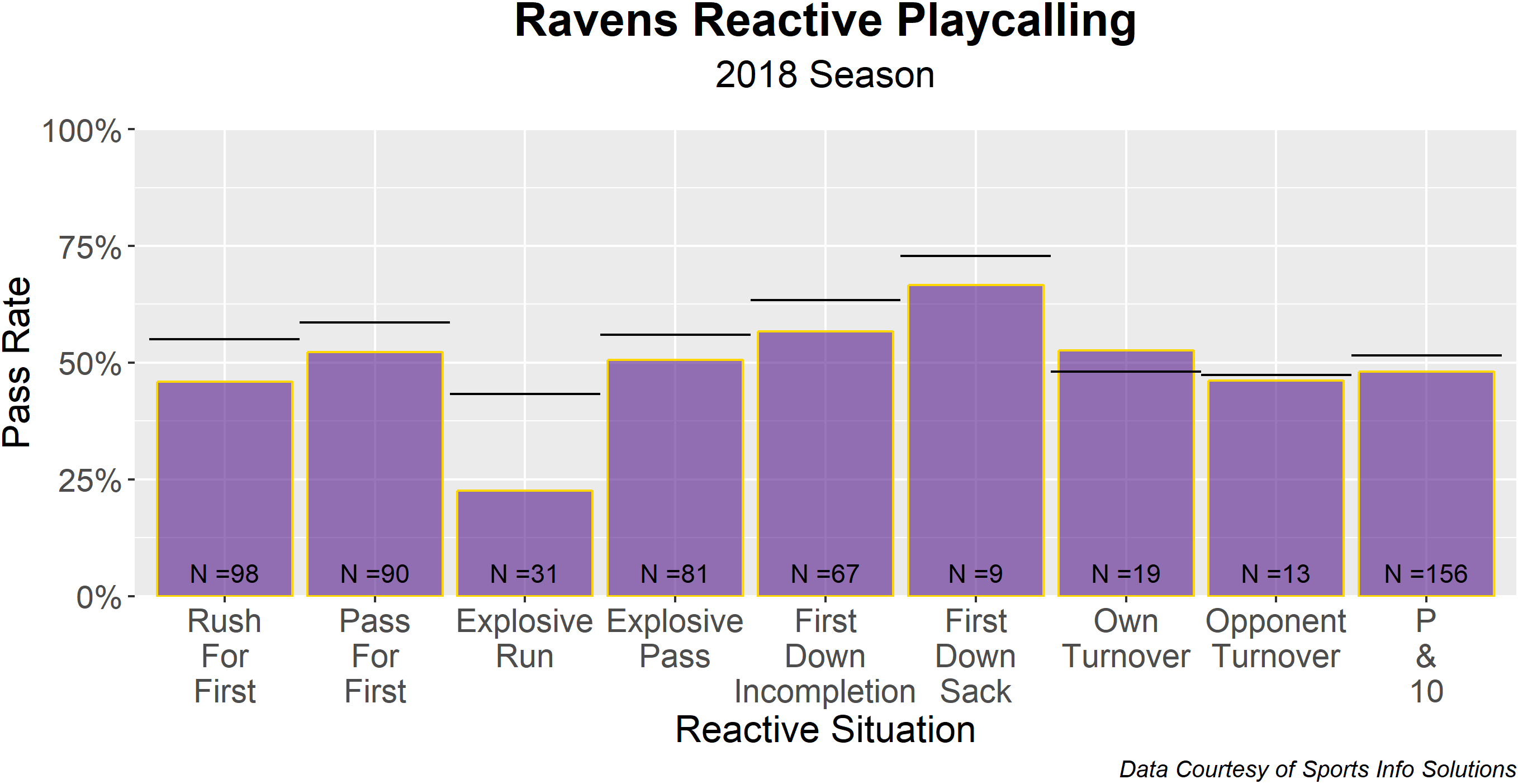

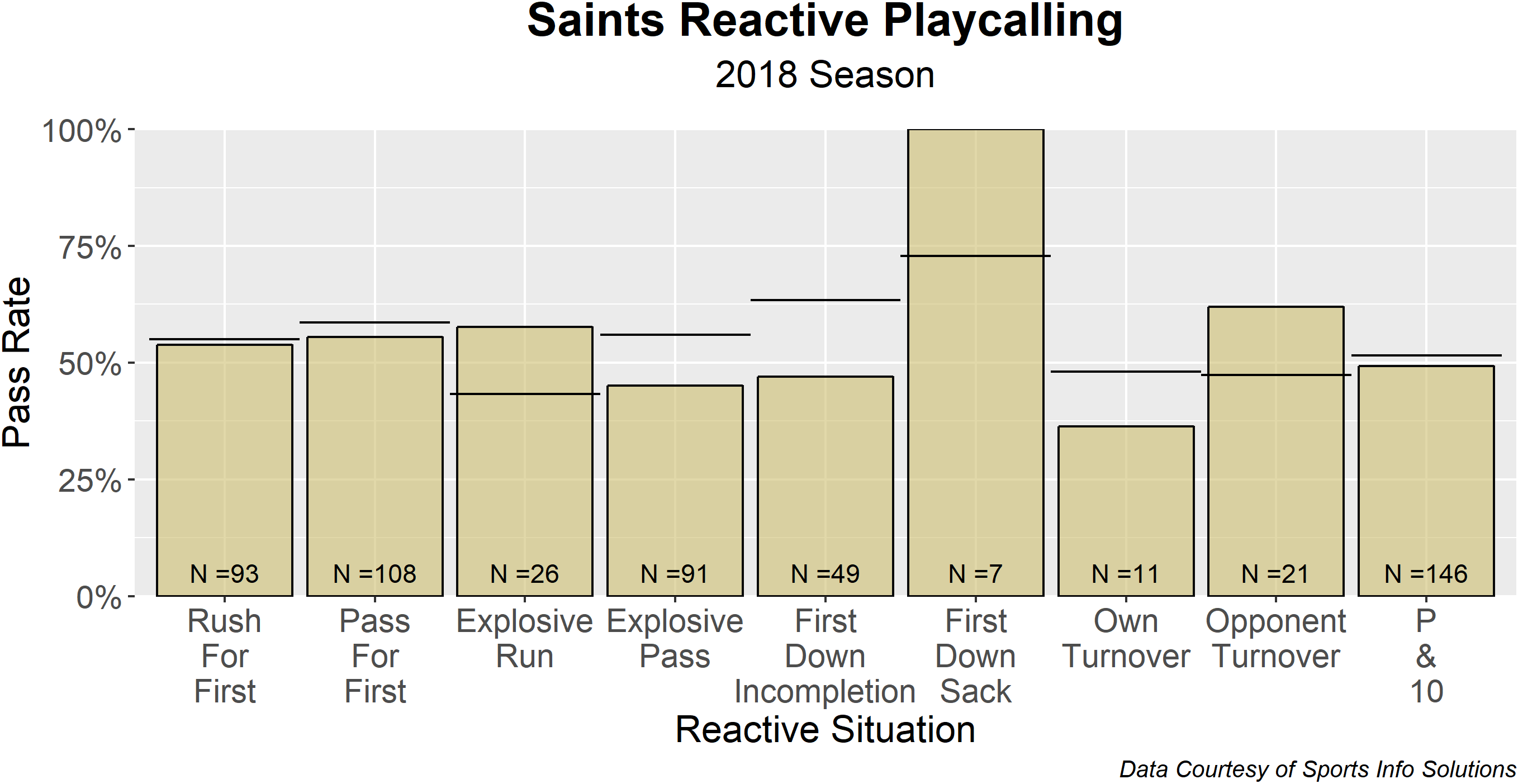

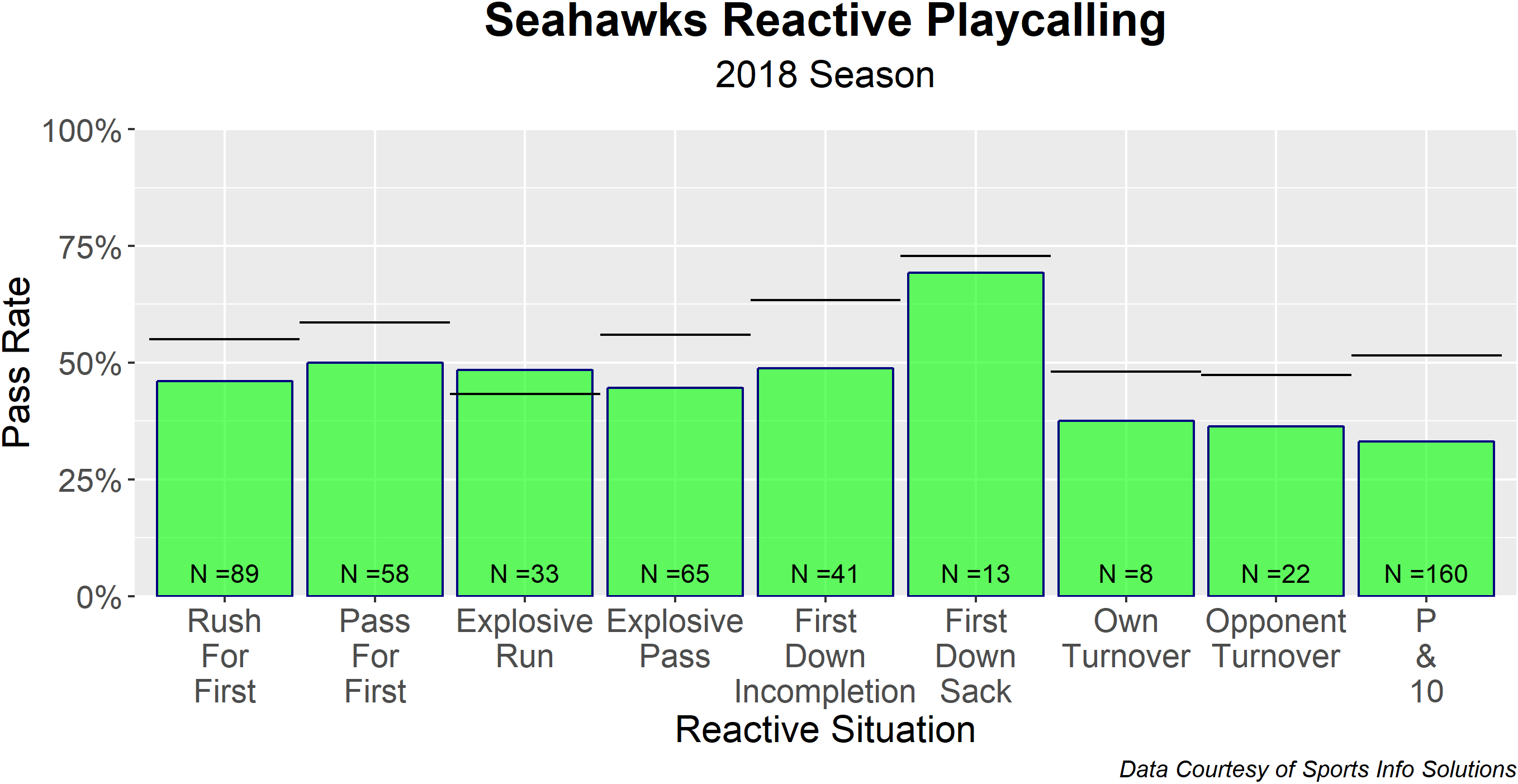

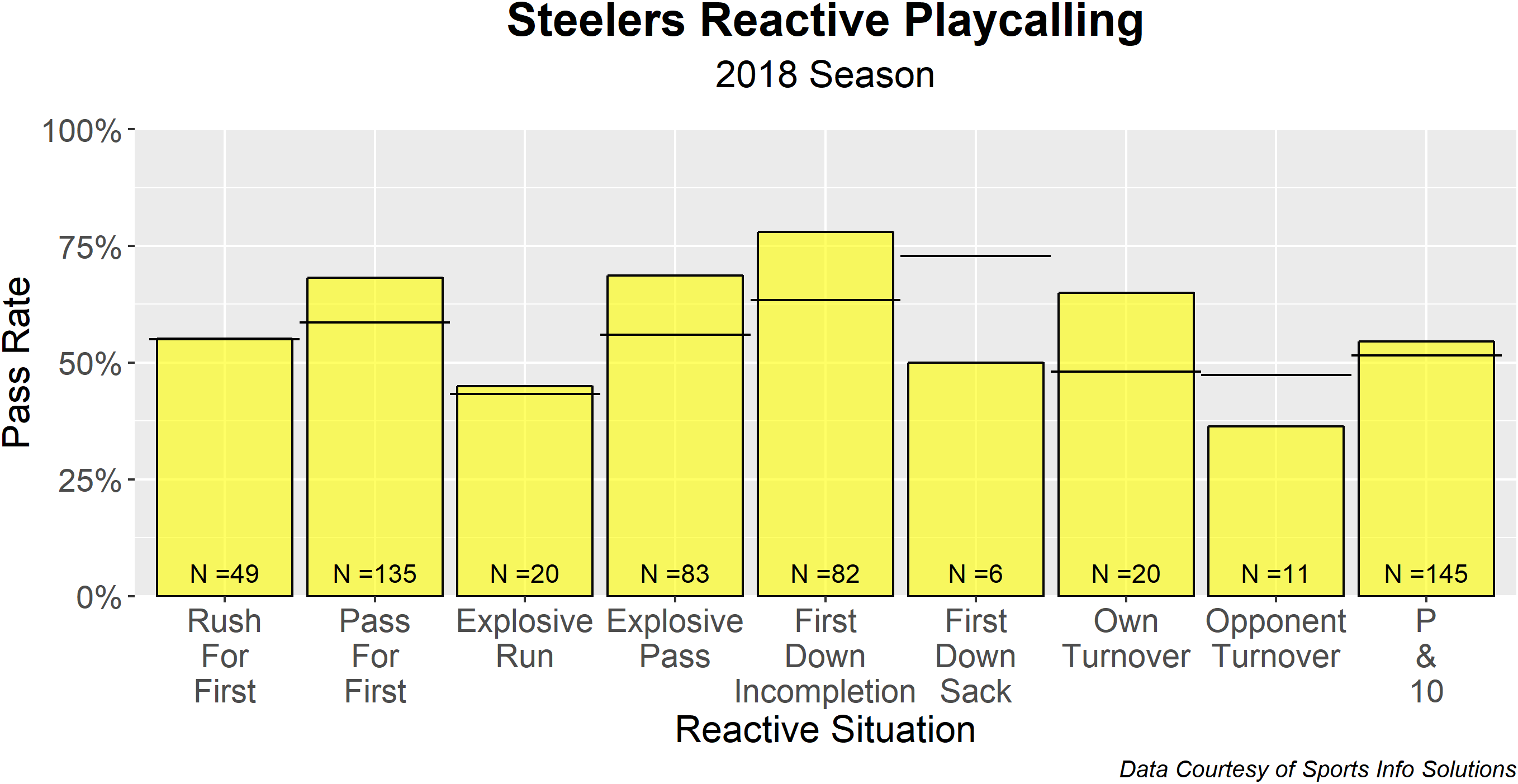

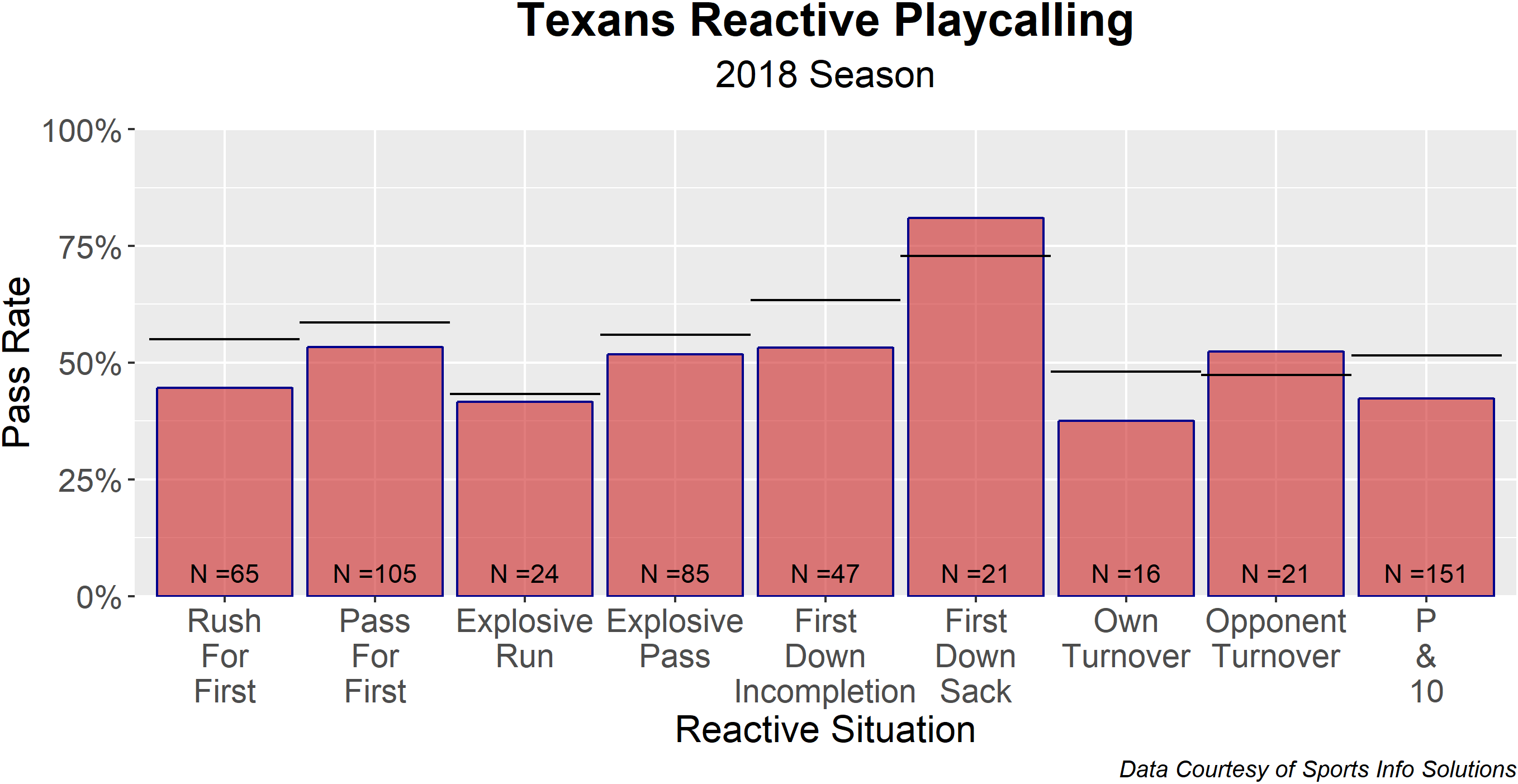

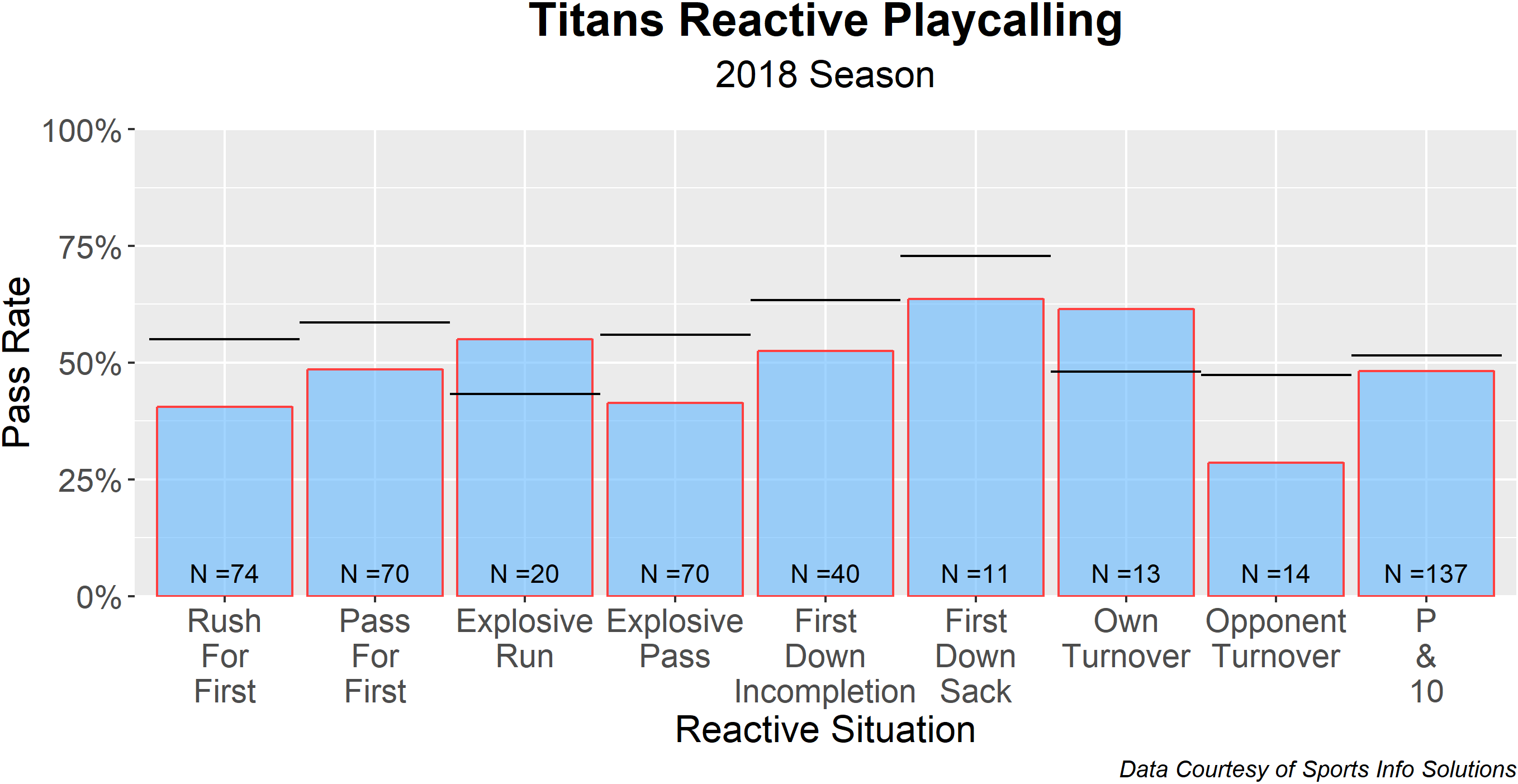

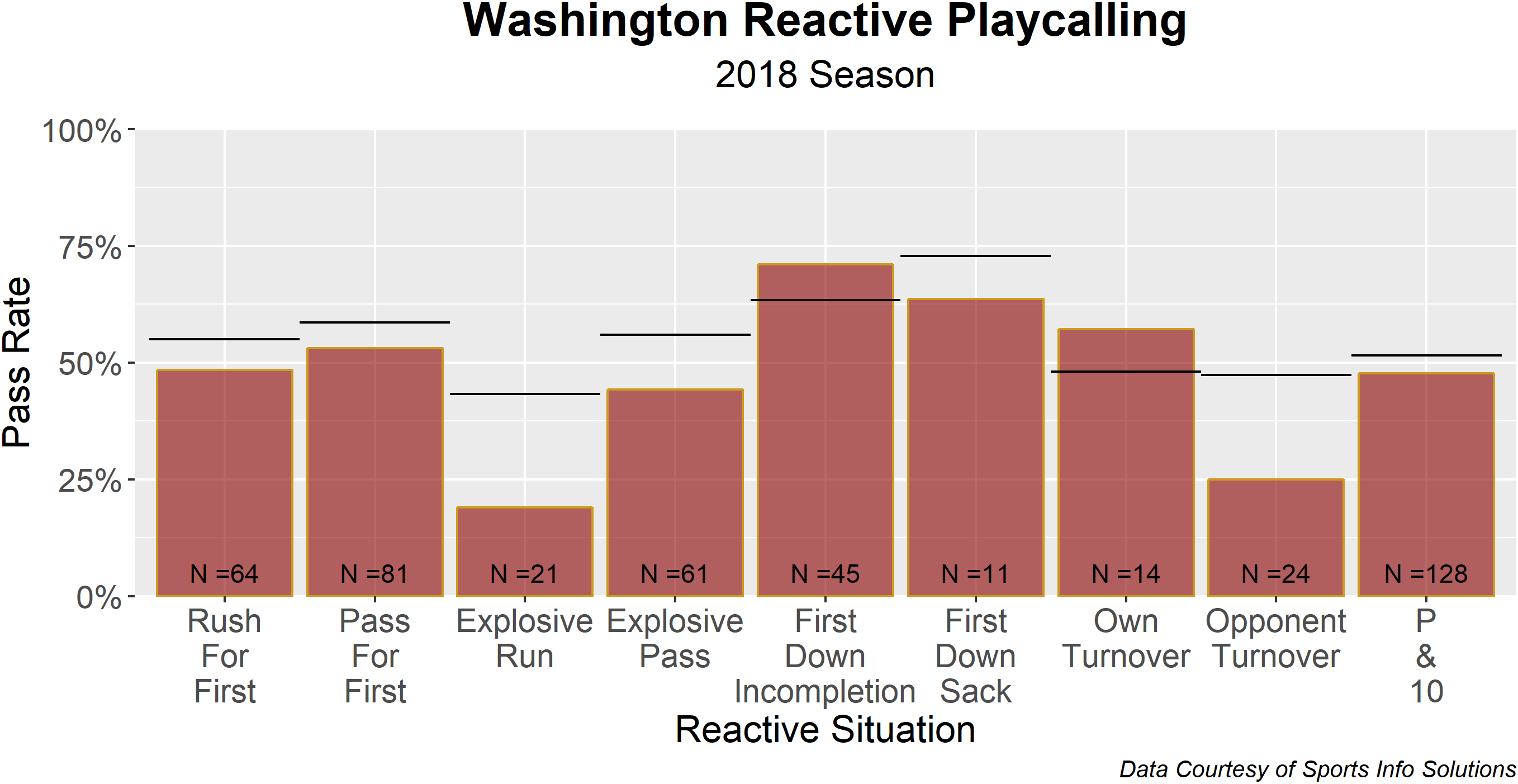

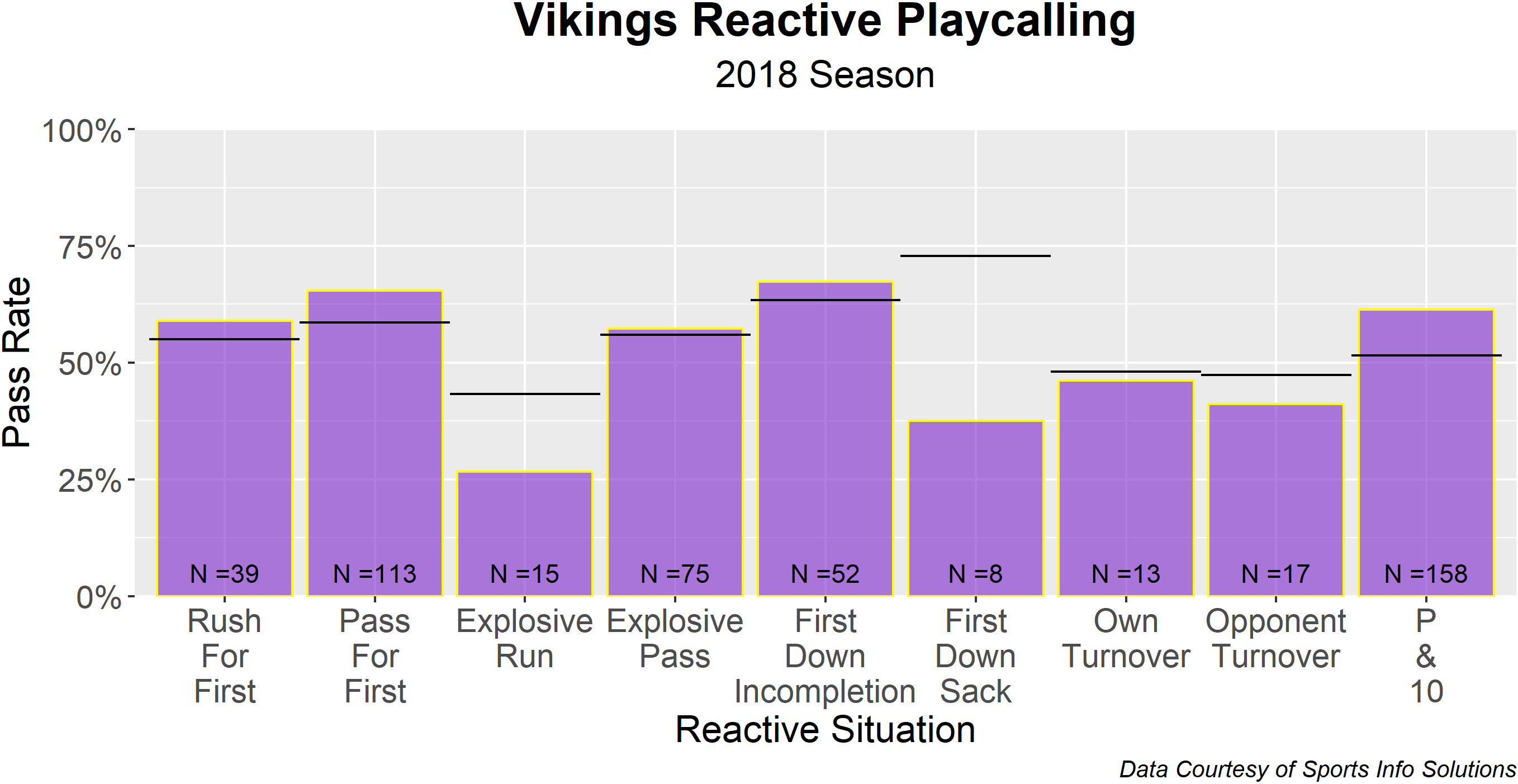

About a year ago, I became interested in the idea of “reactive offense,” a concept invented by Bill Walsh which he eventually detailed in his manifesto Finding the Winning Edge. The late, great 49ers coach was notoriously obsessive in his preparation and believed that it was valuable to understand how playcallers might behave differently following a particular outcome on a play.

“Defensive coaches base much of their game plans on the offensive tendencies of their opponents,” he wrote, “Such tendencies typically evolve from the offense’s reaction to such fundamental factors as down, distance, field position, personnel, situational circumstances, and contingency plans…Collectively, these special plays are commonly referred to as a team’s “reactive offense.”

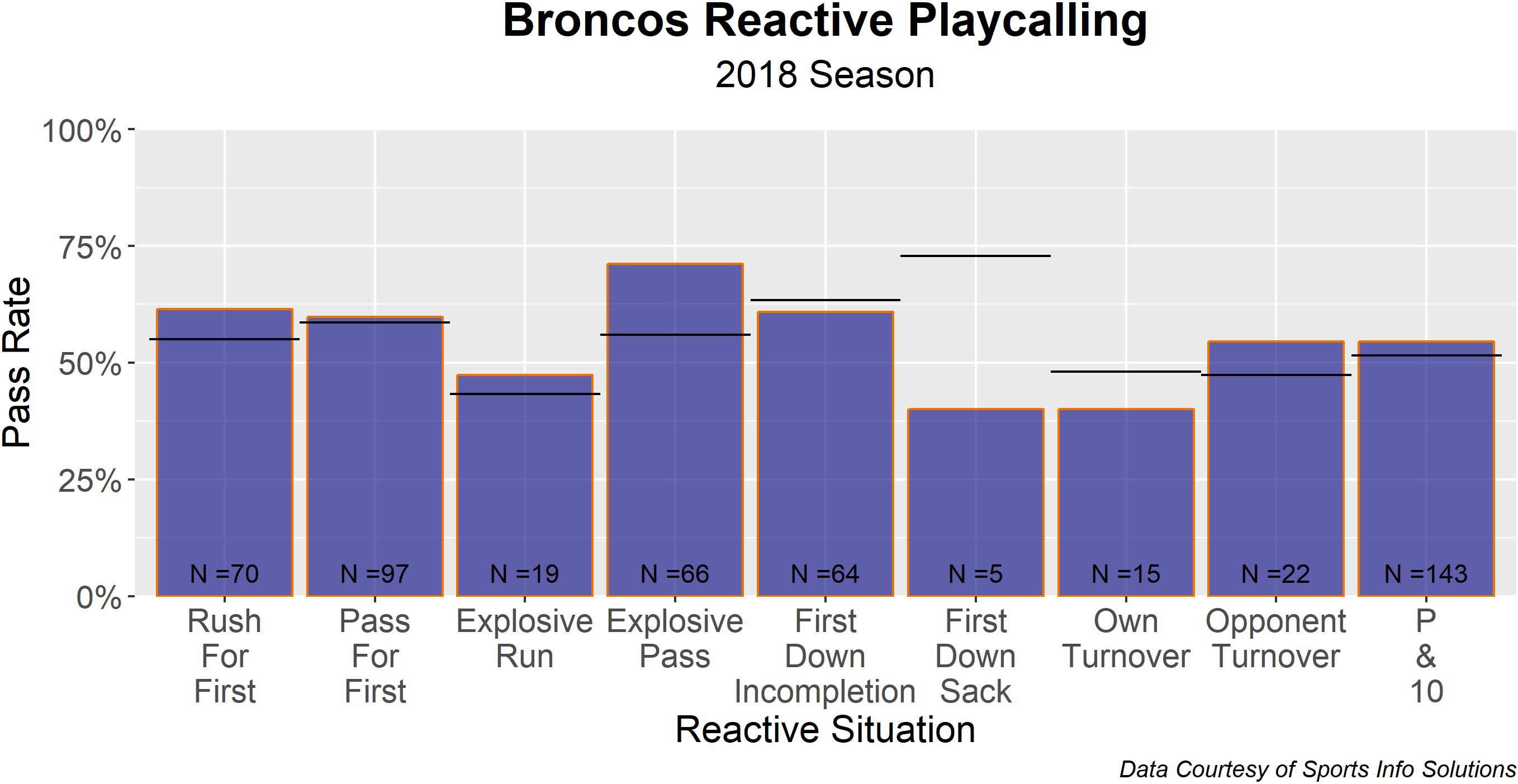

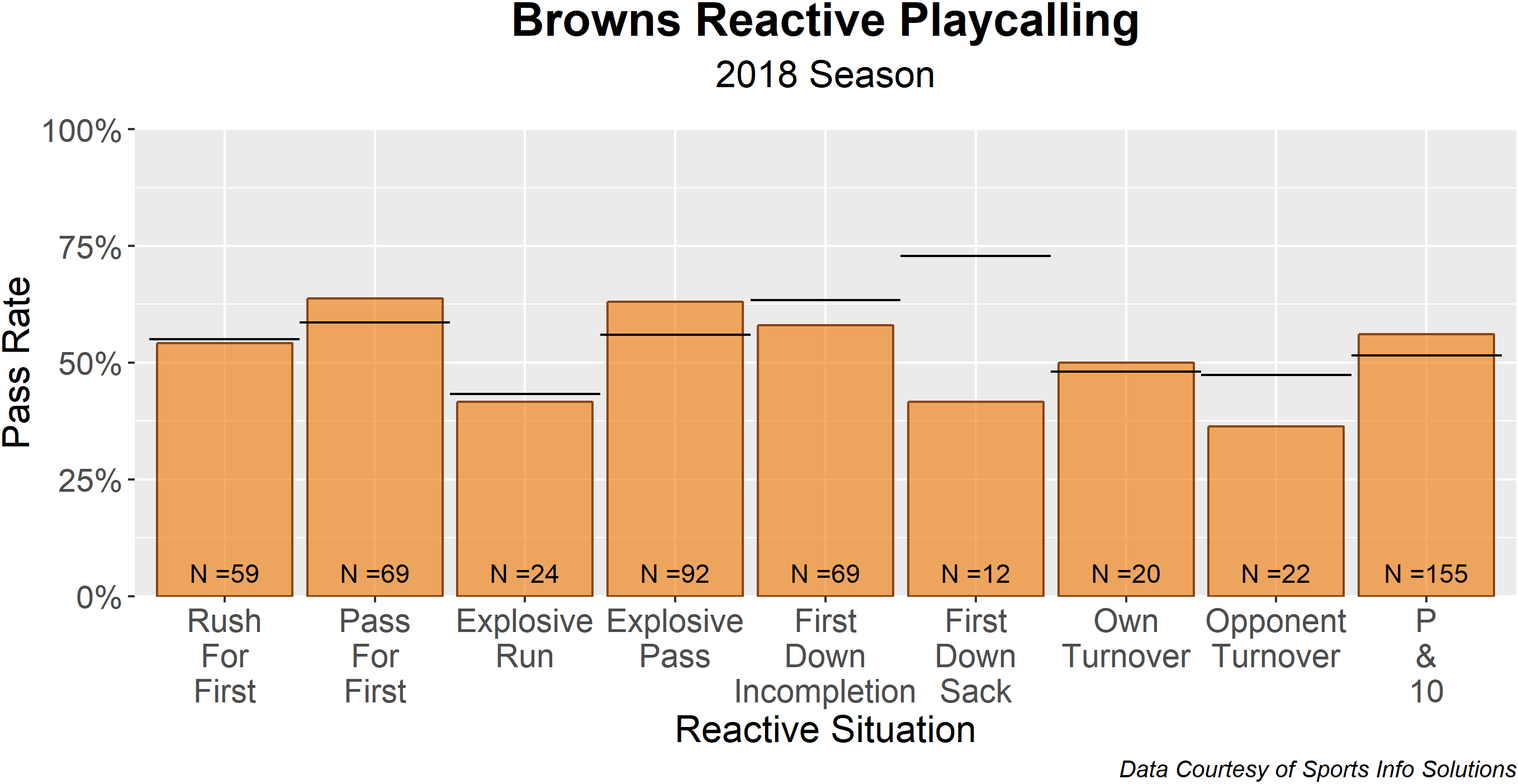

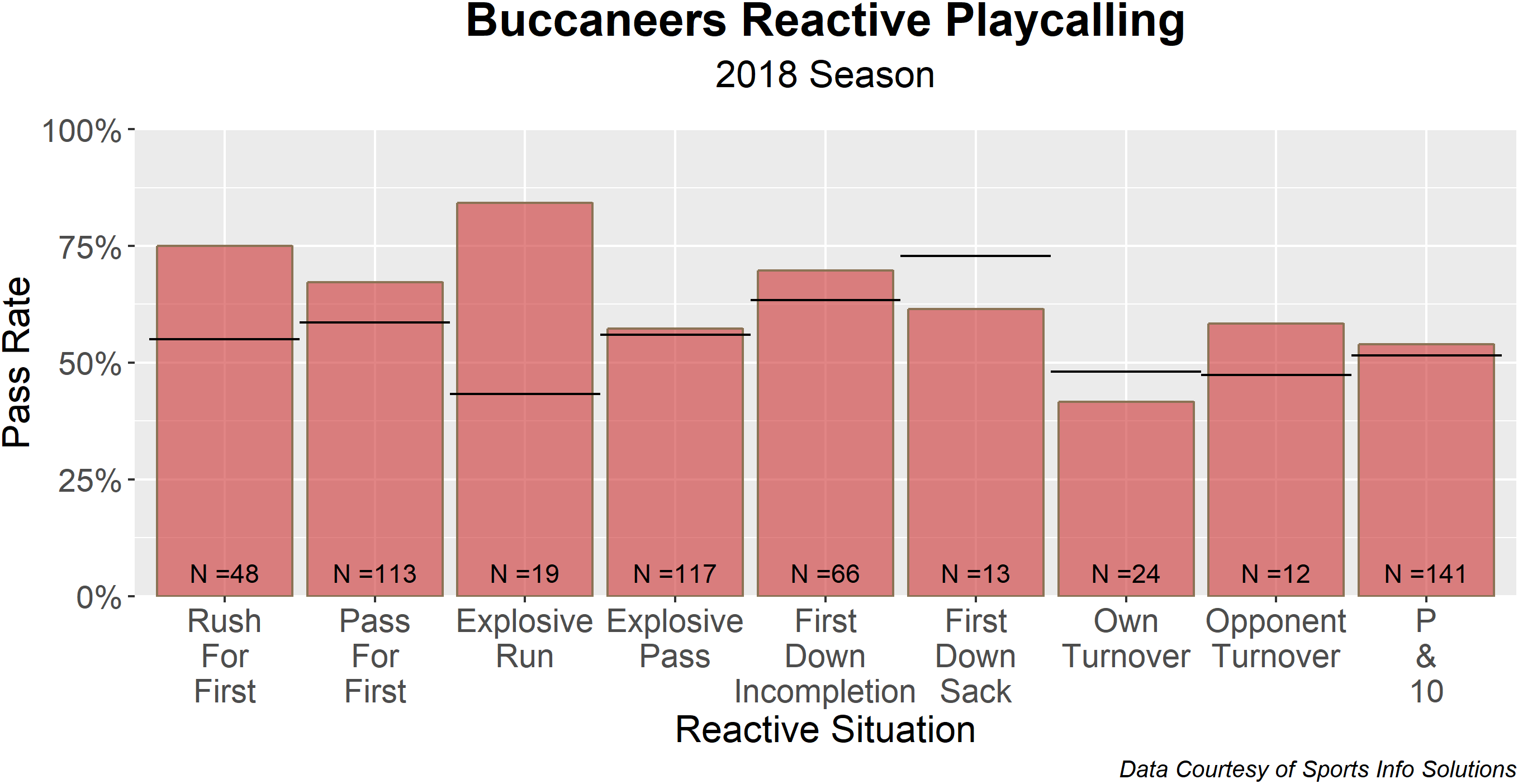

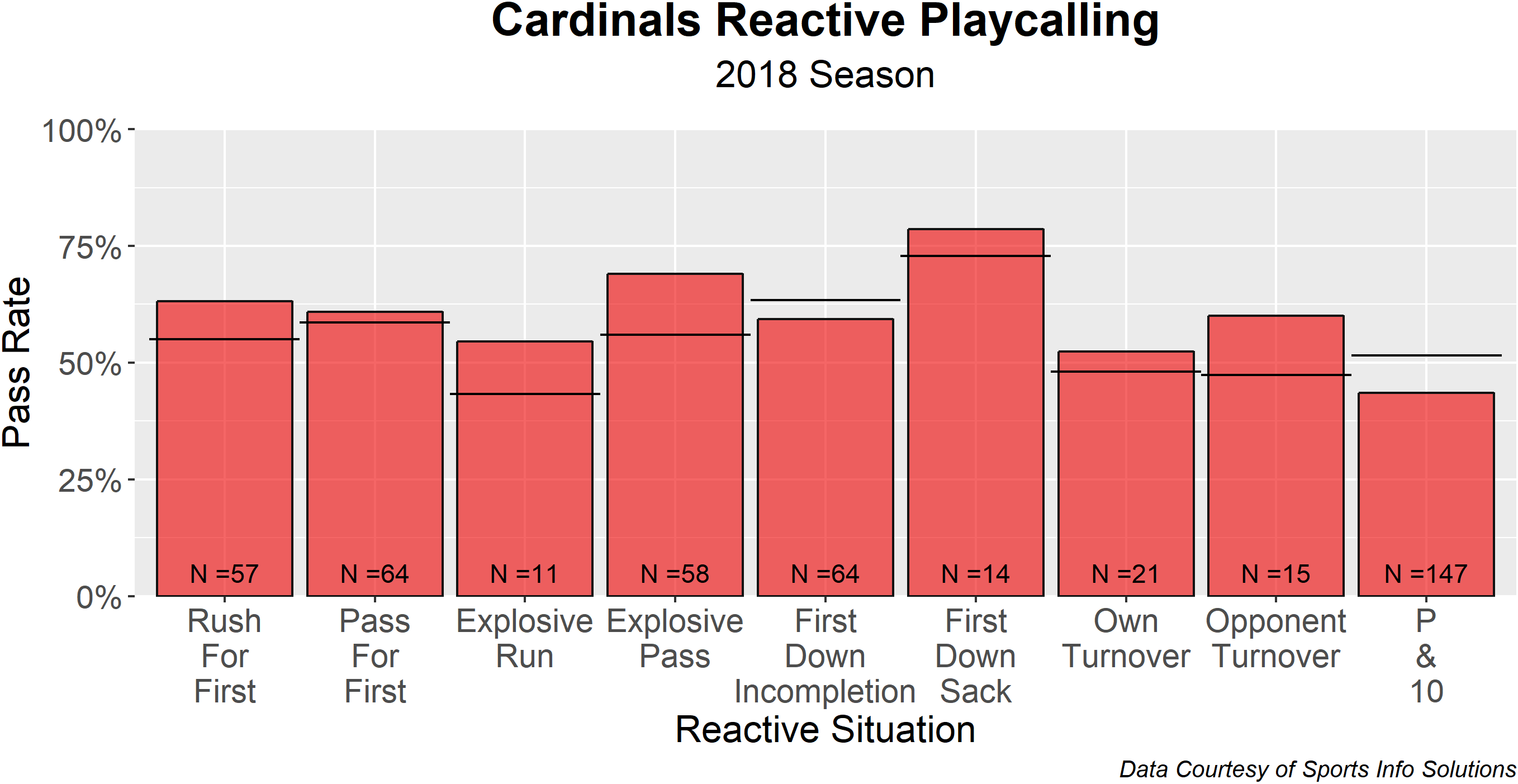

Walsh asserted that the conventional reactive situations were:

- A first down call after getting a first down rushing.

- A first down call after getting a first down passing.

- A first down call after the completion of an explosive pass.

- A first down call after an explosive run.

- A first down call after a positive penalty (i.e., 1st and 5).

- A second down call after a sack.

- The next first down call to start a series after your team has lost the ball on a fumble or interception.

- A first down call to start a series after your opponent’s loss of a possession due to a turnover.

For the purposes of this piece, we will not examine first down calls after a positive penalty. Instead, we’ll replace it with an idea set forth by our friend Warren Sharp: a team’s tendency to throw the ball after an incompletion on 1st & 10. We’ll also tack on possession-and-10 (P & 10), which is just a fancy way of saying ‘the first play of a drive.’

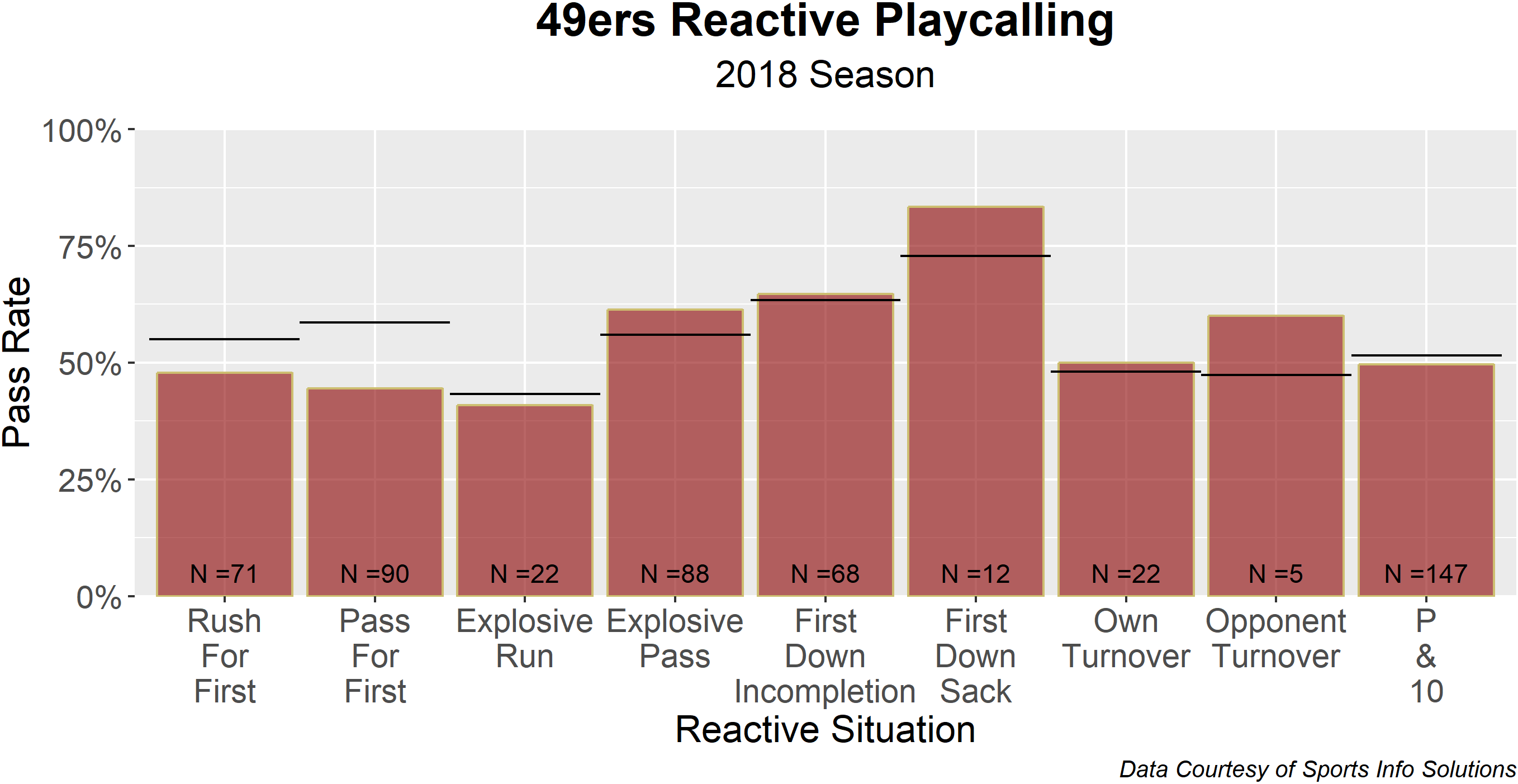

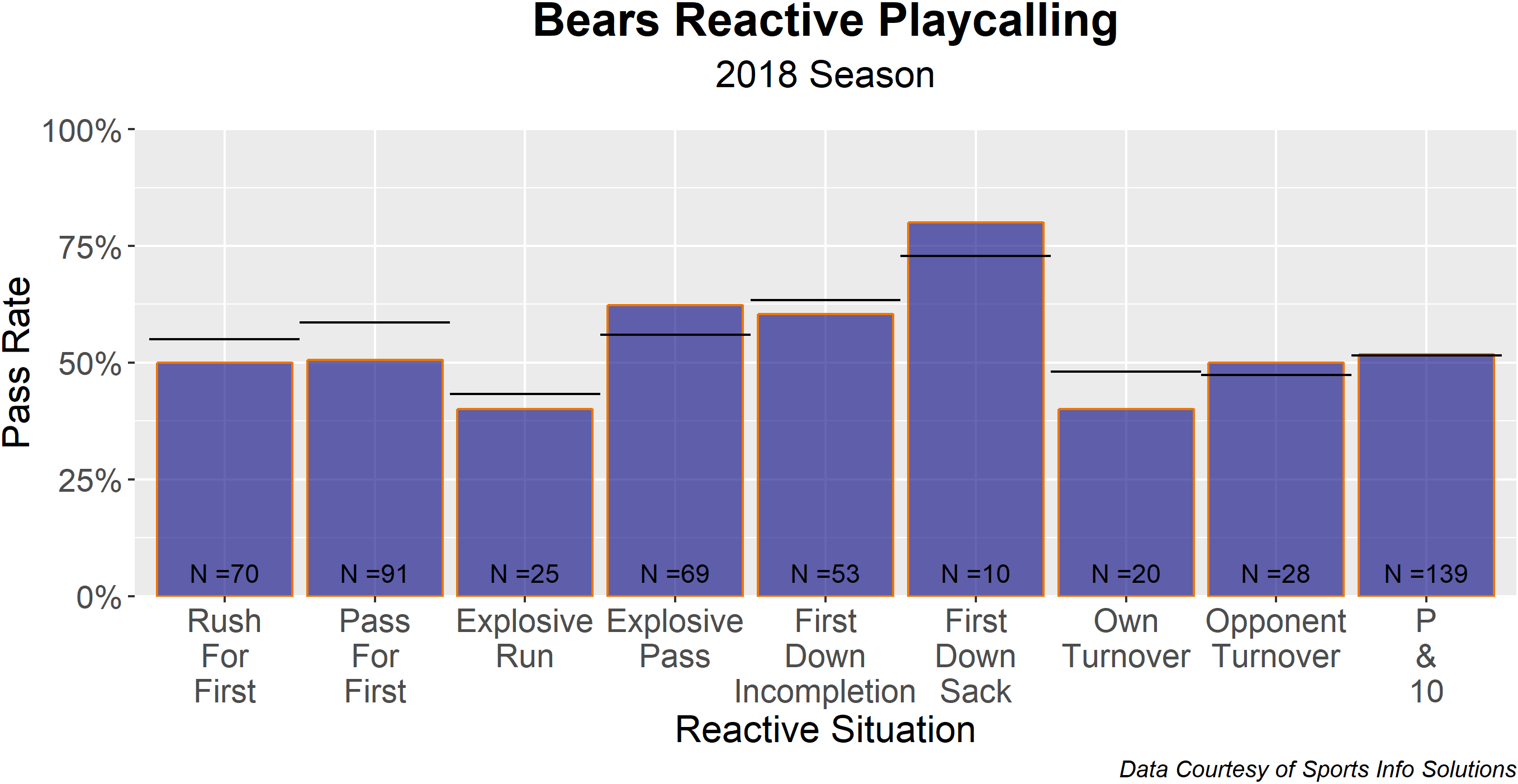

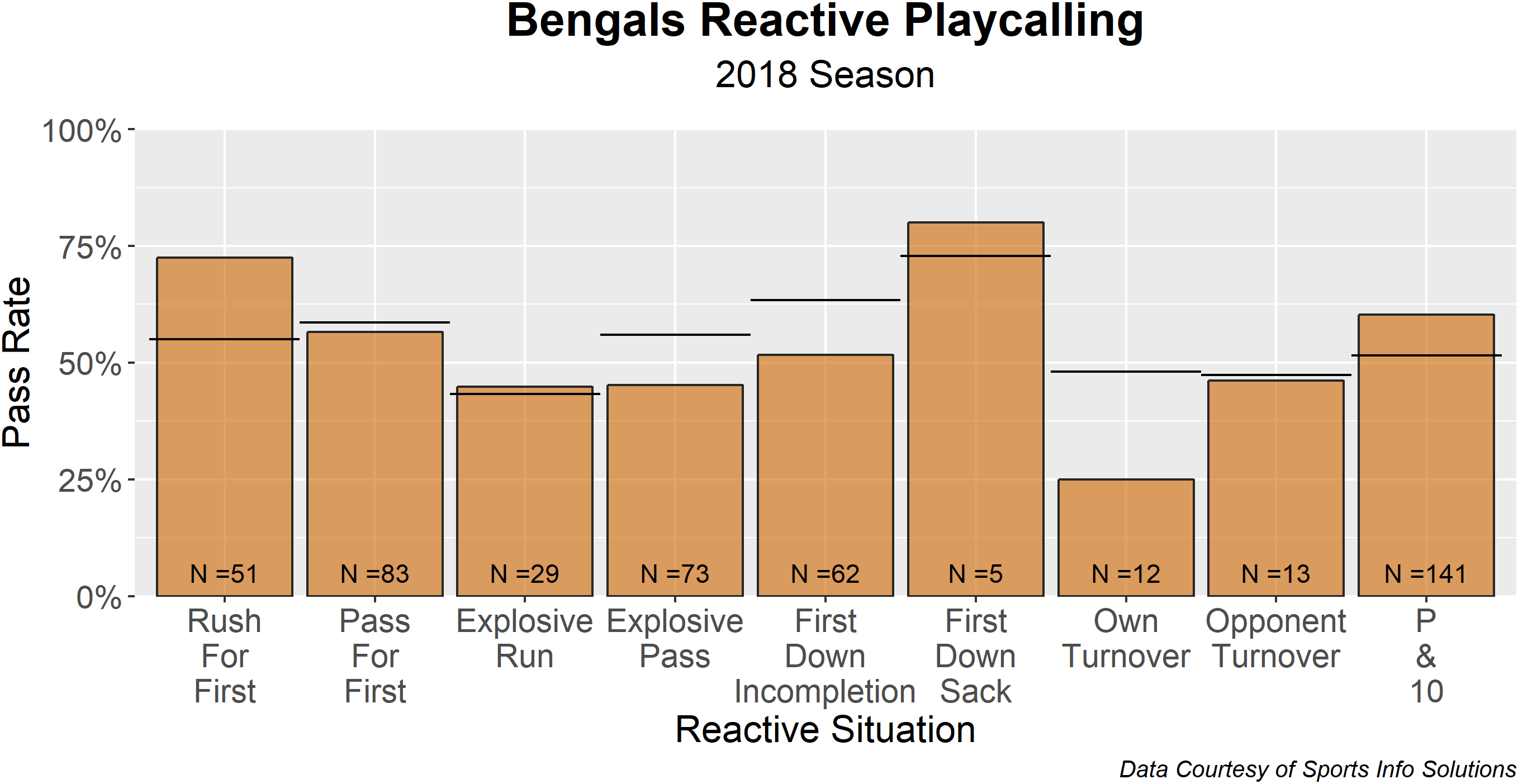

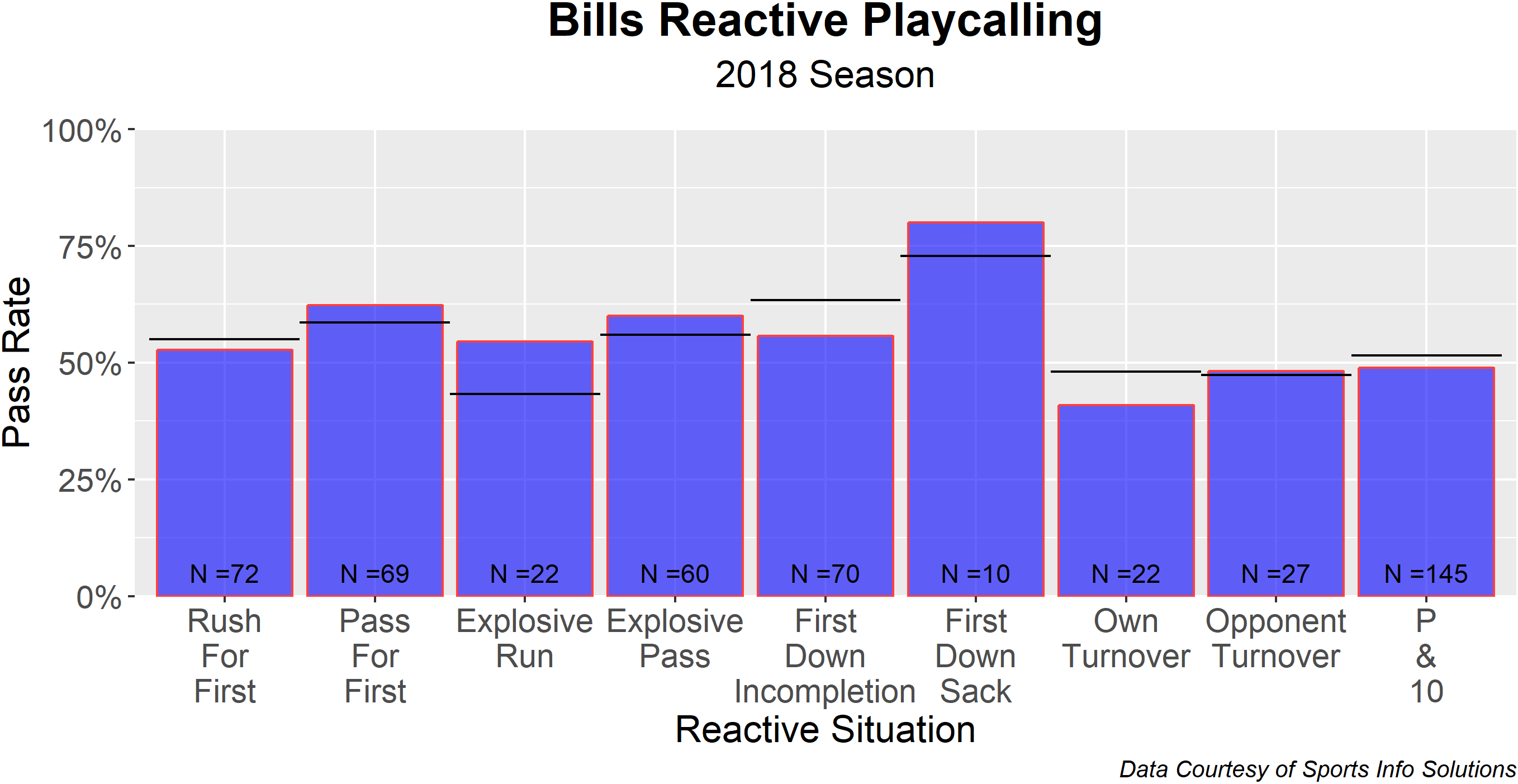

Rather than scribe out each team’s tendencies and waste your time with wordy prose and analysis you’re likely to skip over anyway, I’ve made something of a picture book. Below are 32 charts, one for each team’s reactive playcalling in 2018. But first, let’s go over some ground rules before we get started.

The black lines represent the league average rate for each reactive situation. “N =” indicates the number of times a team found itself in the specified reactive situation. Quarterback kneels were removed from the sample, so a team that kneeled the ball after hitting an explosive run to seal the game won’t have its pass rate watered down by such plays.

It should also be noted that explosive (15+ yards) passes and runs weren’t double-counted in passes and runs for firsts respectively, just as turnover-related opening plays are excluded from the P & 10 sample. Lastly, pass rate is based on the intent of the play, so scrambles and backwards passes are considered passes for the purpose of these calculations.

Without further ado, please enjoy and watch your step for small samples!