Baseball Info Solutions recently introduced a major update to Defensive Runs Saved that will be rolling out this offseason. We’re splitting DRS for infielders into Positioning, Air, Range, and Throwing components.

In that introductory blog post, we mostly covered how this will affect the Positioning and Range components (which were previously reported together as one “Range & Positioning” metric). However, it’s also important to note how this system can estimate the value an infielder adds with his arm.

So how do we calculate the Throwing component of the improved DRS?

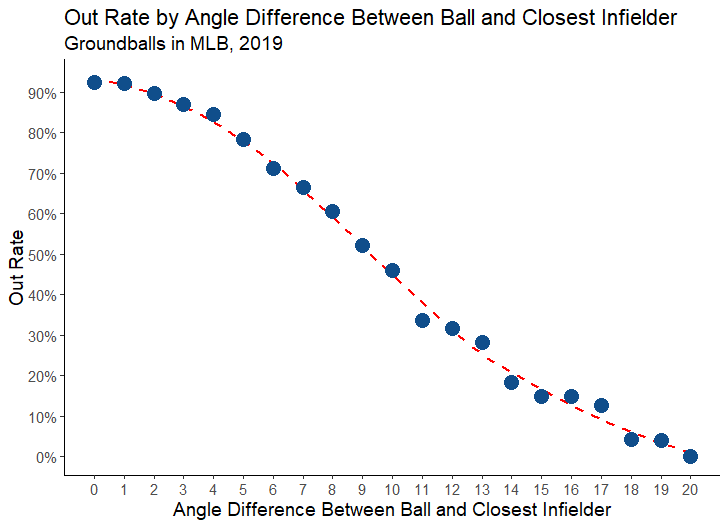

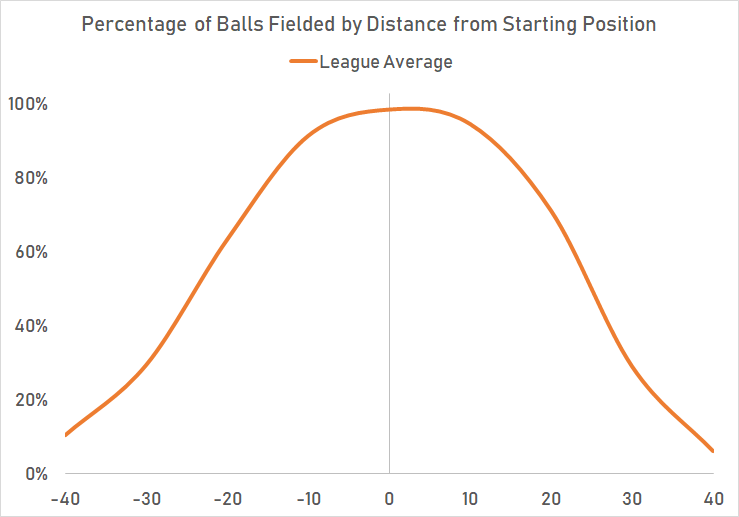

Using ball in play and positioning data charted by BIS Video Scouts, we estimate the chance that the play will be made at the point that the fielder obtains the ball, given the distance he must throw and how long he has to complete the play before the batter/runner reaches safely.

This number is then subtracted from whether the play is made (0 or 1). That value gives us how many plays were saved by throwing, which is then multiplied by an expected run value to generate runs saved.

Consider this play by Javier Baez. The chance that he would make the play from the point at which he obtained the ball – given his distance from first base and time to make the play – is estimated at approximately 39 percent. Baez made the play, so he’s credited with 0.61 plays saved (1 – 0.39).

Baez is a standout with his strong throwing arm at shortstop. With our new methodology, he tied Matt Chapman at +11 Throwing Runs Saved to lead all infielders in 2019.

Here’s a look at the top ten:

Throwing Runs Saved Leaders, 2019

| Player | Position | Runs Saved |

| Javier Baez | SS | 11 |

| Matt Chapman | 3B | 11 |

| Yolmer Sanchez | 2B | 8 |

| Amed Rosario | SS | 7 |

| Andrelton Simmons | SS | 7 |

| Jonathan Schoop | 2B | 7 |

| Nick Ahmed | SS | 7 |

| Tim Anderson | SS | 7 |

| Carlos Correa | SS | 6 |

| Kyle Seager | 3B | 6 |

Over the past three seasons, the leaders are Nick Ahmed (+23), Kyle Seager (+23), Matt Chapman (+23), Jean Segura (+17), and Yolmer Sanchez (+17).

This update to DRS allows us to not only split out the Positioning and Range components, but also to better understand an infielder’s value added with his arm. The data is now available on FieldingBible.com and will be featured in The Fielding Bible – Volume V (coming in the spring of 2020).

Stay tuned for more information and updates regarding this improvement to DRS.